Most drivers hate seeing those orange traffic barriers pop up on their favorite route. Sitting in a car and wondering why the Utah Department of Transportation—UDOT—decided to tear up the road is a common experience. The answer is can be found at a technically sophisticated UDOT website that the public can use to see exactly what is planned: UDOT UPlan.

There’s a price to be paid for the cool features that UDOT has integrated into their site, however. For example, some of the features on the site don’t work with all software. Microsoft’s Internet Explorer is currently incompatible with some features. UDOT is recommending Mozilla Firefox or Google Chrome for best results right now. Your PC or other Internet-connected device should also have “Java runtime” installed for some features. Finally, keep in mind that the site is under active development. The path to access the cool features might change anytime and is certain to change in the next few months. But the Independent found the UDOT technical help for their web site to be responsive and helpful.

Another thing to keep in mind is that this is a working tool for UDOT. The public is invited to take advantage of it, but many parts of the site are there for more specialized requirements such as coordinating with local government and contractors. In some cases, parts of the site can’t be accessed because they’re password protected. In other cases, special software or training is necessary to take advantage of them. But even with all these qualifications, there’s still a lot there that is worth looking at.

UDOT said that for most users, the UPlan section of their site is the most useful. According to UDOT, UPlan is a web mapping application that lets you access a collection of maps and data maintained by UDOT. To access UPlan, UDOT recommends that you start with the web address: uplan.maps.arcgis.com/home. Even though it’s an official website, this isn’t a “Utah.gov” web site. It’s an “ArcGIS Online” hosted website. As a result, UDOT doesn’t control everything on the site, and some of the links go to other commercial sites such as Picasa.

The UPlan home page lets users find information in several ways, but it’s easy to end up in a frustrating dead end. The recommended way to find UDOT information for southern Utah is to choose the Region 4 Gallery using your mouse to highlight the region in the Utah state map on the home page. The next page will show a list of maps and apps that can be selected.

