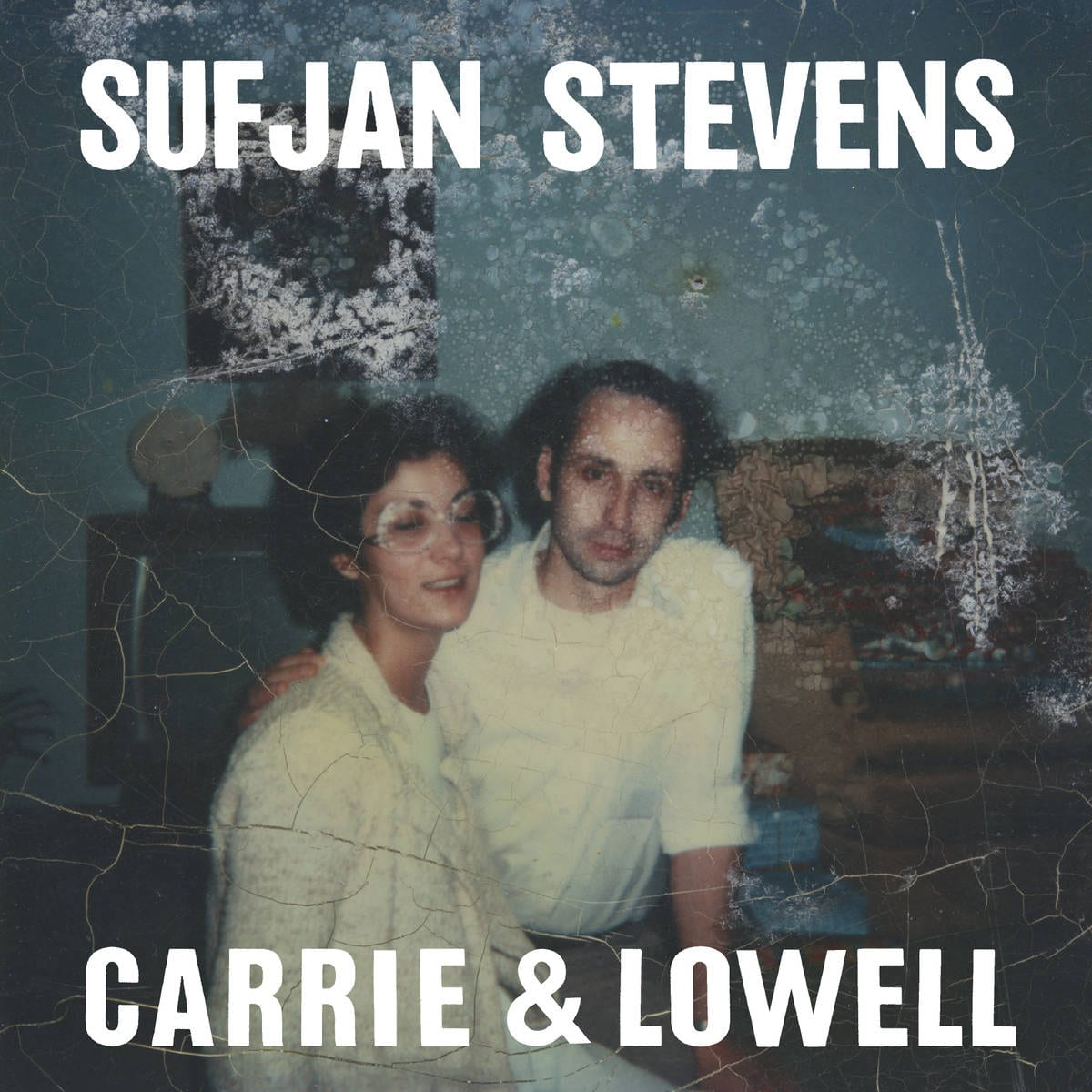

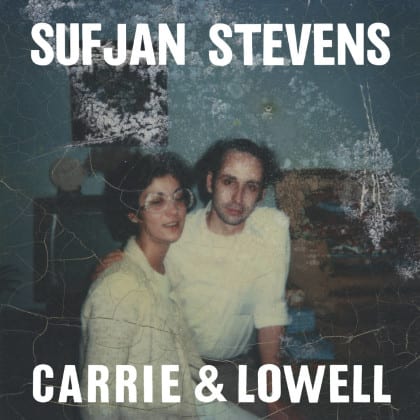

Album Review: Sufjan Stevens’s ‘Carrie & Lowell’

