Our Geological Wonderland: Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm

By Rick Miller and Andrew Milner

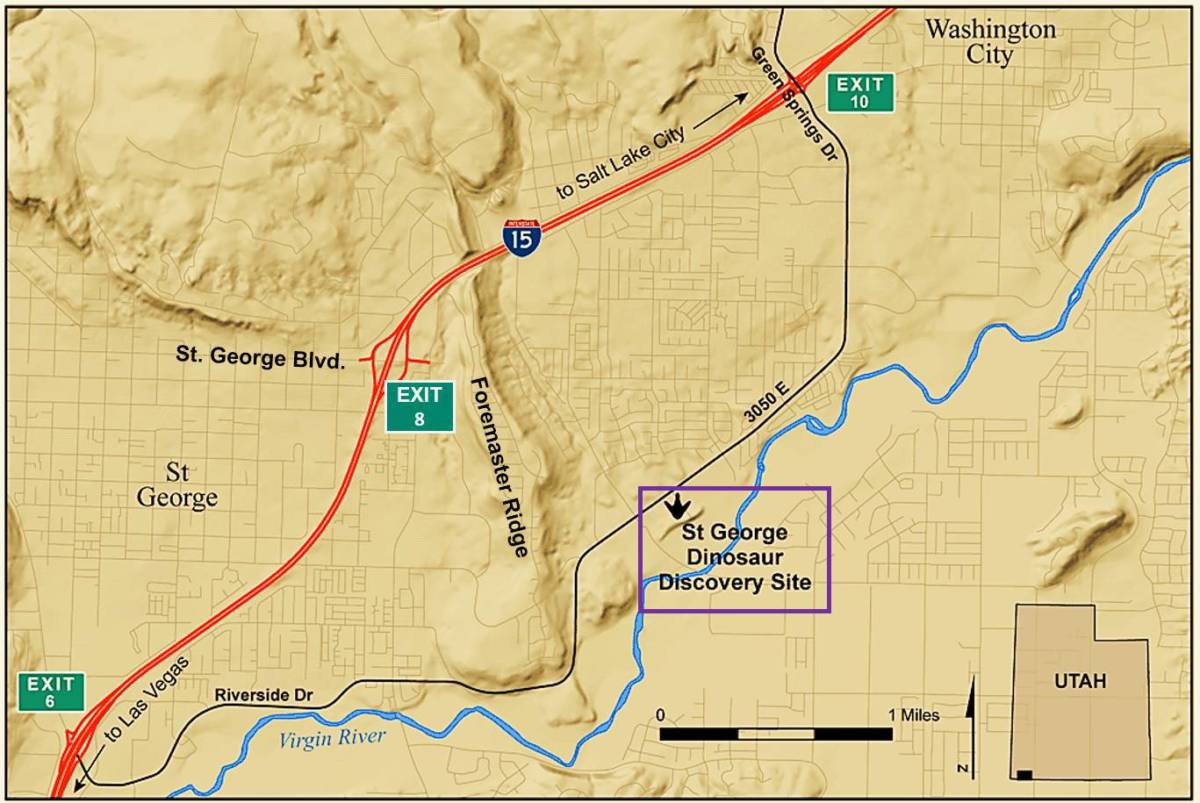

The phrase “footprints in the sands of time” represents but a fraction of the abundance and diversity of trackways and other fossils that have been recovered from the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm (figure 1). This site was discovered by accident but is now considered to be a world-class fossil site. A detailed account of this discovery, its development, and its significance is provided by a recently published book. “Tracks in Deep Time: The St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm” by J. D. Harris and Andrew R. C. Milner. It provides a lot of detail and pictures but is a relatively easy read for non-geologists.

