By Ryan Rutkoskie

By Ryan Rutkoskie

The Trump administration was greeted by approximately two weeks of full-on indignation, where the masses took to the streets and many “productive” members of society protested for the first time. The angry crowds marched and chanted through blocked-off roads. For most people, however, it amounted to trading one’s perceived ability to determine the fate of their country to the ability to disrupt traffic and create detours for other faceless crowds who probably agree with them. It was a losing battle to inconvenience the inevitable. Eventually, the sequence of events on Capitol Hill became too absurd to fuel the average person’s political activism and keep the streets full of people speaking on behalf of the disenfranchised, reality-driven majority.

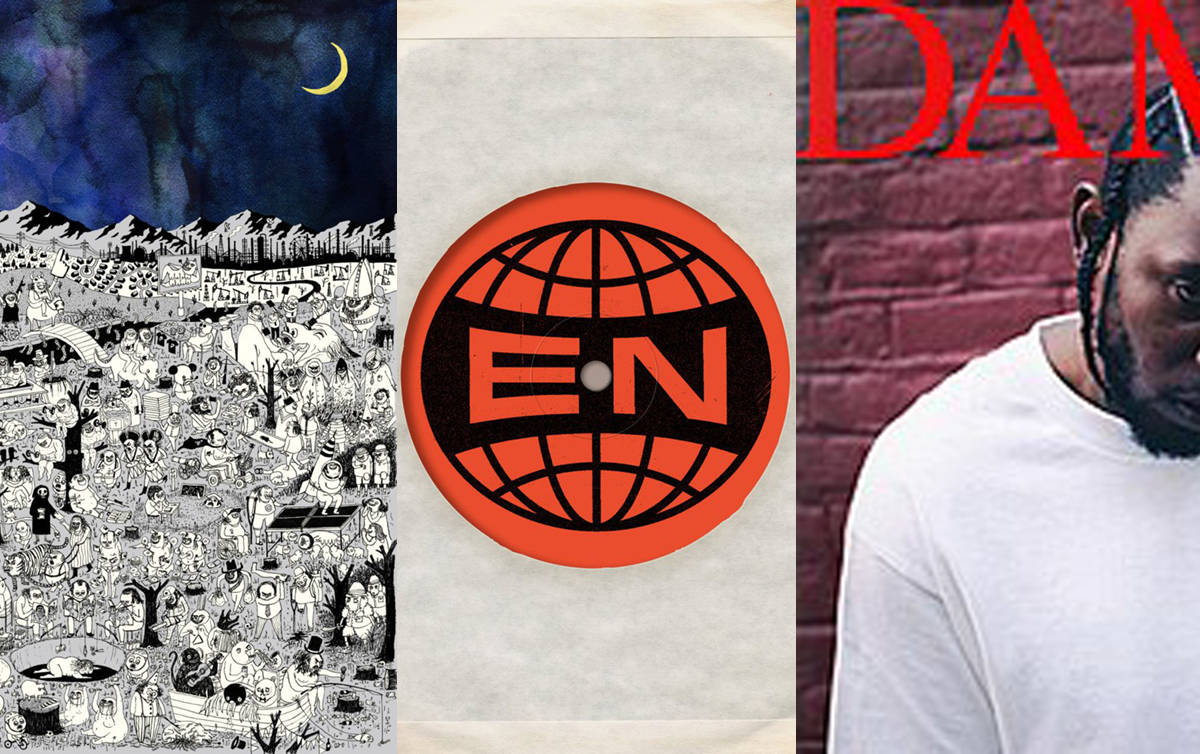

As post-Trump chaos enveloped our world, there seemed to be a cultural demand put upon songwriters to react with passion or optimism. However, a very different statement is emerging, one that is utterly hopeless. Artists are widely rejecting the burden placed upon them to be our champions and show us the way forward. The fact that such an overwhelming majority lost this election — when we’ve been falsely described as a democracy for so many years — along with the extreme cultural regression and lowering of standards and the relativity ascribed to facts and the nature of reality itself creates an environment that gives the artist little incentive to be persuasive or defiant. We’ve reached a perceived cultural zenith of absurdity that breeds either delusion or defeatism. These new attitudes are on display throughout the current releases of Father John Misty, Arcade Fire, and Kendrick Lamar, to name a few.