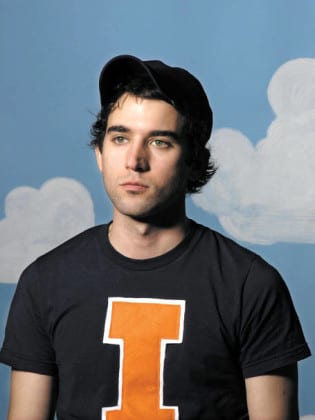

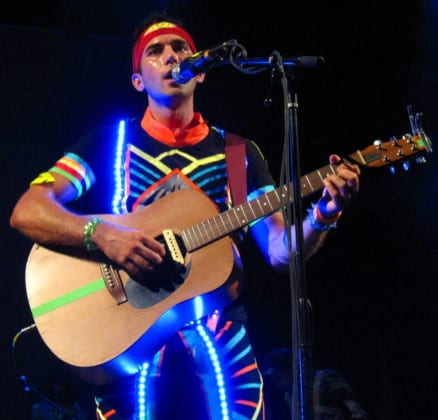

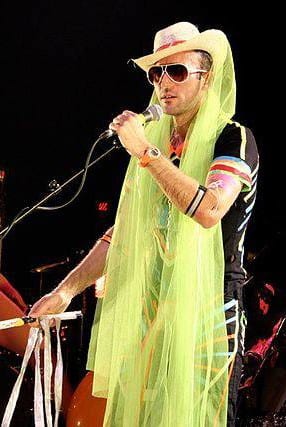

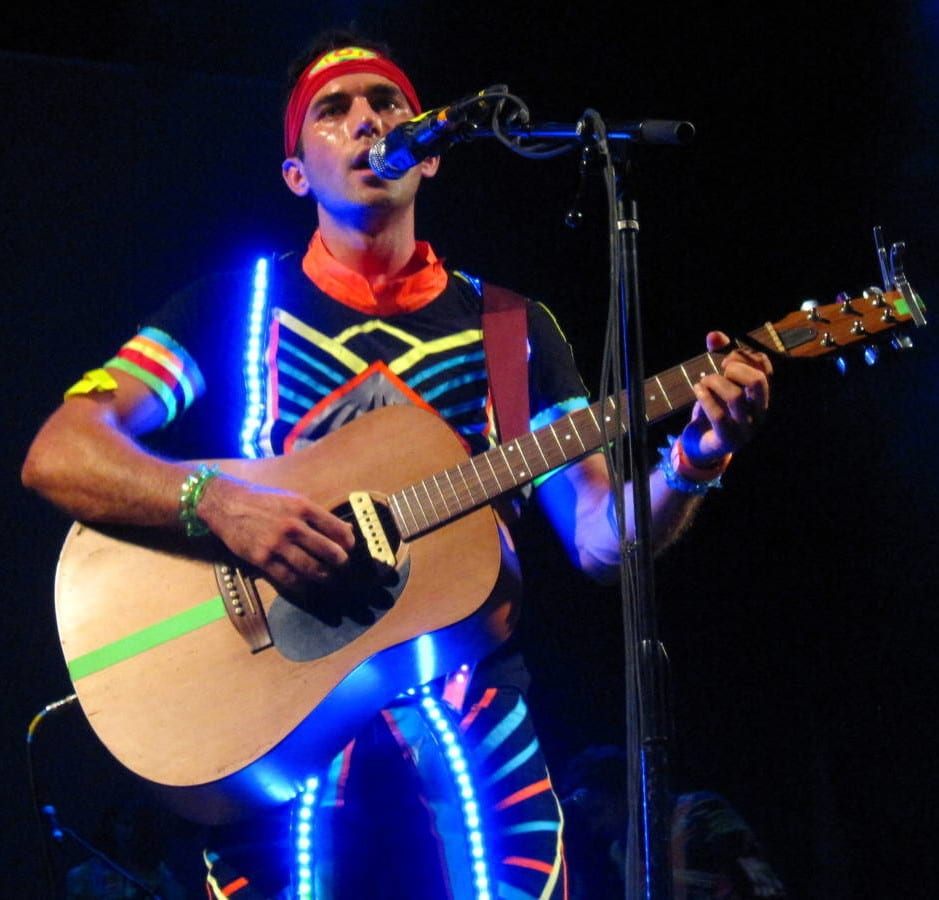

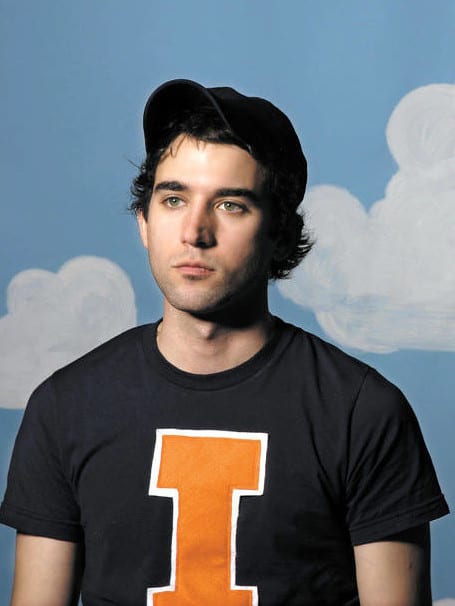

No one has really had the balls to so boldly straddle both the contemporary Christian and secular pop-rock genres like Sufjan Stevens has since Jars Of Clay. Some major pop stars—like Sting, Seal, and Madonna—have alluded to their faith musically, although it’s hard to imagine Madonna taking the stage at Fishfest. And others like Amy Grant have tried with nominal success to walk the same tightrope that Stevens has navigated for some time. But Stevens has comfortably integrated religious themes consistently enough to be considered a hybrid secular and religious songwriter. With Jason Mraz, he has been one of the longstanding pretty boys of the indie scene, and often we’re not sure how seriously we can take him until we actually listen, at which point he seems like a young, sheepish James Taylor.

Few singer-songwriters have the sincerity and poetic maturity as Stevens. While “The Age Of Adz” was arguably a lackluster follow-up to the poignant majesty of “Illinois,” Stevens is back in his comfort zone with “Carrie & Lowell,” a tribute to the recent loss of his mother.

Standing tall in the footsteps of Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel, “Death with Dignity” begins with the kind of high-on-the-neck guitar picking for which Stevens is known and expresses a general sense of ambiguity and loss with the repetition of “I don’t know where to begin.”

“Should Have Known Better” continues similarly, with plaintive vocals and subtle harmony that descends in first inversion. Briefly, the perfect kind of guitar solo appears wherein every note is placed in exactly the right place, as with flower arranging. Banjo and very light keys enter, and the textures thicken slightly with a high, gentle ostinato. The song ends darkly, with ambient clouds of what could be a renaissance consort of viols.