On Feb. 26, 2000, Dr. Sheldon Johnson, a retired optometrist, was using a trackhoe and other equipment on his land in preparation for future development. During excavations, a slab of sandstone was accidentally flipped over, and Johnson noticed what appeared to be tracks preserved on the undersurface. Examination suggested that the tracks were those of dinosaurs. Checking other slabs further indicated that such tracks were common, so local geologists and paleontologists were contacted and visited the site. Within weeks of the discovery, the significance of the site was recognized, and Johnson and his wife, LaVerna, eventually donated the land and fossils to the City of St. George. With the aid of significant donations from federal, state, and city governments as well as private citizens, a museum was financed and built to preserve the tracks and other fossils. The museum opened in April 2005 (figure 2).

Additional discoveries on neighboring properties, especially those formerly belonging to Darcy Stewart, the Washington County School District, and Matt Musgrave, have added a great deal to our knowledge of the locality and the exhibits. The Dinosaur Discovery Site is now recognized as one of the most significant dinosaur track sites in the world for the interval of geologic time it represents. Features include exceptional preservation of tracks, abundant actual skin impressions, the largest and best-preserved collection of dinosaur swim tracks known, one of only 13 known sitting traces of a meat-eating dinosaur, and the only one of those with preserved hand impressions. There are 26 different layers of tracks preserving thousands of individual footprints and associated body fossils such as a variety of fish, plants, invertebrates, and rare dinosaur remains (figure 3).

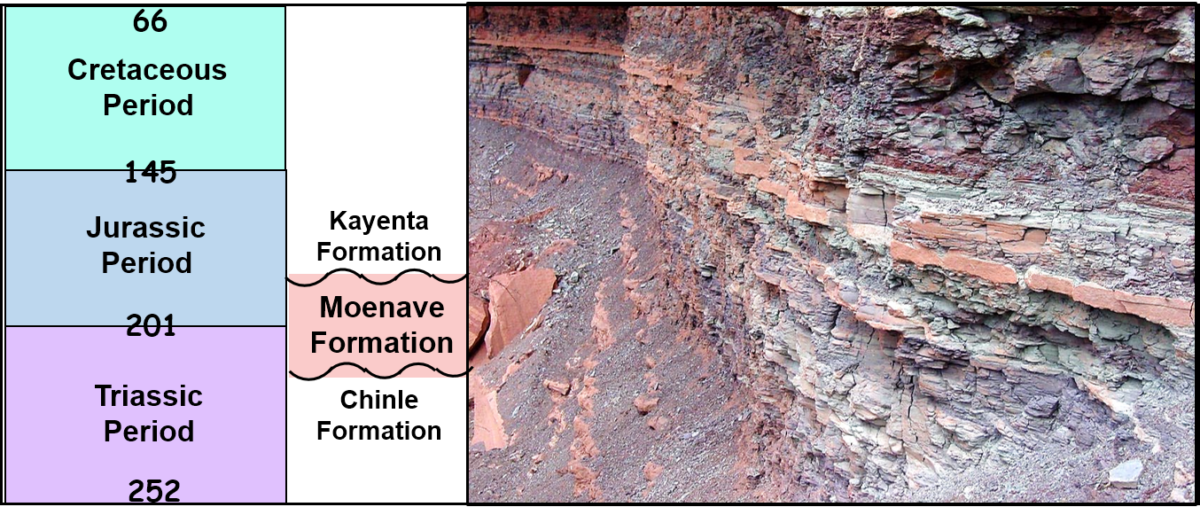

All of these fossils are contained within the Moenave Formation, which has a maximum thickness of about 235 feet in the St. George area, unconformably overlies the Chinle Formation, and is unconformably overlain by the Kayenta Formation (figure 4). The Moenave Formation consists of thinly interbedded layers of fine- to medium-grained sandstone, siltstone, mudstone, and shale and is considered to be very Late Triassic-Early Jurassic in age (about 200 million years old). Although not previously studied in detail for decades, Johnson’s discovery revived considerable interest in the formation, and numerous significant discoveries have since been made. Thus, this site has become an important addition to our knowledge of the Triassic-Jurassic boundary and the mass extinction for which it was originally established.

