https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KhJ9IwYc5NU

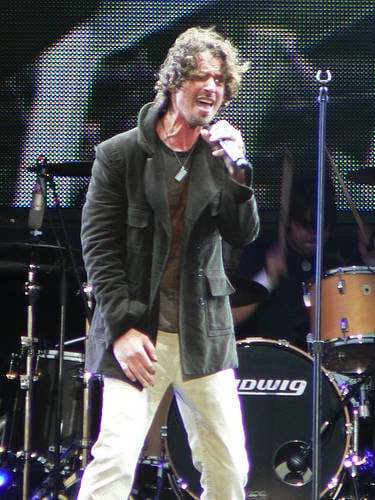

Album Review: Chris Cornell’s “Higher Truth”

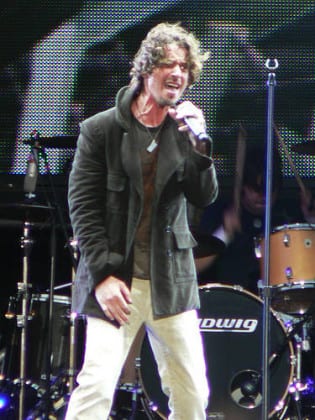

![]() How many frontmen and frontwomen have ditched their bands or walked away from a messy breakup, only to rise from the ashes stronger than ever? Where to start? Eric Clapton, Bjork, and all three Beatles pulled it off. Robert Plant did it. Don Henley did it. Sting did it. Chris Cornell hasn’t turned his back on Soundgarden, but he’s thoroughly demonstrated with “Higher Truth” that musically, he’s his own man.

How many frontmen and frontwomen have ditched their bands or walked away from a messy breakup, only to rise from the ashes stronger than ever? Where to start? Eric Clapton, Bjork, and all three Beatles pulled it off. Robert Plant did it. Don Henley did it. Sting did it. Chris Cornell hasn’t turned his back on Soundgarden, but he’s thoroughly demonstrated with “Higher Truth” that musically, he’s his own man.

Chris Cornell fronted two “supergroups,” Temple of the Dog (alongside Pearl Jammer Eddie Vedder) and Audioslave, which began as a Soundgarden-Rage Against the Machine hybrid. More famously, he fronted Soundgarden, one of the bands at the vanguard of the Seattle grunge scene of yore. To be frank, Cornell and a handful of other musicians were the ‘90s. As far as grunge goes—and its more long-lived current manifestations as alternative rock or post-punk—Kurt Cobain was the Father, Eddie Vedder is the Son, and Chris Cornell is the Holy Spirit. (Does that make Sub Pop’s Bruce Pavitt the Pope?)

Soundgarden is still kicking, so Cornell is able to make as much noise as he wants to there. What is so refreshing about Chris Cornell’s new album, “Higher Truth,” is that it is decidedly not Soundgarden 2.0. It doesn’t even begin to try. It ain’t the ‘90s, and pretending that it is has proven to be a tricky endeavor for some. Veruca Salt pulled it off earlier this year, but the results were lackluster if successful. To do the same would have been dangerous for Cornell. After all, carob chips may be delicious, but they just aren’t chocolate, are they?

“Higher Truth” truly is a solo album, a separate side project rather than a deluded attempt to relive the wonder years. Not that he is really the type to rest on his laurels or switch gears to cater to the public for the sake of commercial success. In 1994, he told Rolling Stone interviewer Alec Foege that “A couple of years ago I ran into a friend of mine from high school, and he said, ‘Wow, I’m so glad you made it.’ I shook his hand and said thanks. Then I started thinking, ‘What the fuck does that mean — “made it”?’ Does that mean I can just go home and pick my feet up and make as many long-distance phone calls as I want? Can I be rude to all my friends and they’ll still love me in the morning?’ It doesn’t make any sense to me.”

