Written by Marcos Camargo

A couple years ago, I put in an application with the Washington County Sheriff’s Department to take a ride-along with one of its patrol officers. Nearly two months later, I received a call telling me that my request had been approved. Unlike most other ride-along participants, I was not interested in shadowing the police because I wanted to join law enforcement. Rather, I had a long time interest in gaining a greater understanding of what our public servants do and how they do it. The officers with whom I met showed nothing but respect and professionalism in the course of their duties. They were straightforward in answering my questions and resolving my preconceived misconceptions. I was impressed with the way they treated me and other citizens they encountered that day. The evening turned out to be quite uneventful. Only one incident caused me to pause and question the officer’s tactics.

While on lunch break, a call came in that reported a drunken man who yelled at his family and then barged out the door into the darkness. During the canvas of the man’s neighborhood, the officers found an unlocked door at a local business. While I waited in the car, my escort informed me they would be conducting a sweep of the premises to make sure nothing nefarious had gone on inside. To my surprise, the officer reached into the back of his patrol vehicle and pulled out an AR-15. Suddenly I had the feeling that the police had switched from public service mode to combat mode.

This was probably an over-reaction on my part, but I still went away from the experience with a strange feeling. Why have police forces made it a widely accepted protocol for regular patrol officers to carry high-powered assault rifles? And why do police feel that every time they enter a dark building, they must be armed to the max with military style weaponry? To answer this question, I think we must turn our attention to a long history of gun culture and what it means to be both a cop and a criminal in America.

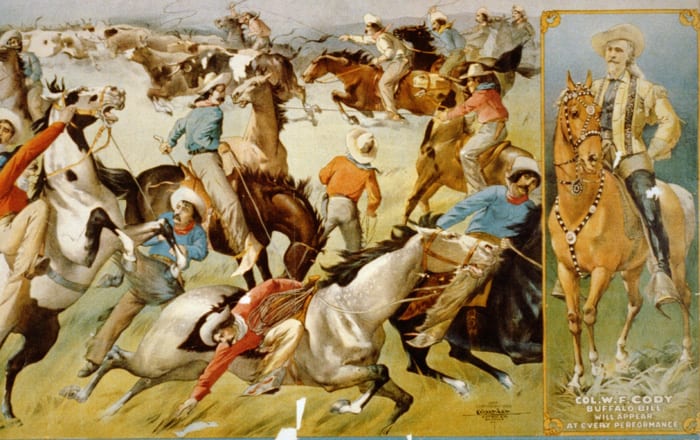

Part of the accepted mythos of the American experience is the notion of a perpetual frontier, a rugged individualism, and a distrust of both government and our own neighbors. This frontier mentality can be seen in the popular stories of the so-called “Wild West,” a place where a man could rely on no one but himself. It was an environment of hostility, an anarchy of sorts. When Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday took on the notorious cattle rustlers known as the Cowboys, they were forced to match the outlaws gun-to-gun until a final showdown that ended in a bloodbath of violent retribution.

This narrative is what we Americans have come to accept as the norm. And as time goes on, nothing seems to change. Every patrol officer in the United States carries a gun. It’s what we expect, and there’s something in the idea that seems to give us comfort. I should note that some other countries, Britain among them, have very few armed officers. Guns are reserved for SWAT and other specialized police units, yet London has some of the lowest gun homicide numbers of any major world metropolis. But even in the U.S., the now typical protocol of issuing weapons of war such as AR-15s to every man and woman in blue has only emerged in the past few decades.

So why is it that police have adopted this practice of intense militarization? Among many factors, one incident in particular that had an enormous impact on transforming police from neighborhood defenders outfitted with sidearms into fully equipped paramilitary operators with assault weapons was the 1997 North Hollywood shootout.

Details in the shootout need only be recounted briefly. The incident followed an attempted bank heist and involved two heavily armed bank robbers, Larry Phillips and Emil Mătăsăreanu, and Los Angeles County police forces. The robbers took no hostages and fled the bank when police confronted them. The ensuing shootout lasted less than one hour. In that time, both Phillips and Mătăsăreanu were killed, eleven officers and seven civilians were injured, and over 2000 rounds of ammunition were fired. Because the robbers employed military style assault weapons, the high profile case drove police forces around the country to build high-powered arsenals.

|

| Phillips and Mătăsăreanu |

In a way, I can hardly blame them. What happened in Hollywood stands as a testament to the violence and hatred of so many criminals. But my question is this, instead of always upping the ante, instead of always outgunning potential madmen, instead of adopting an ever-escalating mindset of combating violence with violence, why don’t we turn our attention to mitigating violence?

It’s been suggested that Phillips and Mătăsăreanu may actually have legally obtained the firearms used in their crime. However, whether they employed lawful channels of purchase does not matter. What matters (and I ask you not to shoot the messenger) is that in America it is too easy to get a gun, and it is especially too easy to get a gun that is designed for nothing more than killing the largest numbers of people in the quickest possible way. America is so prolific at producing and selling firearms that nearly every weapon owned by the Mexican drug cartels originated in the U.S. The biggest tragedy of Operation Fast and Furious is not that Eric Holder, et al. lost track of the guns used in the sting. The true tragedy is that anyone at anytime can purchase a gun in America with ease.

I am not saying I think guns should be outlawed. I come from a long line of frontier families. I understand that hunting is a legitimate and healthy American pastime. I even believe that firearms can and should be legal for protection in a person’s home. All I am trying to get across is that gun laws in their present form constitute a complete model of insanity. An excessively armed criminal element has led directly to an excessively armed police state. The adoption of universal background checks, the registration of firearms, and limitations on certain types of weapons would do nothing but protect the public and make it easier for law enforcement to take a more even-handed approach.

In the wake of so many tragic police shootings, I believe much can be done to reform police departments and their protocols. Body cameras are a step in the right direction, as is better oversight and reporting to ensure that police do not discriminatorily target certain groups. But as a society we will never be able to temper police violence until we can temper the violence of our own citizenry.

Marcos Camargo grew up in the rural heartland of Oregon. In 2003 he moved to Utah to find his place in the world and fell in love with the deserts of America’s arid country. An avid student of history and politics, he has a great interest in Western and Native American history and culture. He spends his free time exploring the wilderness of the Southwest.

Marcos Camargo grew up in the rural heartland of Oregon. In 2003 he moved to Utah to find his place in the world and fell in love with the deserts of America’s arid country. An avid student of history and politics, he has a great interest in Western and Native American history and culture. He spends his free time exploring the wilderness of the Southwest.