A few weeks ago at a friend’s wedding reception, I overheard a group of people talking about the recent bathroom legislation passed down from President Obama. While they admitted to each other that they didn’t know anyone who was transgender, they were adamant that anyone who didn’t fit into our culture’s neatly labeled and easily categorized gender binary had to be a pervert, an evil soul sent to corrupt the world and molest children in public restrooms.

A few weeks ago at a friend’s wedding reception, I overheard a group of people talking about the recent bathroom legislation passed down from President Obama. While they admitted to each other that they didn’t know anyone who was transgender, they were adamant that anyone who didn’t fit into our culture’s neatly labeled and easily categorized gender binary had to be a pervert, an evil soul sent to corrupt the world and molest children in public restrooms.

My first impulse was to put this group into my own neatly labeled box for bigots and hatemongers, crotchety conservatives who’d rather make others’ lives difficult than examine their own. But that’s not who they are. They are loving parents and kind neighbors who happen to have some extremely bigoted and outdated world views. It would have been easier to lump them all into that box, but it also wouldn’t have been true.

Over the course of human history, we have inched toward understanding ourselves as a species. As researchers press forward in fields like neurology, psychology, and even immunology, our picture of who we are as human beings begins to become clearer. Likewise, over the course of our lives, most of us come to understand ourselves better as unique individuals. Through analyzing our actions and reactions (consciously or subconsciously) and experiencing our highs and lows — what truly makes us happy or upset — we start to recognize our self-image a little better. And we want that. We want to look in the mirror and recognize the person looking back at us. When someone tries to slap a label on us, we become upset and defensive. We want them to see us for who we really are, not who they imagine us to be.

Over the course of human history, we have inched toward understanding ourselves as a species. As researchers press forward in fields like neurology, psychology, and even immunology, our picture of who we are as human beings begins to become clearer. Likewise, over the course of our lives, most of us come to understand ourselves better as unique individuals. Through analyzing our actions and reactions (consciously or subconsciously) and experiencing our highs and lows — what truly makes us happy or upset — we start to recognize our self-image a little better. And we want that. We want to look in the mirror and recognize the person looking back at us. When someone tries to slap a label on us, we become upset and defensive. We want them to see us for who we really are, not who they imagine us to be.

In direct conflict with this journey of self-discovery, it would seem, is our inherent desire to simplify things. We live in a big, complex world. When we encounter something for the first time, we like to categorize it, stick a convenient label on it, and move on with things — one more variable simplified to better help us deal with the complex reality of existing. But nobody is simple enough to actually fit a given label, and the labels we impose on others are often based on our own deeply rooted prejudices and insecurities. The prom queen who seems to have it all locked down is dealing with her own demons. The crotchety old man across the street has reasons for hiding his sensitive side. The ex-Mormon from your home town didn’t leave the church just to have sex and drink cheap vodka. The co-worker who identifies as female despite having been born with a penis isn’t seeking attention or just trying to be different.

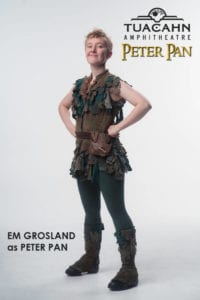

Em Grosland, who is playing Peter Pan at Tuacahn this summer, doesn’t fit into any of the boxes society has made for him as a transgender male. Sitting outside Perks Coffee House, Grosland walked me through his life, or as much of his life as one can cover in a Sunday afternoon conversation. Grosland pointed out that he didn’t feel trapped in the wrong body as a child (a common stereotype that even well-meaning people try to force onto transgender individuals). He didn’t always know he was transgender. He talked about growing up in Illinois with his loving and open-minded family, enjoying the mix of nature and city the area provided. He remembers his parents asking him and his sister to choose between a family vacation and performing in the upcoming dance recital each year because they couldn’t afford to do both. Smiling, Grosland noted, “Every year both my sister and I were like, hands down, dance recital.” He talked about the journey he took through dance and theater, the visual arts, and back to theater and how he didn’t love New York City when he first moved there but soon fell in love with Queens. It was the feeling of community amongst the artists that made the switch for him.

Em Grosland, who is playing Peter Pan at Tuacahn this summer, doesn’t fit into any of the boxes society has made for him as a transgender male. Sitting outside Perks Coffee House, Grosland walked me through his life, or as much of his life as one can cover in a Sunday afternoon conversation. Grosland pointed out that he didn’t feel trapped in the wrong body as a child (a common stereotype that even well-meaning people try to force onto transgender individuals). He didn’t always know he was transgender. He talked about growing up in Illinois with his loving and open-minded family, enjoying the mix of nature and city the area provided. He remembers his parents asking him and his sister to choose between a family vacation and performing in the upcoming dance recital each year because they couldn’t afford to do both. Smiling, Grosland noted, “Every year both my sister and I were like, hands down, dance recital.” He talked about the journey he took through dance and theater, the visual arts, and back to theater and how he didn’t love New York City when he first moved there but soon fell in love with Queens. It was the feeling of community amongst the artists that made the switch for him.

First, Grosland recognized his attraction to women and identified as a female lesbian. As he continued to try to better understand himself, the terminology he used to describe that self evolved too.

“I identified as pangender for a brief period of time and then found ‘transgender’ as a term to really be more accurate,” he explained. “I now identify as a trans male, but I also identify as non-binary because I think that our binary is detrimental to everyone, not just trans people. I think that there is a huge middle ground of gender and outside, even, of the spectrum that we’re not allowed to explore.” This recognition of the complexity of individual identity is important.