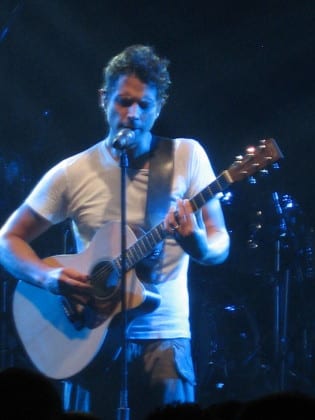

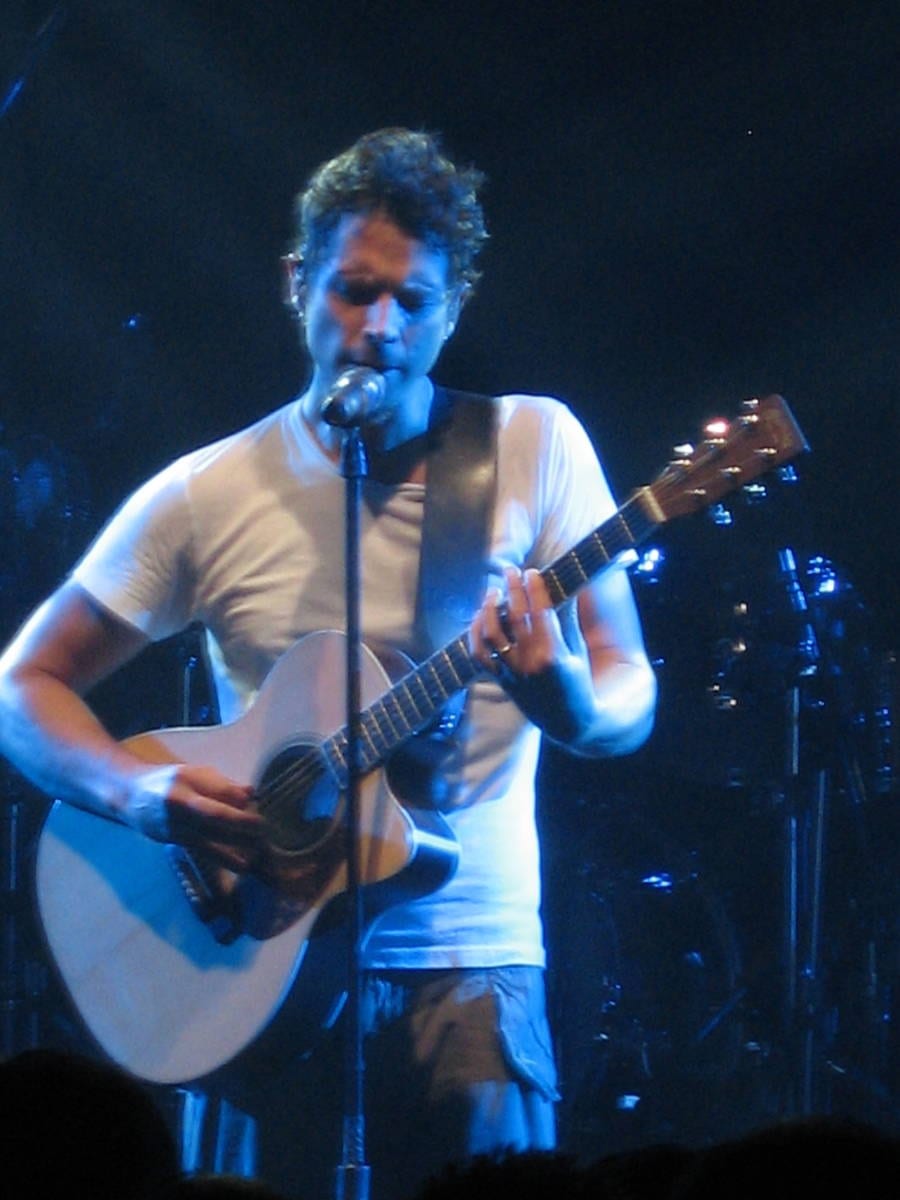

Rather, Cornell has recorded something genuine. He’s singing as well as ever, and Brennen O’Brien (a producer who has worked with everyone) has brought these songs to life rather than trample them with bells and whistles. The approach isn’t exactly minimalist, but it’s a far cry from the blaze of Soundgarden or Audioslave. There’s a heavy acoustic element, but more marked is the (purposeful) lack of a “band” sound. Matt Chamberlain does show up on drums occasionally, but for the most part, it’s Cornell and O’Brien just piecing something together casually song by song. In fact, the album is almost entirely Cornell and O’Brien playing everything. If the album has a fault, it’s that it does at times sound a bit like a home studio demo. But if that’s the case, it’s certainly among the best home studio demos ever recorded, up there with the likes of Django Django and Animal Collective.

Regardless of what you expected, “Nearly Forgot my Broken Heart” opens with mandolin and features some smooth bass playing—a consistent feature on this album—and a rich spread of background percussion, also a pervasive element on “Higher Truth.” Cornell began his musical life as a drummer, and the drums are tellingly groovy as hell without ever threatening to draw attention to the song but rather adding to it—as they should.

Similarly, “Dead Wishes” opens with some acoustic picking and maintains the feeling of a travel song, although it’s really more about regret:

Dead wishes on a burning lake

White roses from my soul to keep

Down and out with everything to win

If my long since sunken ship

Ever does come in

With some tasty playing across the board, some great vocal harmonies on Cornell’s part, and a perfect lyrical balance between understatement and overstatement having been struck, this song is hard to beat.