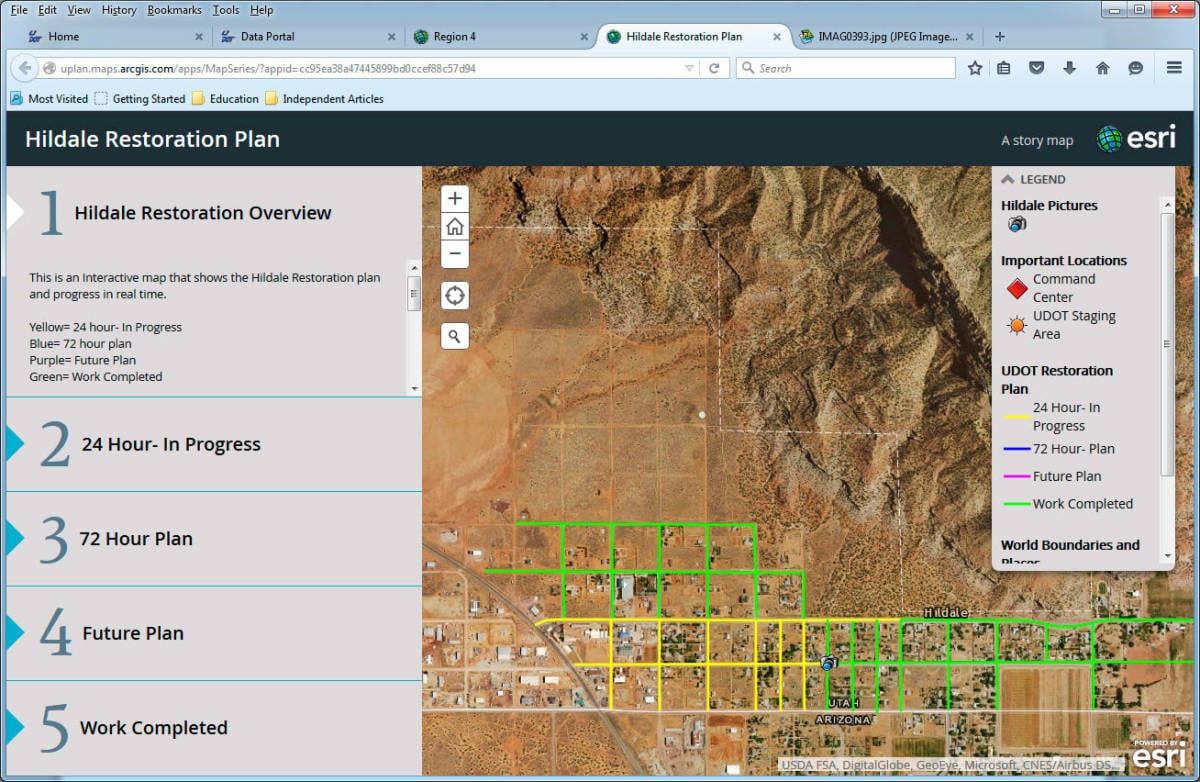

As an example, the progress that UDOT was making in cleaning up the flood damage in the town of Hildale is shown in a map that UDOT kept updated during the work. When this article was written, nearly all the work in Hildale was done with only a few streets still to be cleared.

courtesy of Utah Department of Transportation

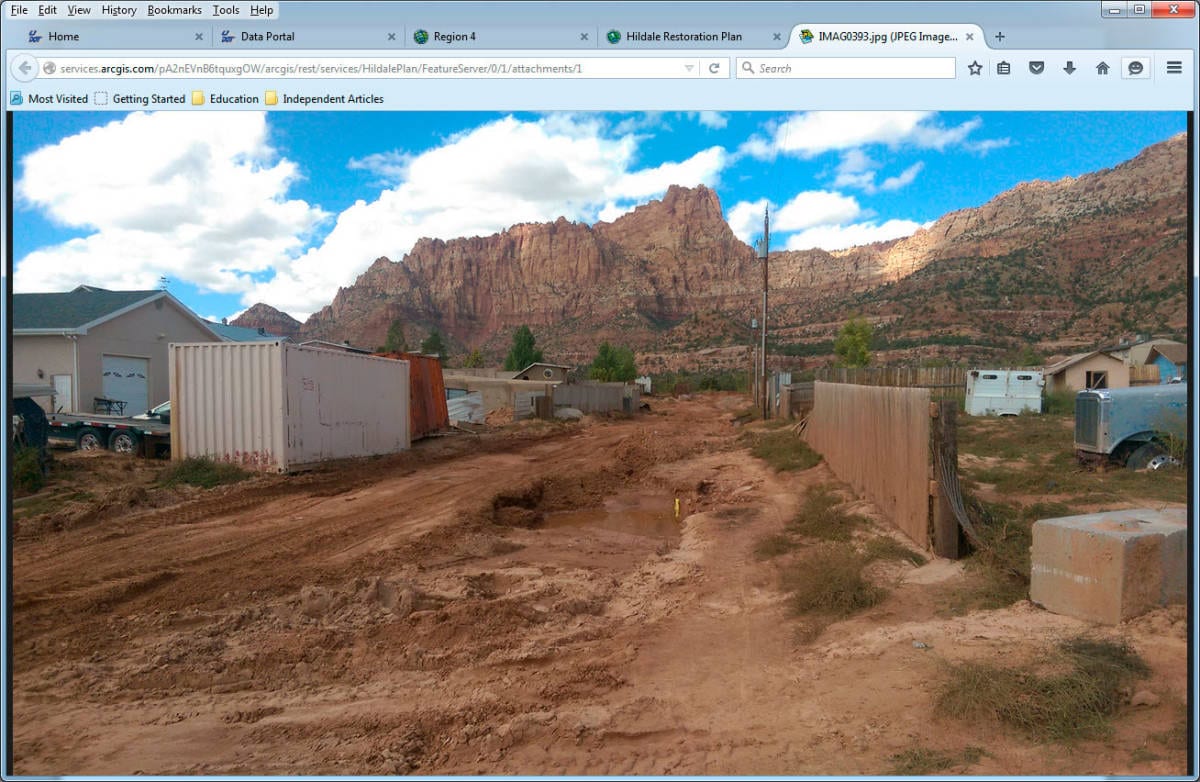

Clicking one of the camera icons on the screen displays a picture of the damage done by the flood at that location.

