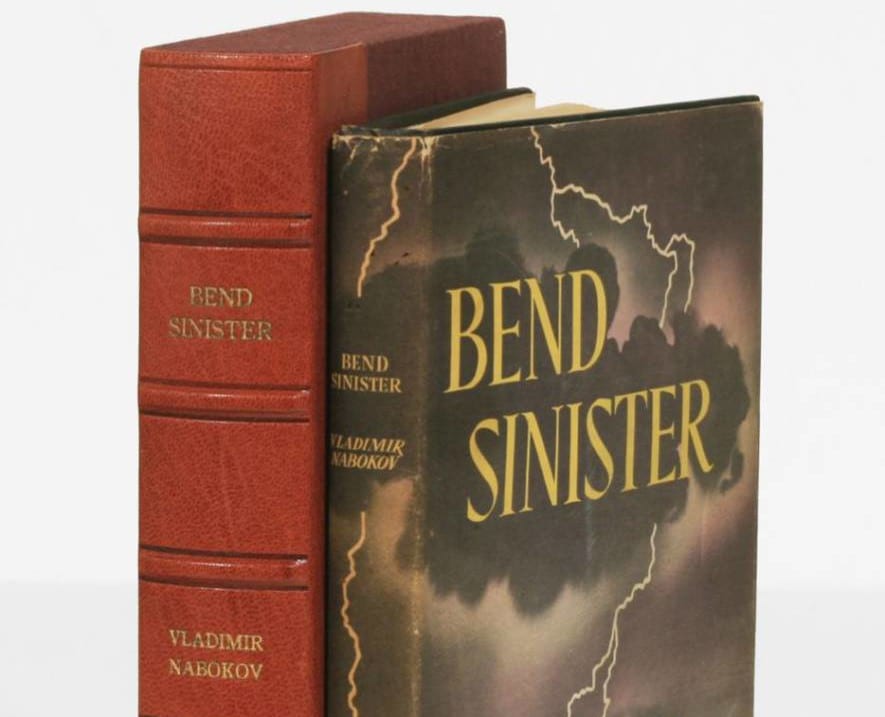

“Bend Sinister” by Vladimir Nabokov

Vintage, 1990. 272 pages.

If you’ve read Nabokov, you know that the story itself is almost entirely beside the point. Like sitting zazen, the reason to read Nabokov is to read Nabokov. Most people who’ve read Nabokov have read “Lolita,” and for a good reason. It’s one of the most brilliant collections of words in the English language ever to be assembled.

But eight years prior to writing “Lolita,” he wrote the lesser-known “Bend Sinister,” which delivers the same luminous verbiage with the same razor wit.

Just as Maurice Ravel was irritated by the public’s frothing admiration of his “Bolero,” which was for him merely a simple exercise in orchestration, Nabokov was very much annoyed by the critical acclaim his English received. He wrote in an epilogue to “Lolita,” “None of my American friends have read my Russian books and thus every appraisal on the strength of my English ones is bound to be out of focus. My private tragedy, which cannot, and indeed should not, be anybody’s concern, is that I had to abandon my natural idiom, my untrammeled, rich and infinitely docile Russian tongue for a second-rate brand of English. …”

Don’t let his modesty fool you. “Bend Sinister” is a lexicographic magic carpet ride.

But it’s not like, hey, wow, Nabokov used a bunch of big words. There are puns, anagrams, neologisms, spoonerisms, and cross-lingual Russian-English wordplay galore—and to hilarious ends. Reading Nabokov’s prose is similar to watching a virtuoso pianist improvise an extended cadenza in a concerto. It’s awe-inspiring.

He suffered from (or one might say that he enjoyed) synesthesia. The joke about smelling the number blue is real for a synesthete, whose senses are cross-wired. As a result, “Bend Sinister,” presents surreal Nabokovian passages, like “… Krug mentioned once that the word ‘loyalty’ phonetically and visually reminded him of a golden fork lying in the sun on a smooth spread of pale yellow silk. …”

The story itself is about Adam Krug, a philosopher living in the fictional European city of Padukgrad, near Omigod. The city is named after Paduk, the ruler of the city who came to power when a philosophy called Ekwilism (which no doubt means to imply, phonetically, “Equalism”) became fashionable. Ekwilism disparages people being different from one another, and Paduk guaranteed his success when he founded the Party of the Average Man. The society of Padukgrad, consequently, has dystopian elements and suggestive Orwellian overtones, but it’s far less calculating and frankly, stupider than any society illustrated by Huxley or Orwell—and much, much funnier. For example, Krug referred to Paduk himself, when they were in elementary school together, as “the Toad” and used to sit on his face.

The plot of “Bend Sinister” should remain a mystery for the benefit of any interested reader. Suffice to say that Krug struggles against a rising tide of mental mediocrity, which ultimately swells to tsunami-like proportions. But one of the primary themes is the idiocy of this society and how clumsily it carries out its Ekwilist motives—to ultimately ironic and even fatal ends. Krug makes the perfect foil for an entourage of lackeys, bootlickers, and thugs with more bravado than brains.

Even the intellectuals are self-spoofing, though. See the opening of “Bend Sinister,” wherein Krug is surrounded by his university colleagues, who prove to be shallow, pompous, and vapid. Or read Chapter Three, wherein Ember, a fellow intellectual and scholar of Shakespeare, tramples a variety of masterpieces with his hamfisted academic musings, including “Hamlet.”

Nabokov’s skill in weaving motifs throughout his work borders upon that of Beethoven. Most of them are so obscure that even the most attentive reader won’t notice them. Fortunately, many of them are pointed out in the introduction, but this mostly serves to impress the reader with the level of detail that Nabokov employs. However, he more obviously uses the motif of a puddle throughout the novel. Krug’s wife dies in surgery early in the story, and as he gazes out the window, the puddle makes its first appearance and reappears throughout the book as an inkblot, an inkstain, spilled milk, a footprint, and finally as the space left behind by a vacating soul.

Considering that Nabokov’s “day job” was that of an entomologist makes the staggering display of verbal acrobatics seen in “Bend Sinister” all the more sickening. If you read “Lolita” and were floored by his exhibitionist prose, check out “Bend Sinister.”