Written By Marianne Mansfield

Written By Marianne Mansfield

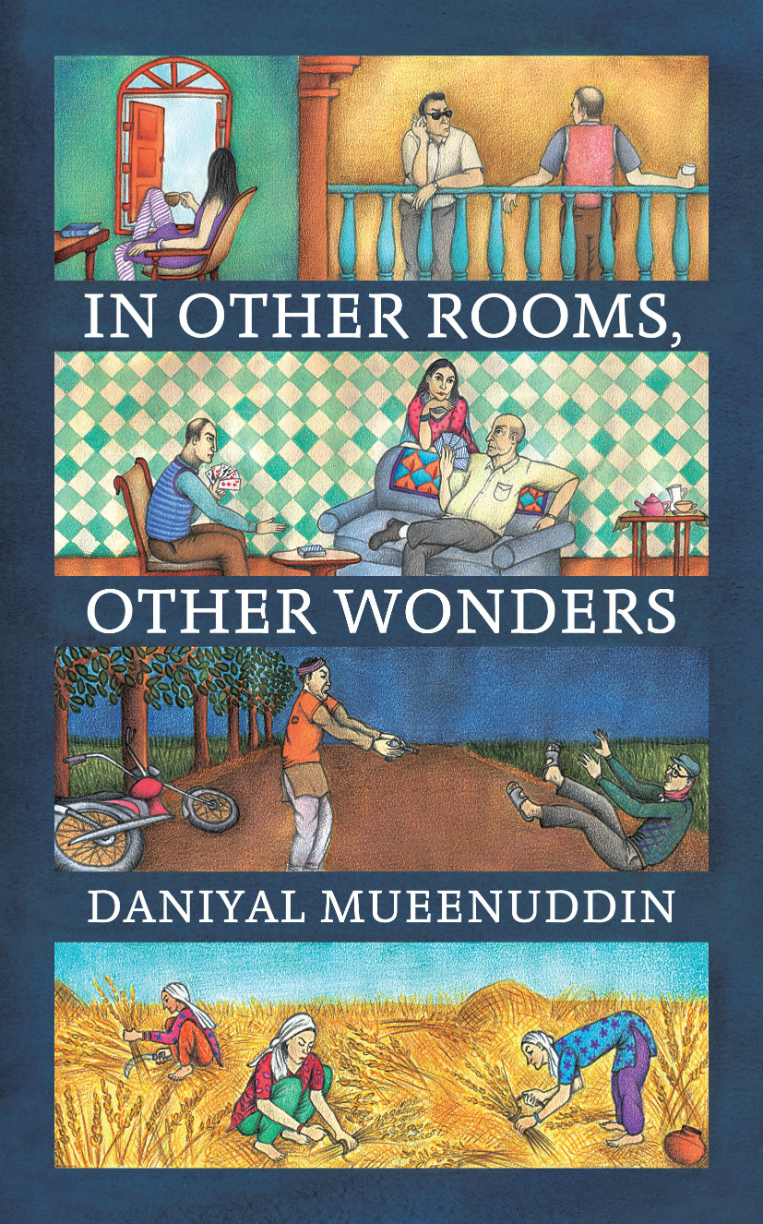

“In Other Rooms, Other Wonders” by Daniyal Mueenuddin

W. W. Norton, 2009. 256 pages.

Set in modern-day Pakistan, the eight interlinked stories in this volume tell a tale of the intertwined lives of an affluent landowner, his family, and his retainers in the town of Lahore. The beauty of the short story cycle genre is that the reader is invited into the drama of a place and time through the eyes of any number of actors on the stage.

Despite the Mueenuddin’s meticulousness as he describes the gardens and the houses the characters inhabit, the characters themselves are just as messy and cross-motivated as the people we run across in our own lives.

The class distinctions in modern-day Pakistani society form the network in which the characters’ individual stories are suspended.

Although he’s not the first character presented in the book, the reader soon realizes that K. K. Harouni, the aging landowner, is the central character to whom all other characters are connected. Benevolent but disturbingly self-absorbed and unbothered by the poverty around him, Harouni becomes obsessed with selling off his property to counteract a series of bad investments. While it appears that he is doing so to support all the servants and retainers, he really seems most concerned with protecting his reputation as he nears the end of his life.

We also meet an electrician whose skill is rigging the electric meters on the Harouni estate to cheat the power company. Nawabdin works hard to support his wife and 13 children and is particularly pleased when he is able to convince the landowner to supply him with a motor scooter to travel about the estate. The motor scooter, however, soon leads to a sudden reversal of affairs for Nawabdin and forces him into a life-altering decision about forgiveness and rightful possession.

The function of the female characters in this collection is complex and layered. The reader is invited into the lives of women who, because most do not possess marketable skills beyond working on the estate, use sexual favor as a means to provide for themselves and their children. The men they encounter are often married but begin to make questionable choices in their lives, because they love these women. Repeatedly, the author examines the dourness of marriages entered into because of family arrangement, contrasting it with the bounty of love offered by sensual women willing to trade companionship for security. Unfortunately, in the end, these deals seldom work to the women’s advantage. When the women realize their plight, the sadness is palpable.

For example, Rafik, the old valet and a gentle soul, becomes the target of Saleema, a young woman who seeks to escape her drug-addicted husband. She zeroes in first on the cook at the Harouni estate, but when he demands more than she is willing to give, he abandons her. Rafik is kind and has achieved some prestige in the hierarchy of the retainers. Saleema’s ruthlessness gives way to a genuine affection. Their tenderheartedness, however, does not end well for either of them, and by the time of Harouni’s death, both have learned expensive life lessons.

There are other workers on the estate into whose lives the reader peers, exposing the ups and downs of simply trying to live life. For instance, Rezak, the gardener, lives in a small box he carts from job site to job site. Content with the status quo when we meet him, he falls prey to simple greed and simpler lust, which tend to him like nursemaids at the end of his life.

The narrator of the stories is a sessions judge in the Lahore High Court. He explains, “despite my profession I don’t believe in justice, am no longer consumed by a desire to be what in law school we called “a sword of the Lord” nor do I pretend to have perfectly clean hands, so am not in a position to view the judicial system with anything except a degree of tolerance.” This could be the author speaking. The eye he focuses on his characters is unblinking and often harsh, but in the end, Mueenuddin seems to be possessed of an affectionate tolerance for the men and women of this book.

This is not a happy book, nor is it a sad one. There are moments enough of shining human compassion—the sweetness of the relationship between a mother and infant, and the steadfast loyalty that stems from tradition and the passage of time—to keep the reader moving from story to story, and sometimes back again. You root for the triumphs of these characters and lament their sorrows. And you miss them, even the old landowner, when they are gone.

Daniyal Mueenuddin, born in 1963, is a Pakistani-American author who writes in English. His short-story collection, “In Other Rooms, Other Wonders,” has been translated into 16 languages. It has been awarded The Story Prize, the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, and other honors.

Born in Los Angeles, California, Mueenuddin spent his childhood in Pakistan. At the age of 13, he moved to the U.S. where he received higher education and worked as a journalist, a director, a lawyer, and a businessman before finally devoting his efforts to writing.