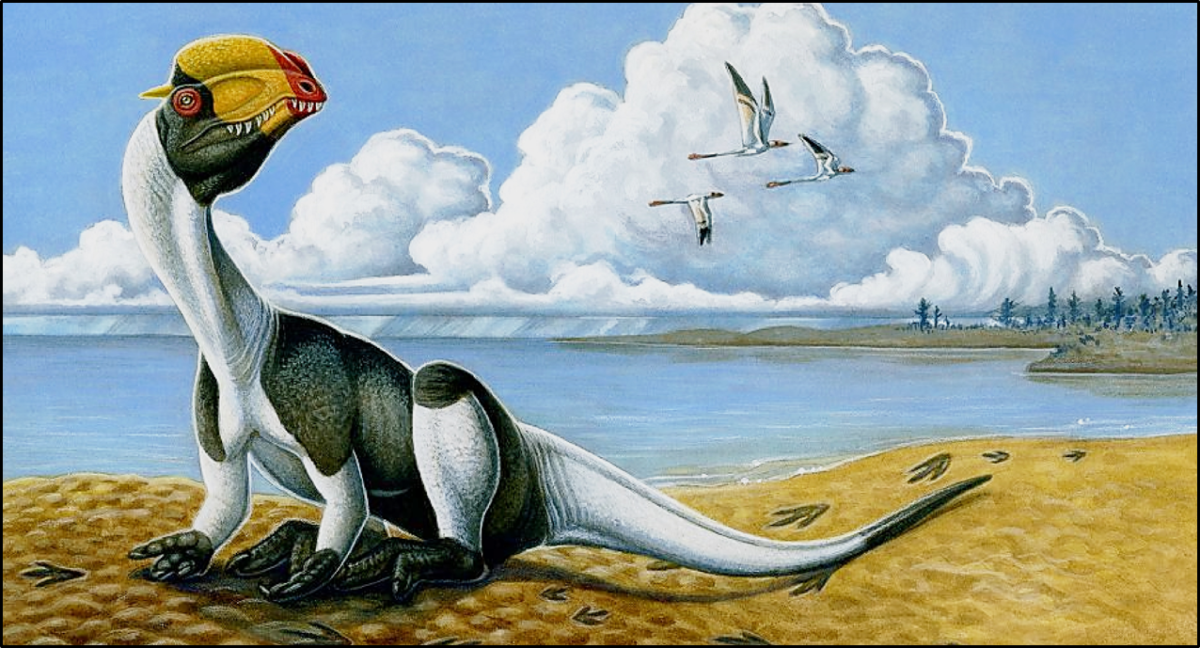

The Moenave Formation is divided into two members: a lower Dinosaur Canyon Member, which represents large, meandering river systems that flowed from the southeast toward the northwest; and an overlying Whitmore Point Member, which represents a large lake appropriately named Lake Dixie (not related to Ice Age Lake Bonneville to the north) that covered southwestern Utah, northwestern Arizona, and parts of southeastern Nevada (figure 5). The terrain was flat-lying and close to sea level as the Rocky Mountains had not yet formed. At that time, southern Utah was situated about 20 degrees north of the equator and had a subtropical climate with severe dry seasons and heavy monsoon seasons similar to the Okavango Delta today in Botswana.

To the west, volcanic island arcs formed along the Pacific coast approximately where the California-Nevada border is positioned today. Located to the east of the upper part of the Dinosaur Canyon Member and the Whitmore Point Member was a large sand sea (known as an erg) represented by the Wingate Sandstone.

Fossils, trace fossils, and distinctive, well-preserved sedimentary structures such as ripple marks, mud cracks, etc. are preserved within the Moenave Formation (figures 6 and 7). These fossil remains and sedimentary structures provide evidence used to reconstruct the environments that existed at that time. It is like a geological and paleontological version of a television detective program where evidence is collected to determine the nature of a crime. Body fossils such as bones, teeth, shells, wood, and sometimes soft parts found in rock formations provide evidence of what certain animals and plants looked like when living (see figure 5 above).