Not to minimize it, but “Worried Moon” is more of the same, which is a compliment. The modal borrowing in the chorus and an unresolved secondary dominant (although it does resolve when it leads into the bridge) make the chorus really pop, harmonically.

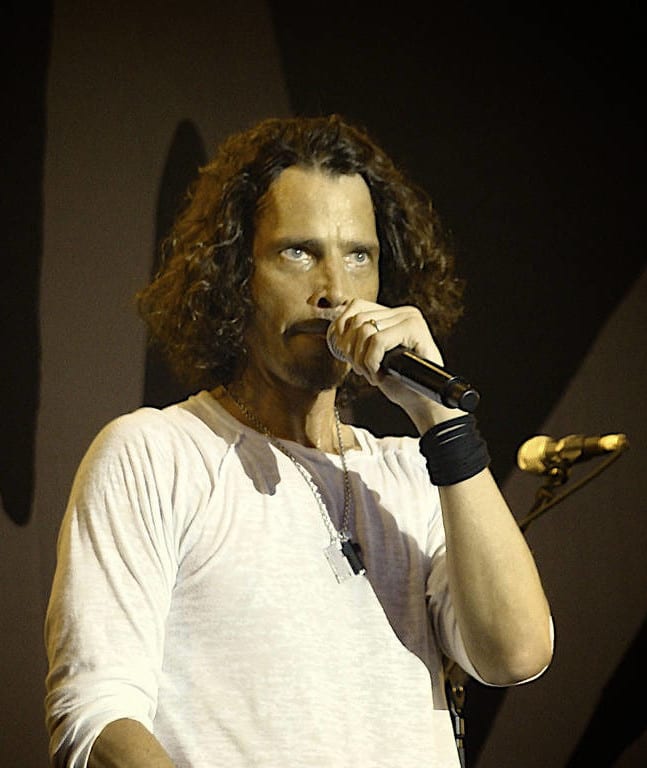

“Before We Disappear,” one of those “carpe diem” songs, laments that time and life are harsh. Accordingly, in “Through the Window,” Cornell’s voice is maybe a little more exposed, not that it’s ever buried. And it isn’t constantly doubled or chorused like ‘90s peer Scott Weiland’s always seems to be. The texture is really palpable, and it’s clear that just as with Peter Gabriel’s, his voice is aging well.

“Josephine” is just Cornell singing with a six-string to the accompaniment of chamber strings arranged by Ann Marie Simpson—an appropriate treatment of a marriage proposal song.

“Murderer of Blue Skies” has dark production. An old kit lays it down over Cornell’s picking as a low, growling bass steps in underneath. The chorus is one of those choruses that sounds like it wrote itself. As if he couldn’t resist, an electric guitar solo jumps in after the chorus. There’s not too much of that sort of thing on “Higher Truth,” and some of it is to be expected—it’s Chris Cornell for Pete’s sake.

The title track leaps around harmonically and departs from the guitar-based approach of the rest of the album. Rather, it’s piano driven, and between the four-on-the-floor piano pounding, the avoidance of typical pop harmonic cliches, the understated drumming, the organ accompaniment, and even some choral la-la-las, it almost sounds like Cornell found some obscure George Harrison tune and rerecorded it. It builds up and bleeds away more like something from early Radiohead; however, even that tendency itself is arguably another Beatles influence.

As if to cleanse the palate, “Let Your Eyes Wander” reverts to the singer-songwriter approach: just Cornell and an ambling guitar. The same is true of “Only These Words.” Although there is a little light accompaniment in the background on both tracks, they even out the wake of the title track as a pair of acoustic-based love songs.

“Circling” is probably the best-written song that’s the worst produced. It would have joined the previous two sings in a triptych if it weren’t for the blaring intrusion of an electric guitar and an overly vociferous bass part. It’s not enough to ruin the song so much as make it quirky.

Things end on a quirky note. “Our Time in the Universe” feels like “Black Hole Sun” lite. An oriental string motif punctuates the song—also quotes by Cornell’s six-string—which is otherwise the album’s fist-pumping stadium anthem. The production is the most adventurous here, and the album thereby goes out with a bang.

Cornell’s last solo album, “Scream,” which was bizarrely produced by Timbaland, received sharp criticism. And rightly so. Trent Reznor summarized it for the whole industry with a biting tweet: “You know that feeling you get when somebody embarrasses themselves so badly YOU feel uncomfortable? Heard Chris Cornell’s record? Jesus.” With “Higher Truth,” Chris Cornell has totally redeemed himself. Even longtime fans may be surprised that he had something like this in him. If you haven’t touched your six-string in a while, “Higher Truth” will compel you to pick it up. If you haven’t written a lyric or a poem in a while, “Higher Truth” will nudge you toward your desk. If you’re thinking about what album to buy next, you could do worse than “Higher Truth.”