courtesy of Utah Department of Transportation

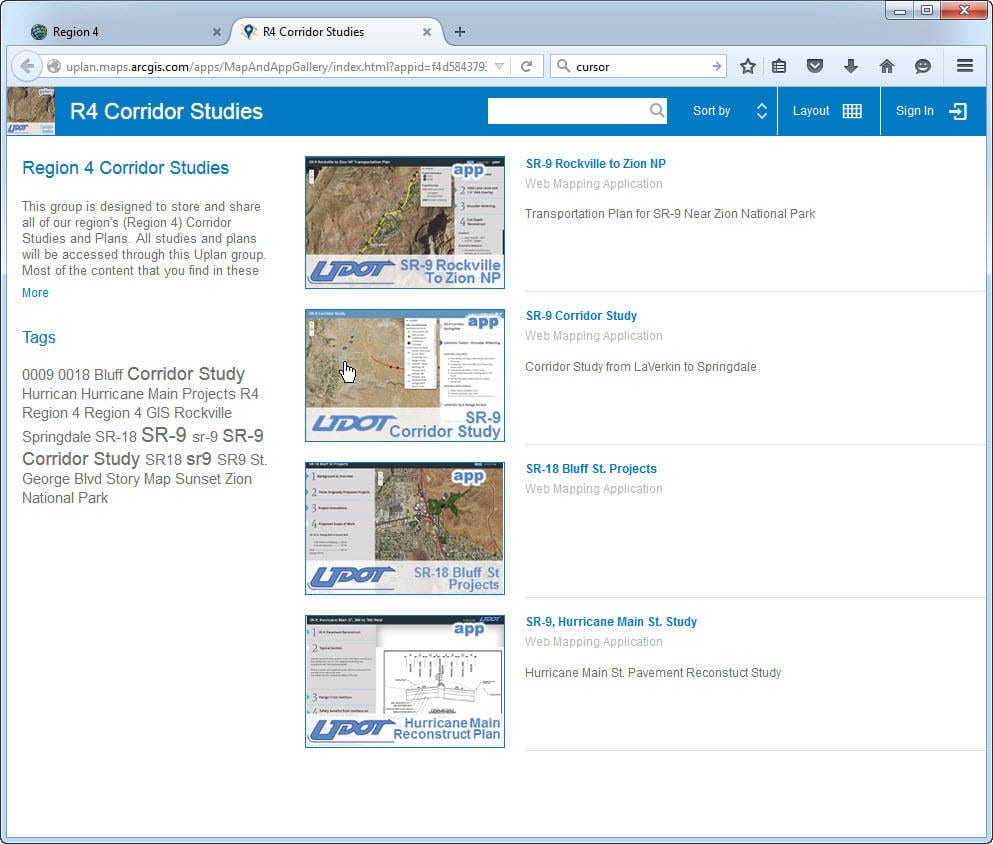

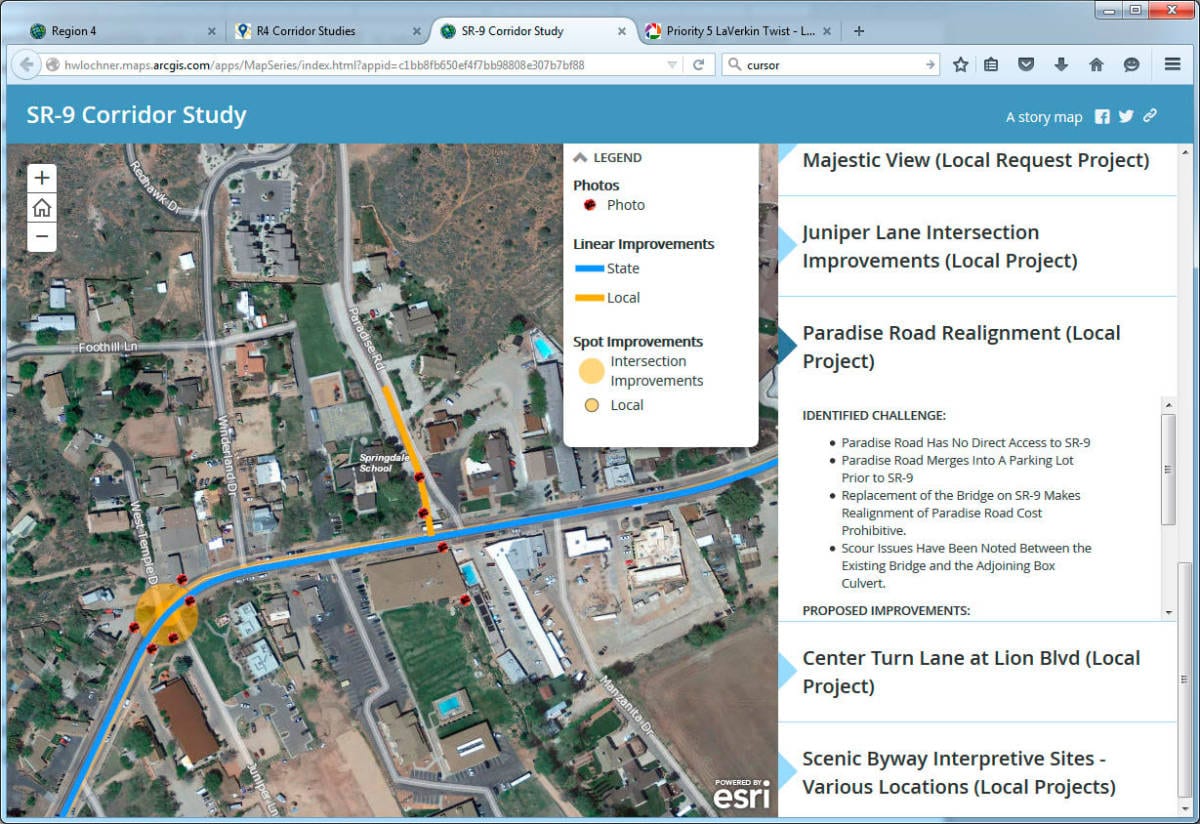

One of the most useful sections of UPlan is the corridor studies. These long-range plans combine planned and proposed improvements by both UDOT and local authorities in the same combined map.

courtesy of Utah Department of Transportation