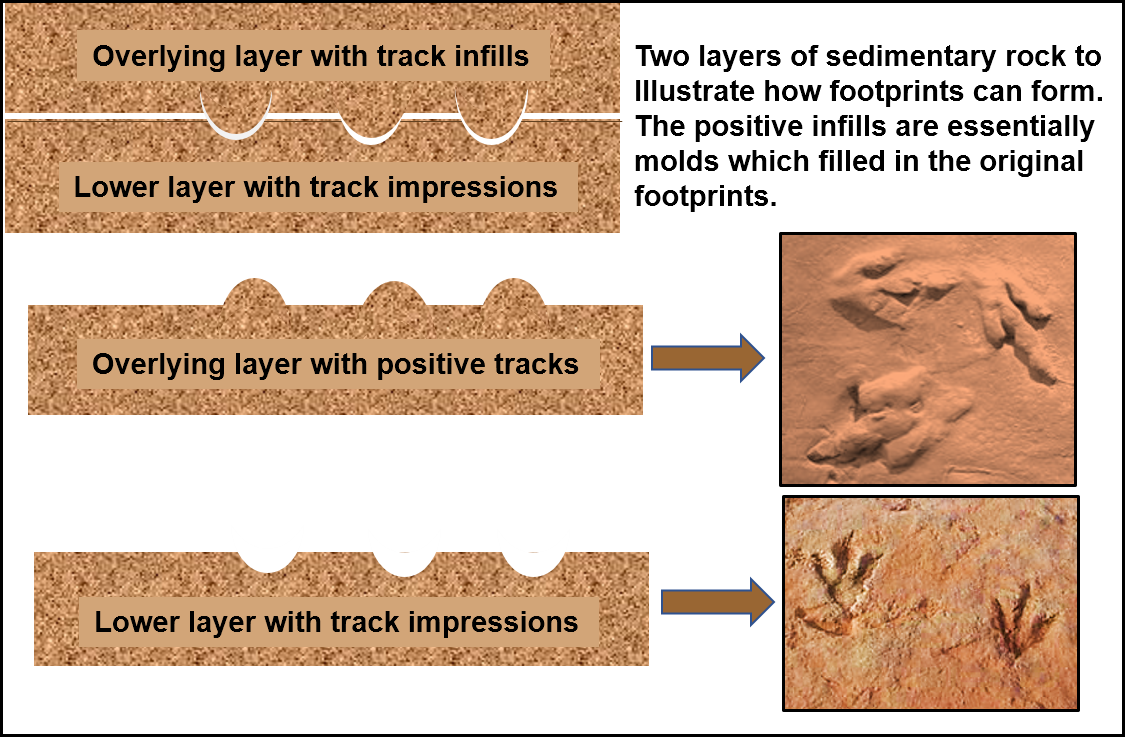

Preserved on the surface of many layers within the formation as both natural molds and casts are a variety of footprints, trackways (figure 8), and other trace fossils such as burrows and coprolites. These trace fossils tell us a great deal about animal behaviors such as walking, running, gregariousness, swimming, sitting, limping, burrowing, etc. Many important behavioral traces are represented at Dinosaur Discovery Site and greatly increase the geological significance of the locality.

