Quagga mussels in Lake Powell pose threat to our water supply

Here’s a question for you. Do you want invasive, destructive, and prolific quagga mussels in your home’s plumbing, or would you prefer to use sustainable practices to use our local water resources to grow our area’s economy? I prefer the latter rather than paying billions for the proposed and risky Lake Powell Pipeline that would link us to Lake Powell — where quagga mussels already reside in great numbers and are increasing. I don’t know if the mussels would or could end up in our home plumbing, but I don’t want to find out.

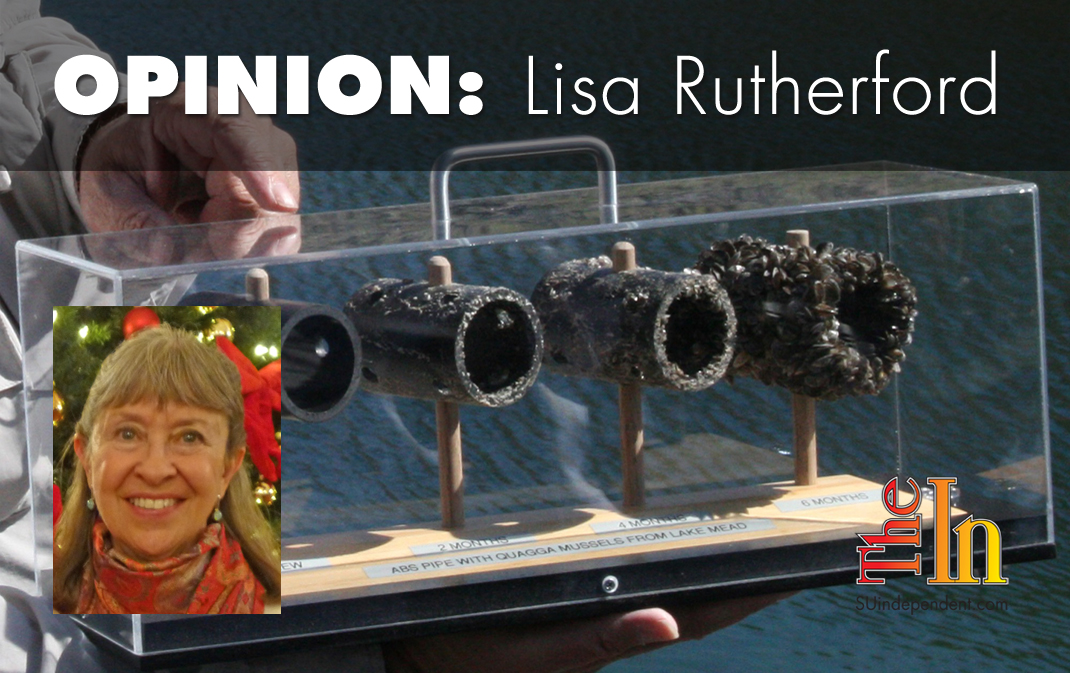

You’re probably asking, “Are quagga mussels really a problem?” A little searching revealed that they are. They have been a problem for a long time, and it’s getting worse – not better.

As far back as 1998, the Department of Interior’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service created the 100th Meridian Initiative to look into the matter and try to slow the westward spread of this and other invasive species, apparently with no real success. It was clear even then, as that report states, that the mussels can impact efficiency at water facilities, including flow restrictions; encourage rust on infrastructure; and damage the environment. The first quagga mussel west of the Continental Divide was discovered Jan. 6, 2007.

In the 2008, the Lake Powell Pipeline Proposed Study Plan submitted by the Utah Division of Water Resources — or UDWRe — to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the UDWRe acknowledged that quagga mussels and their counterpart, zebra mussels, were moving west with “The presence of an extremely small number of individual, larval quagga or zebra mussels in Lake Powell.” The first adult mussels were located on a houseboat on Lake Powell March 3, 2013.

In August 2013, Nathan Owens, the Aquatic Invasive Species program coordinator for the Utah Department of Natural Resources, reported that “The quagga situation in Lake Powell has worsened.” The department warned that mussels can plug even large-diameter water lines, resulting in millions of dollars to “try” to remove them, likely resulting in higher utility bills.