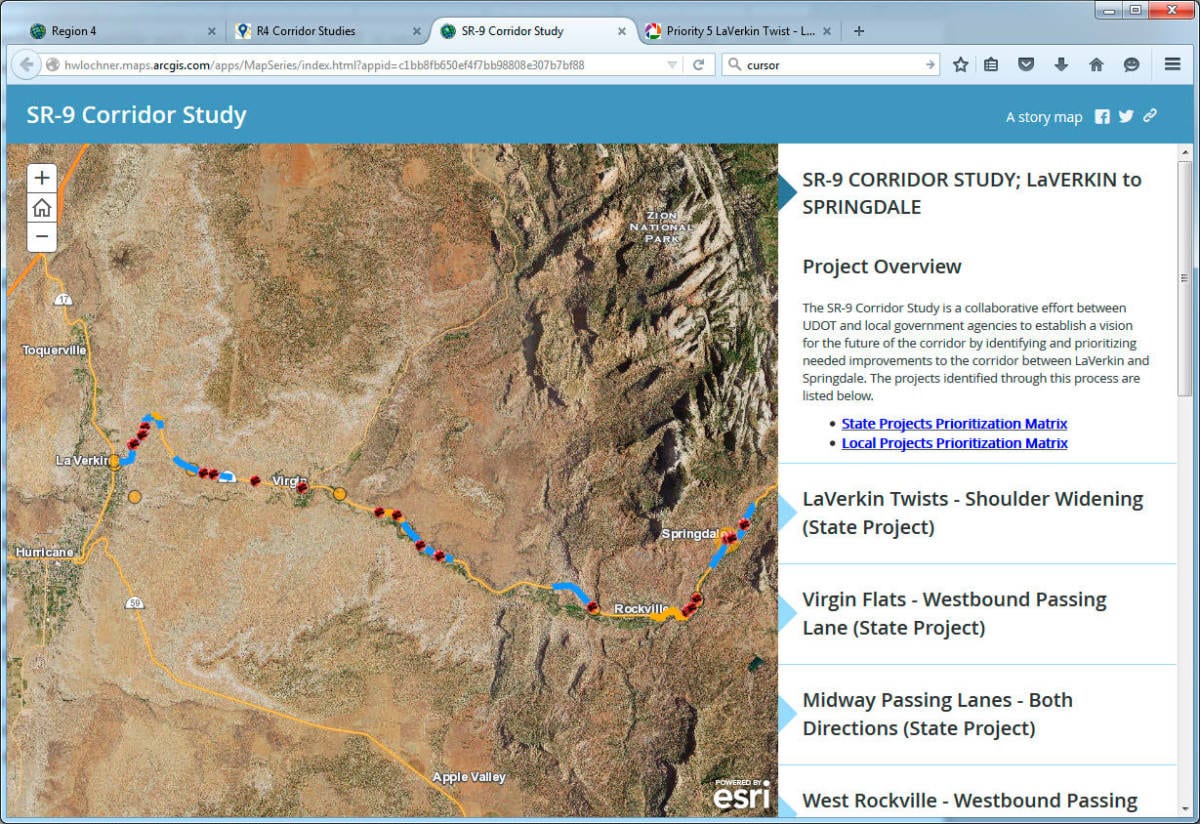

Dana Meier, UDOT Program Engineer, recently used UPlan to demonstrate UDOT plans to upgrade the busy State Route 9 corridor to the Springdale Town Council. This corridor from La Verkin to Springdale takes over 3 million visitors a year to Zion Park, so it’s of prime interest to Utah and UDOT.

