Written by Alex Ellis

Since the beginning of the “Black Lives Matter” movement in 2013 following the death of Trayvon Martin, racial tensions in the U.S. have been rising. With every killing of African American citizens by police—including Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Freddie Gray—citizens have become more and more discontent with a system that seems to discriminate along racial lines. However, the recent killing of Freddie Gray on April 19 provides the glimpse of change not often seen before: whereas the officers who killed Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and so many others were let go with little-to-no punishment, the six officers involved in Gray’s death have been charged with crimes ranging from illegal arrest to second-degree murder. In light of this news, Baltimore residents flocked to the streets in celebration, defying the curfew that had been set in place by Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake.

While many see the convictions as a victory, the waves of criticism from those both in support and against the Baltimore protests and riots have not been held back. Some claim the riots are an example of pointless violence, pointing to the number of African-Americans in government offices as “proof” that racism is dead. Others acknowledging there is still a problem but still disapprove of the riots and call for nonviolent methods of protest.

While nonviolence may be able to stand on its own in a more perfect world, this imaginary world of peacefulness sadly does not exist in reality. African Americans are upset and violent. And rightfully so.

Despite the continuous claims that racism died with the victory of the civil rights movement, the United States continues to see discrimination along racial lines. While making up only 12 percent of the population, African Americans accounted for nearly 40 percent of the prison population in 2009. When one follows the disparities between how African Americans are treated compared to white Americans, similar trends begin to appear, such as the following:

– African Americans are six times as likely to be incarcerated compared to white Americans.

– They are more likely to be arrested for drug related crimes.

– One in three African American men will go to prison.

– They make up 28 percent of juvenile arrests.

The list continues on.

While these statistics may be disheartening, it is important to recognize their origins in class and poverty.

Even though racist attitudes towards blacks began during colonial times, it was not until after the Civil War that the modern manifestations of racism in the U.S. began. Following the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865, millions of black Americans found themselves suddenly free from the shackles of slavery. While in a better position than they had been while in bondage, many questioned what to do with their new-found freedom. Left with little more than the clothes on their backs, many ex-slaves found themselves directly at the bottom of the American socio-economic scale. While the Freedmen’s Bureau was created to help these ex-slaves get back on their feet, the dissolution of the bureau in 1872 combined with the rising popularity and militancy of the KKK created a period for African Americans arguably more difficult than the years during the Civil War.

As racist attitudes put African Americans in poverty, their low position on the economic scale only helped perpetuate those attitudes. Not only were they hated by the disenfranchised planter class, but black Americans also received negative treatment from poor working whites who saw them as competition for jobs and believed they lowered the value of their labor, similar to how many modern working class Americans feel animosity towards today’s poor or migrant workers. On top of this, African Americans also had to deal with living in a country with extremely low economic mobility, another problem that continues on today.

With this in mind, it should come as no surprise that 27 percent of all African Americans currently live below the poverty line, with the number rising to 38 percent for African Americans under the age of 18. Compare this to the poverty rate of less than 10 percent among white Americans, and it become undeniable that the issues of race and class are closely intertwined. Even the poverty rates of Baltimore and Ferguson—both recently having been the epicenters of racial tensions—closely reflect these problems with poverty rates of 24 percent and 25 percent respectively.

The claim that racism in the U.S. was defeated in 1968 is demonstrably untrue; however, those who make this claim have a point that is often overlooked by their opponents. With the passing of the Civil Rights Act and similar legislation, the leviathan of naked, unashamed, legal racism by businesses and government entities was slain. Although this was a monumental victory, it created new problems for minorities; unlike the beast which Dr. King and his supporters faced in the 1960s, the problem of racism African Americans face today does not stem from any clear-cut entity. There is no specific organization to fight, no politicians to be removed from power, and no laws that can be passed to remedy the problem. Rather, the problem of racism today manifests itself in cultural norms, economic disparities, and a widespread belief that racism is dead. While this makes the power of racism carries less consolidated, it also makes it much more difficult to fight.

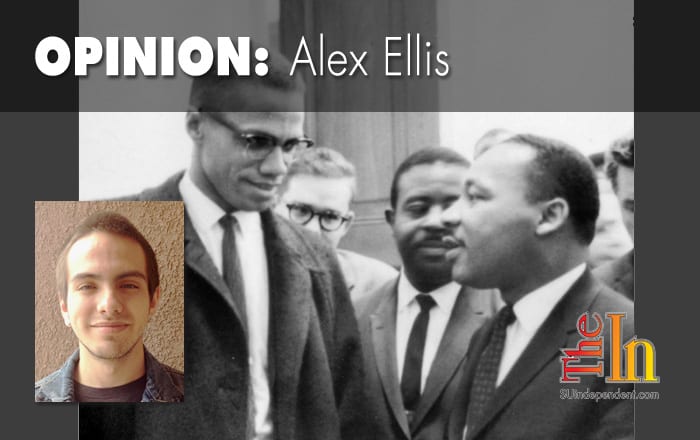

This is why violence against racist institutions is necessary. Nonviolence is a good tactic for building support and humanizing the oppressed, but it is powerless in the face of dispersed racial violence. Though pacifists are happy to parade the accomplishments of nonviolent movements, a closer look shows the violent tendencies that helped such movements as civil rights and the Indian independence movement succeed. Behind Dr. King there was Malcolm X and the Black Panther Party, who helped push back the tides of police brutality and created pressure for government reform. Behind Ghandi there was Bhagat Singh, who radicalized the Indian youth and British imperialism and is remembered as a martyr by the Indian people.

While it is important for nonviolent leaders to act as figureheads and negotiators to both the public and the enemy which they are fighting, the violence found in every social liberation movement will always be the flip-side of the coin.

Even Martin Luther King, famous for his nonviolent tactics, once stood up and said, “It is not enough for me to stand before you tonight and condemn riots. It would be morally irresponsible for me to do that without, at the same time, condemning the contingent, intolerable conditions that exist in our society. These conditions are the things that cause individuals to feel that they have no other alternative than to engage in violent rebellions to get attention. And I must say tonight that a riot is the language of the unheard.”

The protests in Baltimore reached such violent levels because the protests were a retaliation to the violence enacted against those who dared speak out. Even more, they were a retaliation to the institutional violence enacted against African Americas today, the same violence which caused people like Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, and Michael Brown to pay the ultimate price. Until America is ready to sit down and face the issues of modern racism head on, we can expect to see scenes similar to what has happened in Baltimore, Ferguson, and New York again and again. Until such a time comes, violence against a system that not only perpetuates but also ignores violence along racial and class lines will always be justified.