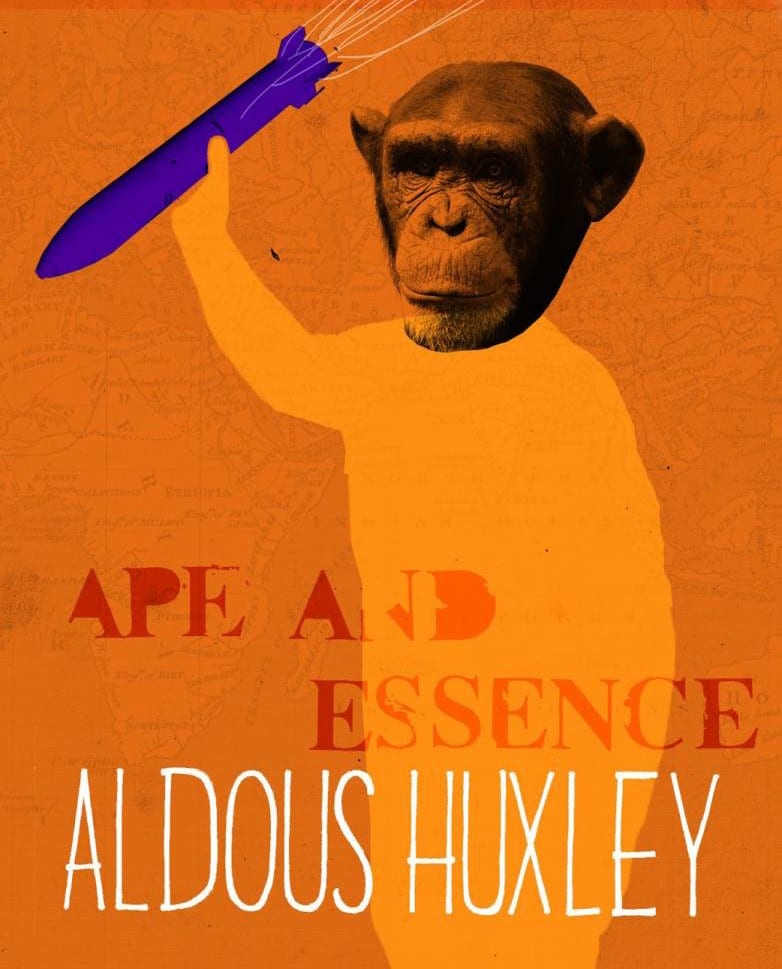

“Ape and Essence” by Aldous Huxley

Harper and Brothers, 1948, 152 pages.

Like much of Aldous Huxley’s writing, “Ape and Essence” blends satire and social criticism and bears the seeds of science fiction, as does “Brave New World” and “Island.” However, it is more disjointed than some of his more popular novels, like “Eyeless in Gaza,” and incomparably more surreal than “Point Counter Point” or “After Many A Summer Dies the Swan.”

“Ape and Essence” has a strange structure. It is comprised of three basic parts—one realistic, one fantastic, and one fictional—which only loosely relate to one another. The book is in two sections: “Tallis” and “Ape and Essence.” However, the second section of the book, which comprises well over three quarters of the novel, is a play that main characters Bob Briggs and Lou Lublin stumble upon entitled “Ape and Essence.” The play itself alternates between its own storyline and interjected vignettes wherein baboons emulate modern society.

“Ape and Essence” opens with Briggs and Lublin discussing Brigg’s affair on the day of Gandhi’s assassination. A truck full of movie scripts drives by, and when the screenplay “Ape and Essence” lands at their feet, they are intrigued after reading a page or so and set out to find the author, William Tallis, in Murcia, California.

They discover that Tallis is deceased when they visit his remote desert home—which fits the description of the house where Huxley himself lived while writing the novel. Having been denied a meeting with Tallis, Lublin reproduces the text of “Ape and Essence” in its entirety in the second section of the book.

The screenplay itself, while set in the post-apocalyptic dystopia of a world destroyed by the nuclear warfare of World War III, has the archaic feel of Greek drama to it, with choral interjections and frequent commentary by the Narrator. Of course, as a screenplay, these are also interspersed with instructive descriptions of cinematography.

The primary storyline of the screenplay involves Dr. Alfred Poole, a botanist on an expedition to California from New Zealand with a team of scientists who are exploring the war-ravaged world that radiation levels have diminished. New Zealand itself, deemed “of no strategic importance,” was spared a nuclear attack. Most of the scientists are killed, and Poole manages to save himself and earn some level of favor by lending his knowledge and skills toward the effort of more effectively growing crops.

Poole finds himself enmeshed in a Satan-worshipping society the likes of which makes even most Philip K. Dick novels seem jocular in comparison. The clergy, all fat and sweaty eunuchs clad in goat skin, occupy the upper strata of the caste system, whereas commoners live in a state of near-slavery. Books are burned as fuel. In addition, all babies born mutated are killed. Of course, mutation is nearly universal due to the radiation, so only infants with more than seven fingers and toes or more than three pairs of nipples are killed. They are not simply euthanized, however. They are “liquidated,” impaled on a knife in a sacrificial mass murder in honor of Belial—Satan’s preferred name in this culture, although he is also referred to on occasion as Mammon, The Lord of the Flies, etc.

Breeding is strictly controlled. Women wear clothing with “NO” emblazoned strategically over all of what John Cleese famously called the “naughty bits.” Women are referred to as “vessels” and regarded the “enemy of the race, punished by Belial and calling down punishment on all those who succumb to Belial in her,” as explained to a young girl by the Satanic Science Practitioner. Sex is sanctioned and only occurs during a mass orgy; otherwise, it’s forbidden. After everyone has stood to watch every mutated infant be skewered and thrown into a pit, the Arch-Vicar—mystagogue of the Church of Belial and effectively head of state—ends a prayer with “His curse be on you,” and the crowd explodes into a chaotic, hedonistic frenzy of rape and carnal abandon.

Most of the philosophical dialogue occurs between Poole and the Arch-Vicar during the infanticide rituals in a lengthy conversation analogous to that of John the Savage and Mustapha Mond in “Brave New World.” Otherwise, Poole’s experiences are punctuated by the Narrator and the baboon vignettes, in which a line sung by a seductive baboon lounge singer is frequently repeated, and the line “Give me detumescence” is used as an appropriate motif. The baboons themselves posses leashed clones of Einstein who are forced to carry out sophisticated biological attacks on opposing groups of the baboons. It is never made clear exactly who the baboons are, but the parallel between the baboons and the society that has destroyed itself through World War III is clear, as is Huxley’s implicit social commentary regarding his—and our—own world.

Ultimately, Poole finds himself at the grave of William Tallis, who has written his own gravesite (albeit misplaced, geographically) into the book, foreseeing his own death and bringing the otherwise unresolved introductory chapter to some closure.

While it is an oddity among not only Huxley’s work but within modern literature, even in the niche of science fiction, “Ape and Essence” does contain some of his most effective imagery, as well as some of the most scathing ridicule of nuclear-age politics ever penned. Some would say that its structural quirks are its primary weakness; others might contend that they are a part of what make it particularly effective. It is certainly baroque and colorature in its presentation

Some of the content may raise an eyebrow for many parents, even though “Ape and Essence” is a far cry from smut. That is, if some parents were so intellectually stunted as to object to “The Catcher in the Rye” being taught in high schools, it’s imaginable that they would similarly fuss over “Ape and Essence.” However, it’s relatively brief, extremely accessible, and timelessly relevant and should be required reading in college English classes alongside all the other great coeval satirical novels.