One of several UDOT corridor studies available

courtesy of Utah Department of Transportation

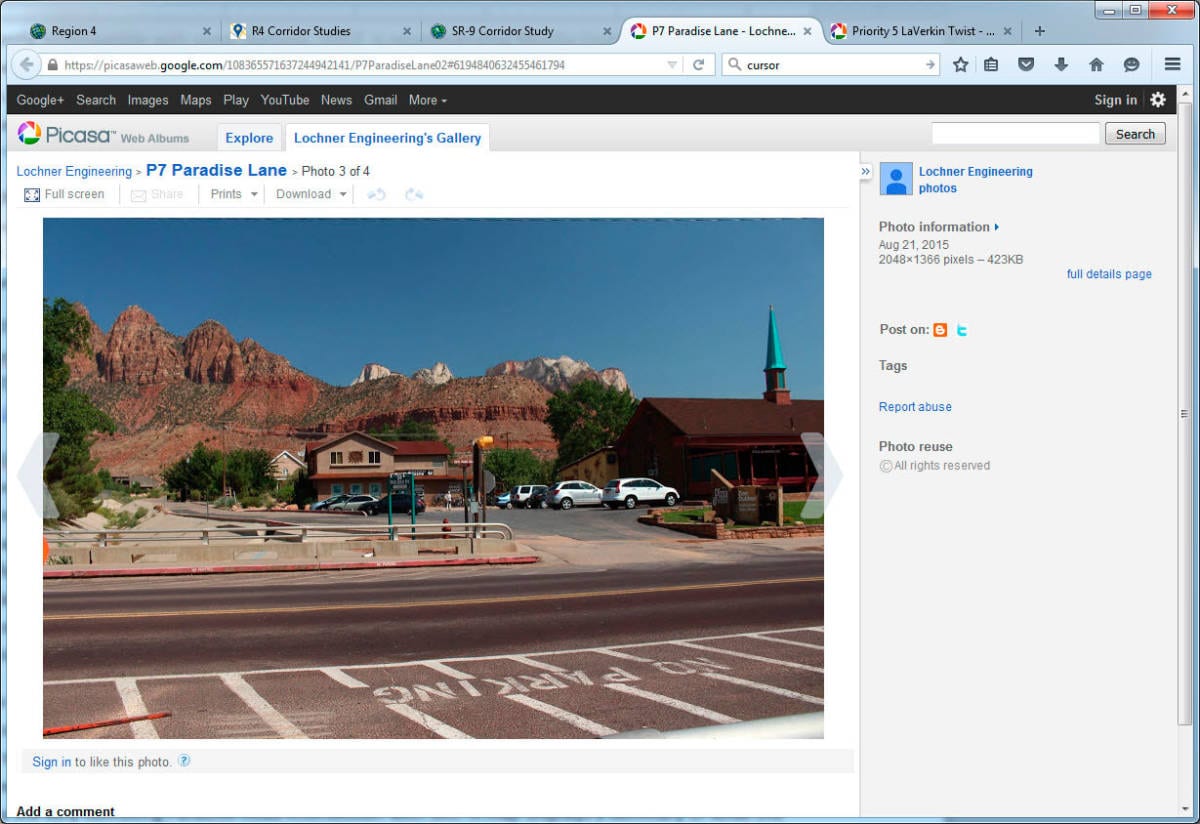

Meier was able to show the Springdale Town Council exactly what was planned for the anticipated improvements that will start next year. For example, the Paradise Road intersection with State Route 9 has long been a trouble spot in Springdale.

courtesy Utah Department of Transportation

A UPlan map displays a summary of what the problem is and how it will be fixed. It also documents that it will take over $3 million to do the job of fixing just this one intersection.

courtesy Utah Department of Transportation

Browsing the site can reveal interesting new things. For example, several of the photos of the State Route 9 corridor illustrate scenic views. A photo taken at the La Verkin Twists section of the road shows a geologic feature that Meier identified as a “slickenside.”

courtesy Utah Department of Transportation

Meier said that this is one side of the Hurricane fault where the rock has been polished by the movement of the fault over the millennia and that geology classes often stop to examine it.