Utah Shakespeare Festival’s “An Iliad” is a powerful rumination on the nature of war

Brian Vaughn has been a fixture at the Utah Shakespeare Festival for more than two decades. He’s starred in some of the festival’s biggest plays and most memorable roles. Yet his performance in “An Iliad” may be his best yet.

Vaughn is on stage for 100 minutes and is speaking nearly the entire time. Even for seasoned actors like him, that is a challenge. Not only does it require a whole lot of line memorization but it must be delivered in a dynamic way that manages to maintain the audience’s attention without the advantage of the interactions that come with a larger cast.

Yet Vaughn seems entirely at ease in the role of The Poet, a modern storyteller who might actually be Homer himself. He enters the Eileen and Allen Anes Studio Theatre silently, walking around the stage — which is surrounded by the audience on three sides — as if he’s gathering energy to launch into this epic story.

It’s pin-drop silent.

Ever the charismatic presence, Vaughn manages to hold the audience in rapt attention, even through that initial silence. Finally, he speaks, announcing that he is about to tell the story of the Trojan War and two great fighters, Achilles and Hector.

The basic storyline is based on Robert Fagles’s translation of Homer’s epic poem, “The Iliad,” but the words were written by playwrights Lisa Peterson and Denis O’Hare. The script allows The Poet to bring in contemporary references, connecting the Trojan War to modern scenarios, from grocery-store lines to road rage.

the playwrights want us to do more than simply relate to the events of the Trojan War. They want us to know that war is hell.

This approach makes the events more relatable. However, the playwrights want us to do more than simply relate to the events of the Trojan War. They want us to understand the nature and magnitude of war in general. They want us to know that war is hell.

Rather than noting the Greek island towns of origin for the soldiers in Achilles’ army, The Poet brings it home to an American audience. He says these are soldiers from Kansas, the Bronx, Flint, and Cedar City. Then he begins to count. The numbers aren’t soldiers. The numbers represent ships. And each ship has 120 men. We begin to grasp a magnitude of human life in this particular conflict.

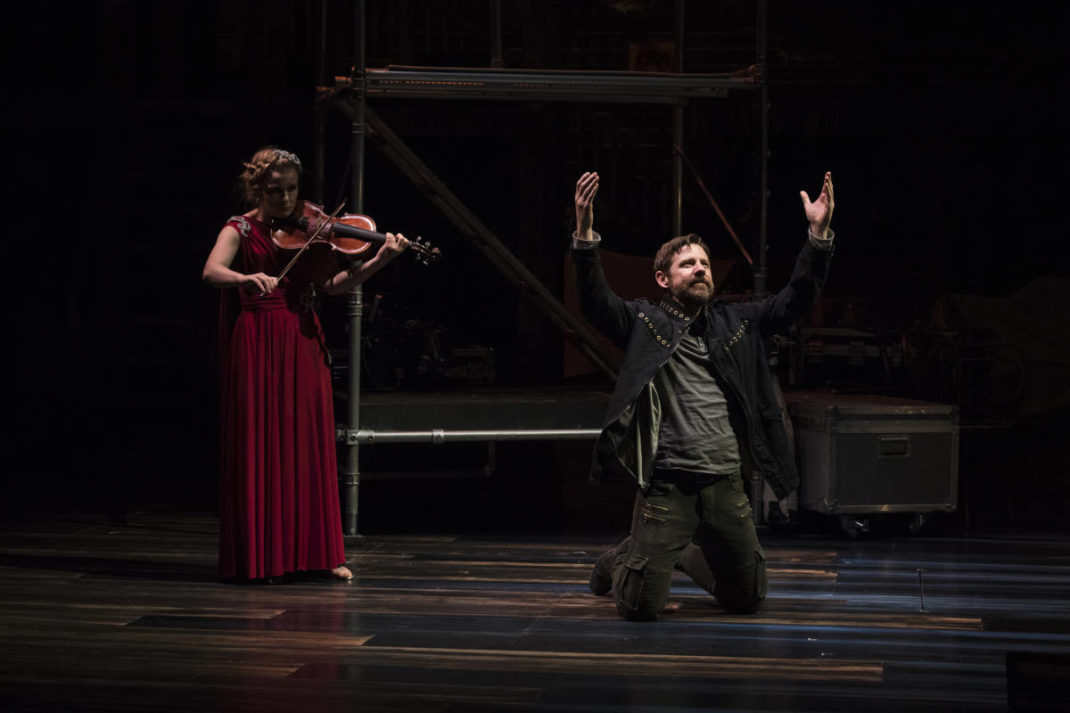

While Vaughn tackles the vast majority of dialogue, he’s only alone on stage at the beginning. Shortly, he’s joined by Katie Fay Francis (who touchingly portrayed Catherine Simms in “The Foreigner” this year) as The Muse. Her role is primarily musical as she sings and plays the violin, though she does have a few lines.