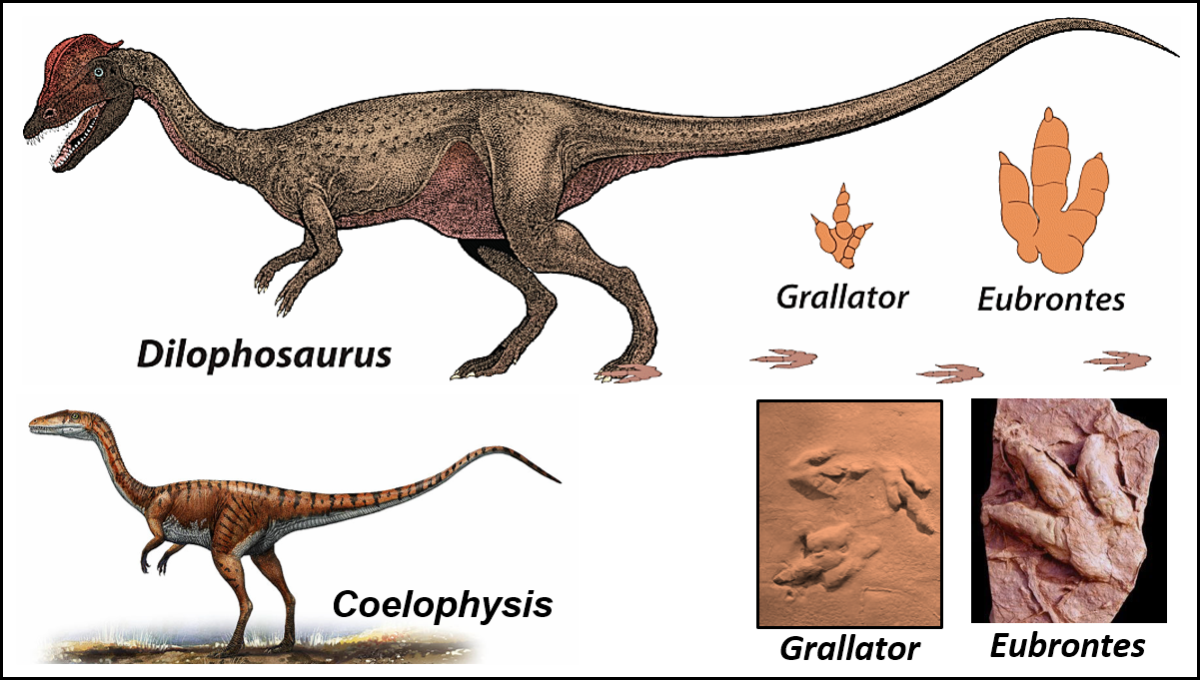

A taxonomic complication occurs with these fossils. As with body fossils, trace fossils require scientific names that are different from the names of the actual animals that may have produced them. For example, the trace fossil eubrontes represents the footprint of a medium-sized theropod dinosaur. The dinosaur Dilophosaurus is considered a possible source because the arrangement of bones in its foot match well with the toe pads seen in the tracks. However, not all eubrontes tracks may have been made by Dilophosaurus. These tracks may have also been made by other kinds of meat-eaters that were closely related to Dilophosaurus or others currently unknown to science.

