The Utah Firefighters calendar for 2016 would make a great holiday gift. For a mere $20, you, too, can own a calendar that boasts pictures of baby-oiled, muscle-bound, spray-tanned men who for some inexplicable reason are wearing no shirts. And their bulky-looking firefighter pants are, well, resting somewhere just suggestively south of where they are normally worn. The proceeds for the sales of the calendar go to the American Cancer Society, which is a worthy cause, of course, but I’d consider buying one even if the proceeds went to Donald Trump. Why? Because it’s fun to look at.

“Is the calendar an example of reverse sexism?” I wondered, as I studied the professionally staged photos that grace each month’s page. Shouldn’t I be ready to saddle up and charge off to battle against any instrument that reduces the humanity of a person to a steamy picture? I’m a feminist, after all. This blatant display of sexual come-on should offend my sensibilities, shouldn’t it?

Hell no! Given the backdrop provided by the tragic events of the last few weeks some good fun, even if it tilts slightly toward the prurient, is nothing more or less than a chance to experience a moment or two of relief. We can all stop holding our breath, waiting for the next bomb to explode or some nutcase to grab a gun and start shooting, even if only for the length of time it takes to flip through the pages of a calendar.

Moreover, the prototypical image of a female pin-up girl emerged at the end of the 19th century as a break-out response to the repression of women in the Victorian era. My outrage should be tempered by that, I suppose. Up to that point, women were marginalized in the depictions of their lives. In the 1890s, however, Parisian artist Jules Cheret touched off the pin-up movement by convincing advertisers to feature young, voluptuous women, captured in moments of independent action, in their posters and magazines. The images Cheret created caught on because of their novelty. They appealed particularly to women who enjoyed seeing themselves as something other than stick figures laced up in corsets and crinoline, propped in a corner.

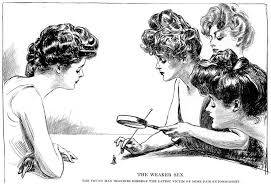

The pin-up spark jumped the pond, like wildfire some would say (come on, we are talking firefighters here). in 1895. Charles Dana Gibson, an illustrator for Life magazine, shook up women’s fashion with his cover illustrations of bosomy women with hourglass figures, dark piles of hair, and full, luscious lips. From this sprang the image of the “Gibson Girl,” and women in the United States became ultimately as enthralled as their European sisters had been with the work of Cheret.

The pin-up spark jumped the pond, like wildfire some would say (come on, we are talking firefighters here). in 1895. Charles Dana Gibson, an illustrator for Life magazine, shook up women’s fashion with his cover illustrations of bosomy women with hourglass figures, dark piles of hair, and full, luscious lips. From this sprang the image of the “Gibson Girl,” and women in the United States became ultimately as enthralled as their European sisters had been with the work of Cheret.

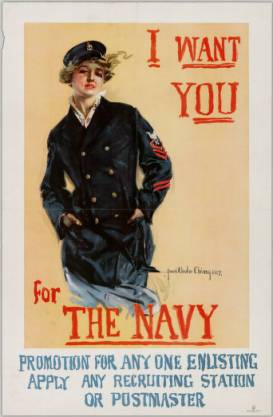

By the time the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, the value of the eye-catching Gibson Girl-like figure was widely recognized. The war department put it to use as a nearly ubiquitous image in their recruiting material. Posters appeared nearly overnight with pretty women often dressed in military uniforms urging their guys to enlist. “Gee, I Wish I was a Man. I’d join the Navy”, one blonde intoned. Another was more direct: “Just Do It.” I’ll admit, the former chafed my anti-feminist antennae more than a little, but I’m forced to remind myself of the times. There were few women in the armed forces.

By the time the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, the value of the eye-catching Gibson Girl-like figure was widely recognized. The war department put it to use as a nearly ubiquitous image in their recruiting material. Posters appeared nearly overnight with pretty women often dressed in military uniforms urging their guys to enlist. “Gee, I Wish I was a Man. I’d join the Navy”, one blonde intoned. Another was more direct: “Just Do It.” I’ll admit, the former chafed my anti-feminist antennae more than a little, but I’m forced to remind myself of the times. There were few women in the armed forces.

By World War II, the pin-up had been appropriated by the U.S. government not only as a recruiting tool (remember the sweetheart you’ll come home to) but also to induce the citizenry to ante up and buy war bonds. Rita Hayworth in 1941 (in a negligee with a black, lacy bodice) and Betty Grable in 1943 (in a tight swimsuit gazing over her shoulder with a come-hither twinkle in her eyes) were the two posters most requested by the GIs overseas.

One might ask, as I did, if there was a similar history for the male pin-up. My conclusion after some digging is not so much. I could find no parallel development of the male image in advertising, recruitment, or modeling. Rather, the overwhelming majority of the my search results made my eyes pop. They didn’t just tilt to the prurient: they dove right in and wallowed there. Even the earliest examples of hunky male calendars I could find on eBay were from 1960, long after pin-up girls had become iconic.

So what conclusions should we draw? I’m certain that some of the answer lies in the differences between how men and women respond to visual images. Women tend to be drawn more to nuance while the male eye favors directness. Even though there has never been a shortage of images that portray women as sexual objects, the pin-up has always been of a different ilk and directed at a audience. It sent a different message. It was subtle and designed to appeal to women who were beginning to intuit their personal power and to men who were drawn those women.

It seems also true that the phenomenon of the female pin-up, which has a history of development that reaches back into the 19th century, has benefited from the tinkerings and revisions made to it by those who employed it. The female pin-up has evolved over time, but certain constants have remained fixed. The images are flirty and curvy but with an air of steely independence.

There is a convergence, then, between the history of the pin-up calendar and the relatively recent emergence of the hunky calendar. Both rely on sex-selling to advance worthy causes. And both, while flirting with the obvious, stop short of being obnoxious. Coming from far different roots, it seems that their purposes have begun to overlap.

So, in the end, the Utah Firefighters Calendar may simply be an example of the progress we’ve made. In 2015, an organization as commendable as the American Cancer Society is counting on women to step up and fork over the money in a show of support. Whether women are drawn to donate by the cause or by the pages of the calendar really doesn’t matter much.

For me? I just think it’s fun.