Francis’ role may seem minor compared to Vaughn, but her melodies and percussion bring a dynamic jolt to the play and Vaughn’s own performance. At times, she simply keeps the beat, tapping out basic percussion on her instrument. At other points, her violin screams, enhancing the play’s drama with its intense trills.

Most striking is Francis’ voice. It’s often ethereal and always gorgeous. Her wordless vocals — combined with the percussion and violin melodies — create a soundtrack that enhances the play, similar to the way a film score helps tell the story. Some of the characters, from Apollo to Paris, even get their own theme music.

As Vaughn introduces the characters, the storyline begins to unfold. His voice rises at times and falls at others. He’s the consummate storyteller, building the drama when appropriate and then pulling back so he’s able to build it up again. Even though it’s a story of war, it’s not all about the fighting. There’s plenty of character development as The Poet paints a picture of Troy, its residents and its assailants.

This is a master class in storytelling.

Assisting in the storytelling is lighting designer William C. Kirkham. That might seem odd. Obviously, lighting often enhances the beauty and artistic qualities of a play, but we may not always think of it as an aspect of storytelling. With “An Iliad” it most definitely is.

Consider the part where The Poet is talking about Hector’s family. The lighting is soft and warm as The Muse’s gentle melody sways in the background. The Poet then says he is going to describe the front line of the battle. Suddenly, the music stops as bright light abruptly calls our attention to a description of dead bodies.

Again, the playwrights brings this scene home. Instead of simply thinking of the fallen soldiers as a mass of nameless Greeks and Trojans, we get names, ages, and other details about their lives. But they aren’t Greek and Trojan names and details. No, they have American names and American stories.

It begins to become clear. This ultimately isn’t a story about the Trojan War. It’s a story about war and what it means to the human race. Wars are not just full of heroic moments that result in national boundary changes. Wars take the lives of real people — individuals with their own stories that suddenly cease to exist because of the politicians and monarchs they will never even meet.

“An Iliad” personifies the Trojan War. Its violence and fury come alive as Vaughn screams his lines, shouting above Francis’ careening violin under the blood-red lighting.

Perhaps most perplexing is how we feel for both sides. It’s because we see them all as human beings. They have wives and sons, mothers and fathers. They are also capable of horrible things, fueled by the adrenaline and fury of battle. War truly is hell.

Director Jason Spelbring pulls all of these elements together. Under his direction, each change in tone, volume, and illumination appears flawlessly executed. This is a master class in storytelling.

Yet we are constantly reminded that this is more than just a story. As The Poet begins to compare an element of the Trojan War to a different historical war, he keeps the comparison going, listing every major historical conflict in chronological order, including those meant to speak to an American audience: the American Revolution, the War of 1812, the American Civil War, World War I, World War II, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq.

War. War. War.

It seems to ask: Why do we continue, time after time throughout history, to kill each other?

Because we’re addicted to rage. All of us.

And that addiction leads to the destruction of civilizations, from Troy and Alexandria and Constantinople to Hiroshima and Kabul and Aleppo.

War is hell, but “An Iliad” is a masterpiece about the hell of war.

The Utah Shakespeare Festival’s production of “An Iliad” continues through Oct. 9 in the Eileen and Allen Anes Studio Theatre at Southern Utah University’s Beverley Center for the Arts in Cedar City. Tickets are $50–$54. Visit bard.org or call (800) 752-9849.

Articles related to “Utah Shakespeare Festival’s ‘An Iliad’ is a powerful rumination on the nature of war”

Utah Shakespeare Festival’s “Henry VI, Part One” is flawed, but Joan of Arc sizzles

Get your Falstaff on with “The Merry Wives of Windsor” at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Utah Shakespeare Festival’s “Big River” is delightful but sobering