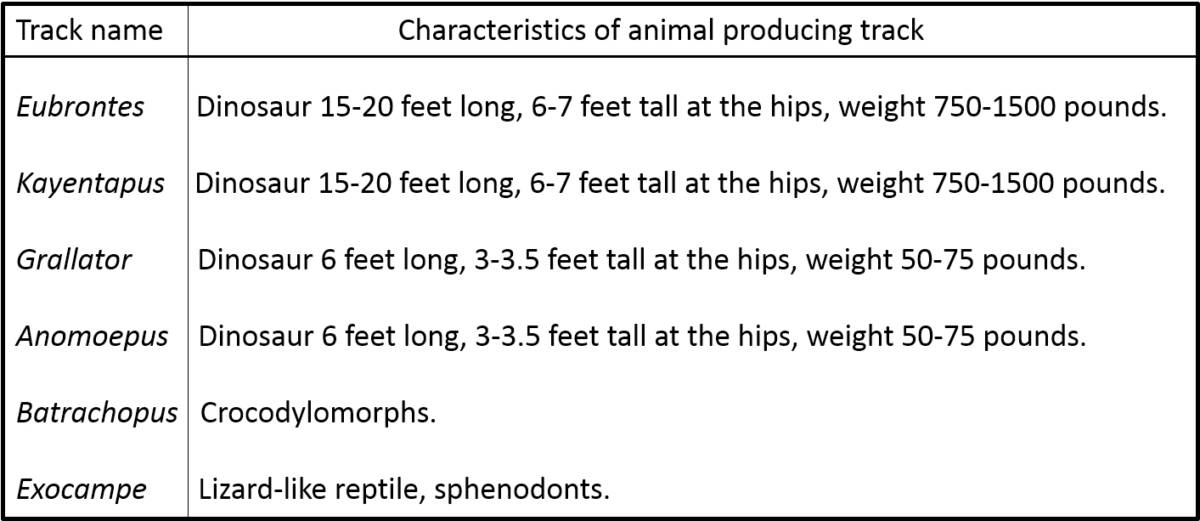

To date, vertebrate tracks identified at the Dinosaur Discovery Site include the Ichnogenera Eubrontes, Kayentapus, grallator, Anomoepus, batrachopus, and Exocampe (Table 1). As explained above, Eubrontes and Kayentapus tracks were produced by medium-sized theropod dinosaurs similar to Dilophosaurus. As adults, these theropods were 15–20 feet long and about 6–7 feet high at the hips and would have weighed between 750 and 1,500 pounds. The most abundant theropod dinosaur tracks at the site are called grallator and they were likely produced by smaller theropod dinosaurs similar to Coelophysis. Adults reached a maximum length of 6 feet, stood 3–3.5 feet tall at the hips, and probably weighed between 50 and 75 pounds (figure 9).

The geologically oldest known examples of the track type Anomoepus have also been found at Dinosaur Discovery Site. These rare tracks were produced by plant-eating dinosaurs that were comparable in size to Coelophysids.

Non-dinosaurian tracks are also represented at Dinosaur Discovery Site. Batrachopus tracks are very common with hundreds of specimens recovered and/or still in position on existing tracksites both within and outside of the museum building. Batrachopus tracks were produced by crocodylomorphs, which were mostly small and walked on all fours. They had double rows of armor along their backs like their present relatives, crocodiles and alligators.

The rarest track type at the Dinosaur Discovery Site is called Exocampe. These very small footprints are suggested to have been produced by a group of lizard-like reptiles called sphenodonts, which were very common during the Triassic and Jurassic. Today, there is only one living species of sphenodonts — tuatara — which lives on the north island of New Zealand.

Two kinds of fish-swim trace fossils are known from Dinosaur Discovery Site: undichna and parundichna. These traces were formed by the anal and caudal fins dragging through fine sediment as a fish swam along the bottom. Occasionally, the paired fins (pectoral and/or pelvic fins) can also leave traces. Certain species of prehistoric and modern fish also create structures called fish nests, which are often circular depressions excavated by fish to brood their young. Structures similar to these have also been found at the Dinosaur Discovery Site in association with fish-swim traces.

A wide variety of invertebrate traces include rare trackways of beetles, other insects, and even freshwater horseshoe crabs. Evidence of burrows formed both in submerged conditions and onshore show evidence of feeding behaviors while other burrows were living and/or brood chambers.

Body fossils also occur within the Moenave Formation and include several kinds of plants, invertebrates, fish, and dinosaur remains. Invertebrates include small bivalved ostracods, which provide evidence for environmental conditions and indicate an age of Early Jurassic. One freshwater dwelling shark has been named in honor of Sheldon and LaVerna Johnson for their contribution to science. It is known as Lissodus johnsonorum. Rare preserved teeth and a single, well-preserved anterior dorsal vertebra indicate the presence of a Dilophosaurus-like dinosaur.

The Dinosaur Discovery Site is located within the city of St. George (figure 10). It houses significant geological and paleontological remains from early in the age of dinosaurs. The entrance fee is minimal, and there are helpful staff and guides if needed. Displays are accessible, and much information about them is provided by many charts, graphs, and even a short video presentation. Overall, it’s a great location to learn something about the Earth’s history.

It is a bit awe-inspiring to realize that you are standing where dinosaurs roamed 200 million years ago (figure 11)!

Andrew R. C. Milner is the site paleontologist and curator at the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm. He has been at the site since its inception and now runs the museum’s preparation laboratory and conducts fieldwork in southern Utah. Milner has worked for the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, Canada on Ice Age fossils from that region, and the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto for five season at the Burgess Shale in British Columbia.

Articles related to “Our Geological Wonderland: Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm”

Our Geological Wonderland: A trip through the Virgin River Gorge

The famous inverted topography of basalt lava ridges of St. George