He’s Neil young, right? Like the Jesus Christ of political rock music, he can do no wrong.

Well, sort of.

This album deserves not five but six stars for it’s intention, but it struggles to earn even three or four by its musical merit. The lyrics are largely junk as well, but to be even-handed about it, the lyrics aren’t meant to be poetic: this is an album of rallying cries, not dainty sonnets. Rather than honor the rules of a rigged game, Young rips off the fencing mask and goes for the jugular—ferociously, if somewhat ungracefully.

The consensus gripe among mixed reviews is that Young’s execution is clumsy, which is a valid observation, but otherwise most reviewers seem to feel implicated by its message. Furthermore, the ironic intent of “Rockin’ in the Free World” was lost on many, who erroneously seemed to think the song suggested that the world is free and we should rock on (including Donald Trump, who pissed off Young by using his song during Trump’s hilarious presidential campaign). For all we know, Young simply decided to dispense with metaphor and say it like it is.

Young is still throwing his old bones into the mill of imperialist capitalism full force, and he’s simultaneously rocking as hard as some half his age. Young is no stranger to the protest album. There was 2003’s environmental heads-up, “Greendale”; 2006’s anti-Bush foreign policy critique, “Living With War”; and 2009’s “Fork In The Road,” whose topic was fossil fuels. His song, “Ohio,” about the Kent State massacre, was one of the best contemporary examples of an effective protest song. What keeps Young young isn’t just organic, non-GMO produce; throw in a healthy dose of righteous indignation and hone that down to a focused laser beam of life purpose, and you’ve got a 69-year-old ass-kicking machine that still runs like an old Chevy. His distinctive voice is slowly getting older, and by any other standards some of the vocals on this album would be describes as “pretty bad,” but his guitar chops are solid as ever.

Joining him in the studio is Promise of the Real, a band fronted by Willie Nelson’s son, Lukas, and including—for this album—Lukas’ brother, Micah. These guys are almost as gritty as Crazy Horse, and what they lack in jangle or laxity (which isn’t much) they compensate for with finesse, and for some of the more musically stale songs, they are the saving grace.

Listeners who don’t know what Monsanto is will be scared and likely scurry away when the rock they’ve hidden under for decades is lifted up. But this review isn’t about the numerous crimes against humanity that this corporation has committed, the political corruption that follows in its wake, or the lives lost or destroyed directly and indirectly. That topic would warrant writing a very large book, not an article. Suffice to say that to those who consider themselves to be patriots or a decent human beings by any means, Monsanto is their enemy. Likewise, anyone who has no problem with Monsanto might be a vampire or a sociopath, and can consider this album a personal “fuck you.”