Throughout “Pure Comedy,” Father John Misty treats humanity with equal parts pity and contempt. Father John Misty writes of the philosophy of his own album, “What if instead of imbuing our expectations for the quality of our lives to include perpetual happiness, dream fulfillment, excessive painlessness, existential certitude, material wealth, and all variety of romantic stimulation, we were just grateful for every day that didn’t involve getting eaten by a bear?”

On the song “Things That Would Have Been Helpful to Know Before the Revolution,” Father John Misty depicts the destruction of hierarchy to be reborn only out of our inherent need for convenience.

On every song, he lifts the curtain of some noble virtue to reveal the irredeemably flawed human behind it, going beyond moral relativism to pure denial of morality’s existence. On the song “Two Wildly Different Perspectives,” Father John Misty sings, “One side says ‘Y’all go to hell’ / The other says ‘If I believed in God, I’d send you there’ / But either way we make some space / In the hell that we create.” “Pure Comedy” is a benchmark in sweetly crooned nihilism that reflects both the society and individual we least wanted to see.

While Arcade Fire’s “Everything Now” does its share of finger wagging, the group conveys an overwhelming tone of indifference, a dramatic shift for a band that in the past could only be faulted for being overly earnest or melodramatic. Scarcely a critic could help but comment on the calloused way they handle the subject matter of a fan putting on their first record before killing themselves on the song “Creature Comforts.” This is truly the first time they take on the role of contemptuous rock stars, far removed from the orphans in a snowy parable they embodied on that 2004 LP. They conclude the song with, “We’re the bones under your feet / The white lie of American prosperity / We wanna dance but we can’t feel the beat / I’m a liar, don’t doubt my sincerity.”

Kendrick Lamar has always been an empowering figure who often addressed social injustice but in the past offered solutions and ways to stay positive. His new album, “DAMN,” opens with a story of him attempting to help a blind woman find something she has lost, who inexplicably kills him in return. This skit serves as an excellent summary for the fatalism throughout “DAMN.”

Where “To Pimp a Butterfly” attacks systems of oppression head on, here they are viewed as a mechanism of punishment carried out by God, which would make any attempt to fight this oppression futile. This makes several specific references to Deuteronomy in the Old Testament and God’s curse upon oppressed minorities. This is a bleak shift in message that has left many fans and critics feeling let down.

The album closes with the song “Duckworth,” which tells the story of his father Ducky’s past with Kendrick’s label owner (Top Dawg) when Ducky was an employee at a KFC that Top Dawg planned to rob. Ducky was aware of this looming threat and did whatever he could to get on Top Dawg’s good side, preventing the robbery and potentially saving his own life in the process. Kendrick Lamar concludes, “Whoever thought the greatest rapper would be from coincidence / because if Anthony killed Ducky, Top Dawg could be servin’ life / while I’d grow up without a father and die in a gunfight.” The tone here is more optimistic in a sense but told from Kendrick’s point of view still carries on the themes of chance, powerlessness, and unpredictability.

To the listening public, the views expressed by these artists may seem damning, but they may give us more than we perceive. It’s easy to prey upon our emotions and tell us what we want to hear. Whether from a musician or a political candidate, the lies we ask for can be the most profitable answer.

Telling the truth, however — even a depressing one — can bring us closer together and ultimately lead to real solutions rather than propel us toward something reactionary and empty. By expressing their hopelessness, musicians have disobeyed a public calling for fake messiahs and have revealed themselves as humans in our same predicament, facing our same doubts. Maybe weaning the public off its addiction to grandiose, unfulfillable promises is what we need most right now.

Articles related to “Trump-era defeatism”

Mudslinging, smear campaigns, and why I haven’t attacked Donald Trump

Album Review: Jason Isbell and his Nashville sound are older, better