The syncopated strums of autoharp and guitar carry “All Of Me Wants All Of You,” and agreeably synthy instrumentals make an appearance. Stevens’ unique guitar work on “Drawn To The Blood” blends the steady, rhythmic down-strum of Billy Corgan with Steve Reich’s subtle dynamic swells. Stevens pleads with the “God of Elijah,” imploring, “How did this happen?” This question gives way to sonorous swells.

Another simple folk song, “Eugene” demonstrates Stevens’ seemingly effortless comfort with the folk genre, almost evoking The Beatles’ “Blackbird.” A dark, steady piano introduces “Fourth Of July,” in which he attempts to communicate with his mother:

To wrap you up in cloth

Do you find it alright, my dragonfly?

He ends with a bleak but insistent acceptance that “We’re all gonna die.”

Strongly referencing Sophocles, “The Only Thing” ventures into Greek mythology with a series of visual vignettes behind a relaxed backdrop of expert fingerpicking. The title track follows, bringing us back to the transparent intimacy of “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.”

In “John My Beloved,” Stevens continues to explore the impermanence of life, taking some comfort in “No Shade In The Shadow Of The Cross.” “Blue Bucket Of Gold” is nearly whispered over a muted piano and eventually floats away, ghostly and uncertain.

One could argue that it’s unfair to compare anything Sufjan Stevens releases to career highlights like “Illinois.” It would be equally unfair, however, to assume that he’s peaked. “Carrie & Lowell” feels like a necessary return home for Stevens. It’s an expression of mourning, and as such it’s perhaps a little self-indulgently singer-songwritery. But at least Stevens has left the electronic landscape of “The Age Of Adz” for the more hospitable climes of indie folk, where—as usual—he shines.