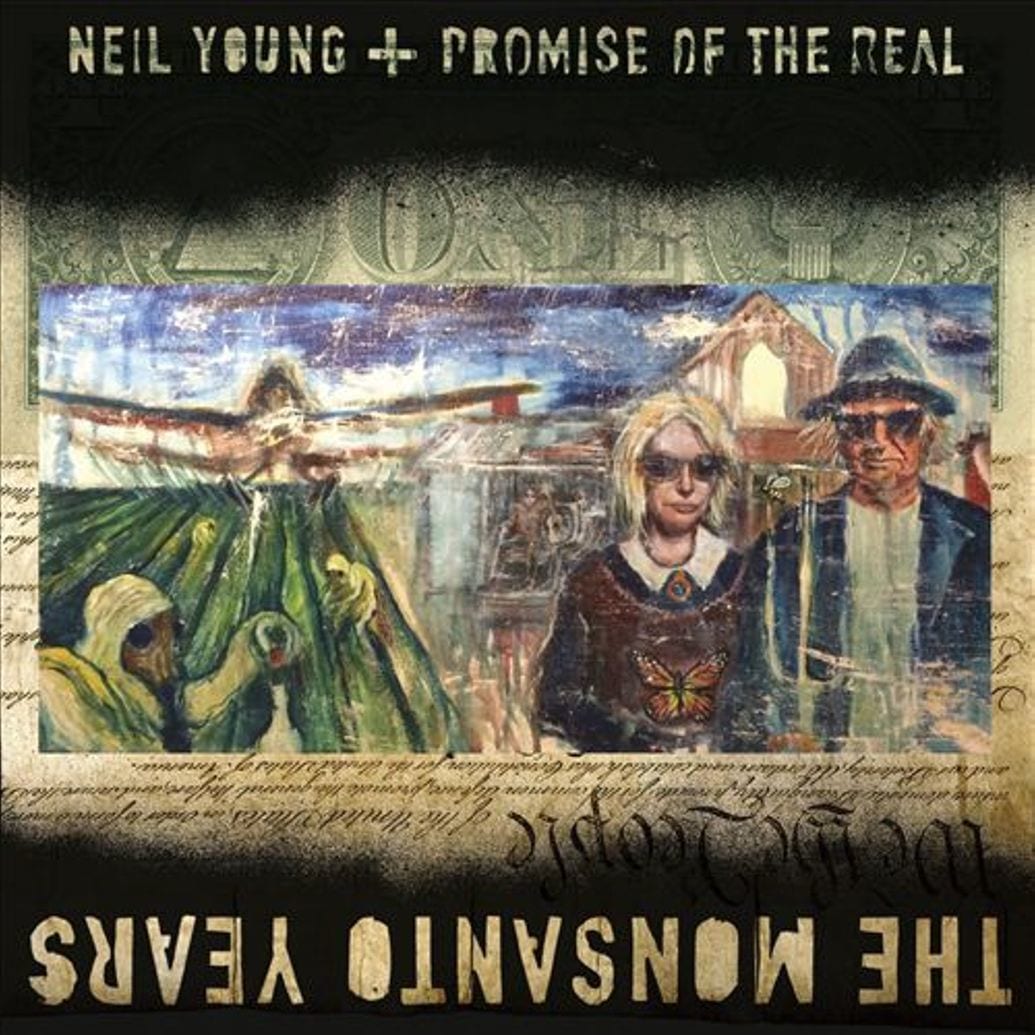

At any rate, Neil Young’s “The Monsanto Years” is socially educational in the tradition of Woody Guthrie, Johnny Cash, and Bob Dylan. It’s tempting to simply cut and paste the lyrics from the entire album, step back, and say “that.” But the cover art pretty well sums it up: a 2015 parody of “American Gothic” next to a picture of a plane spraying poison onto a field populated by ghostly and alien-looking workers in protective, full-body attire superimposed atop an upside-down U.S. Constitution and the back of a dollar bill. The only thing missing is Hugh Grant and Robert Shapiro hanging from upside-down crosses. Prepare yourself for a rambling folk-rock odyssey replete with political one-liners and corporate condemnation.

“A New Day for Love” echoes a modern maxim, announcing that “It’s a bad day to do nothin’.” As if recalling that honey attracts more flies than vinegar, this optimistic anthem suggests that hope isn’t lost. While Young condemns greed and war, the band slowly rocks, and the song ends out over the repeated chorus, “It’s a new day for love” while Young says just as much through a guitar solo.

More of a general expression of gratitude that feels to be more from a First Nations perspective than that of even the earliest political folk music, “Wolf Moon” could have appeared on a variety of Young’s other 34 albums. The subtext is climate change (or global warming—whatever you choose to call it, Rick Scott will be angry), and it’s one of the best tracks. Young and his guitar could stand alone, but the gentle accompaniment is just dirty and rustic enough without being obtrusive.

“People Want to Hear About Love” begins a procession of songs that sound fairly similar. Custom-crafted for concert singalongability, the chorus is featured heavily with plenty of room for instrumental work, including extensive call-and-response between guitars. The theme, to paraphrase, is basically “Gosh, this place is a bummer and we’re sick of hearing about everything that’s going wrong, is there anything nice to sing about?” However, the other interpretation is that the public is relatively callous when it comes to not wanting to be bothered. Young touches upon “Chevron millions going to the pipeline politicians,” “beautiful fish in the deep blue sea, dyin’,” “the corporations hijacking all your rights,” “world poverty,” and how “Citizens United has killed democracy,” “pesticides are causing autistic children,” and “people don’t vote because they don’t trust the candidates.”