I identify as a straight, white, cisgender male. Still, as Grosland pointed out, “our binary is detrimental to everyone.” If I were to listen to what society tells me I should be as a man, I would probably be a much bigger asshole than I already am. But I don’t, or at least I try not to. While I am completely comfortable in my male identity, I gladly acknowledge that many of my personality traits are more commonly attributed to women. We are DNA built upon and borrowed from generations and generations of others’ DNA. I am in part my mother, in part my father. I am in part my grandfathers, in part my grandmothers. Grosland touched on this idea when he explained further.

“It was hard for me to let go of the female side of my gender, and I still haven’t completely because I’m a feminist and I was raised female, and I’m still perceived as female by most of the world. I don’t want to run away from that. I don’t want to let go of that because it’s part of my history. And not all trans people feel that way. Everybody has their own unique journey. I personally love my history. There are things that are painful about having been thought of as female and being seen as female my whole life, but I also feel like I gained certain things from that. I’ve been allowed a certain range of emotions by society that I feel like men are not allowed. And I really appreciate that a lot.”

Just like anyone living with a socially imposed label, no two stories are the same, and none of them perfectly fit into the corners of that box. In talking with my friend Roman, also a transgender male, the differences between his story and Grosland’s quickly became apparent. Roman grew up in the Midwest. He moved to St. George in his twenties to work as a counselor at an outdoor therapy program. Not a member of the LDS church, Roman felt the culture shock so many do when they move to Utah, but he stayed because of his love for the land and ended up finding a tight-knit LGBT-friendly community. At the time, Roman identified, both to himself and others, as queer, a move at least one side of his family supported.

It was a girlfriend he had in St. George who first raised the question of his gender identity — sadly with the caveat that she didn’t want to be with a man. “That wasn’t a bad thing for her to say. She was being honest, and she wanted me to explore that and just be honest with myself,” Roman noted.

Somewhere in Roman’s mind were memories of identifying as a boy when he was a child, even trying to convince his classmates of it, changing his name on his homework to Mike, passing any test other boys gave to him like running laps, peeing in a urinal, and eating a cicada shell. But nothing worked. “It was just shut down so much that I put it away.” In fact, Roman would later be surprised how deeply he’d buried it.

Visiting with me over the phone late one night, Roman admitted, “I’d been a bit transphobic to be honest, before coming to that realization. And I’ve found throughout my life, anytime that I’m adamantly fighting something in someone else that just doesn’t make sense, it’s because it’s part of the mirror I don’t want to look at, and I’m seeing it in them.”

Acknowledging his male identity was frightening for Roman, as it is for so many. He was concerned with the effect it would have on his more conservative family members who’d just learned to accept that he was queer and embrace him (as a woman at the time) being with another woman. As he put it, “There’s just a bunch of different steps of grieving the false life that I had been accustomed to. It took me a while to wrap my head around.”

Discovering and accepting his gender identity as a transgender male certainly wasn’t the end of the road for Roman. He acknowledged that he still has struggles with depression and anxiety. Shortly after starting on testosterone Roman noticed that, “Living [his] authentic life is not the cure all for [his] problems.” But, having accepted that part of himself and moving down that path has given him solid footing from which to manage those other problems. As someone who manages his own clinical depression on a daily basis, I can appreciate the need for that footing.

Unlike Roman, my friend Lex grew up in St. George. And unlike Roman or Grosland, he had no period of doubt or questioning in regards to his gender identity. Though he’d been born female, Lex knew from early in life that he was a boy. In a primarily conservative, predominantly religious town, this often made him a target.

“Being a thirteen-year-old who knew he was transgender in St. George, it was quite the adventure,” said Lex. “Having friends who were Mormon and their parents were like, ‘No, you cannot have this friend who is not part of the church’ … it kind of fucked me up a little bit.” Due to peer pressure and some transphobic comments from his father, Lex eventually did succumb to hiding his identity, lying to himself and others every day about who he was. Lies only stay hidden for so long, and years later Lex made the decision to once again embrace his true identity as a transgender male.

As I talked with Lex about those years he spent hiding, his voice thinned with emotion, and he eventually had to step away for a moment to gather himself. The pain of living that lie hung in the air, and once again reminded me how brave it is for some people just to be who they are.

There are commonalities between their stories. Each of them fears using public bathrooms, a fear that is justifiable when you look at the rate of violence against transgender individuals (as opposed to the unjustified, politically motivated fear that transgender people are using bathrooms to molest children). All three of them mark an internal feeling of joy, almost unexplainable at the time, at being seen as a man as a turning point or a marker of sorts in their exploration of self. The first time Lex bought clothes from the men’s department, the time a teacher called Grosland a boy before he’d even self-identified as a man, every time a stranger uses the correct pronoun to address Roman … these are the deeply rooted emotional proof of their identity.

As each of them told me about these moments, I felt something I’ve felt often before. It’s a depth of sincerity and nostalgia. The same kind that I’ve felt from people sharing their religious conversion stories with me or their moment they knew, inexplicably, completely, that they were in love. I have felt this in myself a precious handful of times, and each of them led to a breakthrough in self-discovery. These are the temples we decorate inside of ourselves.

These men, these good men, are examples not only to the LGBT community — to the young trans boys and girls who need to see that there is a way to be themselves and be happy — but to everyone of having the bravery to explore and continue to learn about who we really are.

NOTE: My deepest regret with this article is that the three men I interviewed for it are too complex and have too much depth as individuals and inspiring stories and details from their lives for me to do them any real justice here.

Thank you Darren. I appreciate what you are doing for our community – giving voice to those who may be misunderstood without placing blame or pointing fingers. I especially appreciate that the focus is on identity and how unique that is to each of us, instead of pushing a political agenda or religious perspective.

That’s very kind of you to say. Thank you, Sara!