Hopefully, residents of southern Utah will pause and consider “Big Box,” which is partially about the destruction of the small businesses that communities were built upon:

Main Street’s boarded up now the whole town’s asleep

The mom ‘n pop got boarded up, a small business retreat

Sprayed windows and broken glass, another car on the street

Out at the big box store people lined up for more

People working part-time at Walmart

Never get the benefits for sure

Why not make it to full time at Walmart?

Still standing by for the call to work

You hear that, local Chambers of Commerce? Hear that, complacent box store consumers? Neil Young thinks that you suck. This song should be played at every farmers market in the region every week.

“A Rock Star bucks a Coffee Shop” was originally titled, “Rock Starbucks.” This invasive species is the new McDonalds: even the sociological concept of “McDonaldization” itself has been reconsidered with the rise of Starbucks. Angry about Monsanto‘s legal efforts to block GMO labeling during the Vermont GMO-labeling controversy (and Starbucks’ tacit alliance with Monsanto through the Grocery Manufacturers Association), Young mentions that he doesn’t want to support biotech and big agribusiness just for a cup of coffee. He details how mothers deserve to know what’s in their children’s food, and how farmers have lost control of food: “When corporate control takes over the American farm / With fascist politicians and chemical giants walking arm in arm.” The story continues, as “Monsanto and Starbucks through the Grocery Manufacturers Alliance / They sued the state of Vermont to overturn the people’s will.” Eerie choruses of stretched out “Mooooonsaaaaantooooo” are something you probably never thought you’d hear.

Now for some real damned country music, none of that silly Luke Bryan crap. “Workin’ Man” is the story of Judge Clarence Thomas, who Monsanto had in their pocket and helped the company aggressively and unfairly destroy family farm after family farm. Musically, it’s a straight-up romp, and it’s amusing to imagine it blaring at a bar while cowboys, rednecks, and bluecollars raise their glasses of whiskey—produced from Monsanto’s Roundup Ready, Bt toxin-producing GMO corn.

“Rules of Change,” which rumbles and growls, is evidence of why Young is hailed as the “Godfather of Grunge.” Young champions the sovereignty of nature, arguing that it cannot be owned, and echoing Christ’s imperative (in the synoptic gospels) to “Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and unto God the things that are God’s.” His twist is to question what is Caesar’s with lines like “No-one owns the sacred seed / No man’s law can change that” and “Halls of justice got this wrong / Life cannot be owned.”

The title track, “The Monsanto Years,” is compositionally the most interesting, modulating in the middle for a guitar restatement of the vocal melody. It’s casual saunter is an ironic backdrop for the sad account of the status quo, with seeds made ready to tolerate being doused in chemical poisons, farmers with their backs against the wall, farmer’s children falling sick from the poisons, and grocers perpetuating the cycle by stocking the products made from GMO crops. What hit home the hardest are lines like “Family seeds they used to save were gifts from God, not Monsanto, Monsanto” and “Give us this day our daily bread and let us not go with Monsanto, Monsanto.”

The album leaves with “If I Don’t Know.” Finally, Young achieves a moment of actual poignancy. Sure, he talks about “a dam against the water so the river dies,” and “finding oil and shooting poison in the ground,” but as if coming back to lucidity after a lengthy anger-binge, this one has a lot of space, very little sermonizing, tons of guitar wailing, and an at least somewhat poetic refrain of “Veins, Earth’s blood.”

For an album that has taken a lot of flak from mainstream reviewers, it’s not that bad, though it ain’t going platinum. Young accomplished his goal, which was to be as loud a voice of reason as he could. He already has accumulated more laurels to rest upon than most musicians could accumulate through multiple lifetimes, so with nothing to prove and nothing to hide, he has carte blanche to say and do what he pleases. As a protest album, it shines, but as music—as “a Neil Young album”—it certainly has its moments but overall falls short of the glory of “Harvest Moon.”