According to the National Park Service Glen Canyon website, in 2016, thousands of adult quagga mussels were already attached to canyon walls, the dam, boats, and other underwater structures. They expect that to increase.

In 2016, the National Park Service expressed concerns to the UDRWe about transferring water from Lake Powell — a known quagga mussel-infested water body — to another water body (Sand Hollow) unless “sufficient mitigation measures are in place.” The state responded that a combination of chemical treatment and self-cleaning microscreen filtration was planned, and if “more effective and reliable aquatic invasive species control measure are available when the Lake Powell Pipeline Project is designed prior to construction, then the best available technology will be designed and implemented, as long as such best available technology does not have adverse effects on environmental resources.” However, the UDWRe acknowledged that it “may not be possible to absolutely manage this potential problem to any practical extent for all species; however, the ability to monitor the problem is a critical factor.”

The state hopes to control the mussels using a molluscicide. Some who have used the product state in comments to FERC that “Our experience has been that the proposed molluscicide (i.e., Zequinox) does not have a 100% kill rate and filtering is not 100% effective.” So will taxpayer money spend on this be a wise decision? According to the NPS, more than $1 million a year has been spent on containment efforts since the infestation was first discovered. We see how effective that’s been.

In addition to the molluscicide, the state plans “physical” controls. But according to a fairly recent State of Michigan report, “Conventional water screens, in-line debris filters, ultrafiltration, and traveling screens, many of which are now becoming self-cleaning, can be effective in blocking adult mussels and shells, but many still allow passage of veligers.” Veliger is the mussel’s microscopic stage — a stage during which it can remain suspended in the water column for up to four weeks, easily passing through filters and strainers.

So much for Utah’s filtering idea.

The report adds that newer “antifouling” construction materials for structures and pipes “could minimize the mussels’ impact” along with toxic antifouling coatings that must be reapplied, but is that enough to reassure taxpayers who will be footing this ongoing and expensive bill.

The NPS also expressed concerns about the effects of Lake Powell Pipeline water on the Virgin River system. Although the Lake Powell Pipeline does not go directly to the Virgin River, the water would go from Lake Powell to Sand Hollow, to Quail Creek Reservoir and subsequently through releases from Quail Creek to the Virgin River. The NPS suggests that the impact cannot be entirely mitigated. Here is the state’s response to their concerns:

“If Sand Hollow Reservoir becomes infested, it would be necessary to implement treatment at the reservoir’s outlet structure to prevent colonization in the water system and its appurtenances. This would prevent any transfer to Quail Creek Reservoir. Should Quail Creek Reservoir become infested, treatment would be applied at its two outlet structures, the main dam and the south dam. At the same time, any discharges from the reservoir would be shut off. There are many levels of protection to protect the Virgin River from any aquatic invasive species infestation resulting from the LPP Project. Closing the outlet valve at Quail Creek Reservoir, combined with additional treatment, would completely address this issue.”

So they have a plan to keep mussels out of the Virgin River, but will the state’s plan prevail in a dire situation? Is it any better than earlier plans elsewhere that have failed to control these invasive creatures?

There have been some “partial” success stories in Utah with mussel eradication, such as Deer Creek Reservoir. In 2014, mussels were found in the reservoir, but as of July 2018, the Utah Department of Natural Resource announced they are gone. Unfortunately, the “current classification” as of March 2019 on the Official Mussel Infestation Report lists “suspected,” so the story is not over for Deer Creek either, or at least that’s how it’s reported. My point is that there’s much confusion about how to best control the species and exactly where the species is at this time.

I hope I’m making it clear to readers how complex and opaque this situation is. Perhaps the only thing that’s accurately known is the cost to areas that have had to deal with this. We don’t know what it might cost in the future, however, given that current treatment is not effective. Will future options be even more expensive?

In 2010, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that mussels cause $1 billion a year in damages to water infrastructure and industries in the U.S. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service stated in a 2012 fact sheet that if mussels were to invade the Columbia River, “they could cost hydroelectric facilities alone up to $250–300 million annually,” and that cost did not include environmental damages and other associated costs. “Annually, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation spends $250,000 on staff, $30,000 on equipment and $25,000 on publications related to zebra mussel prevention and control. The state will spend an additional $71,000 over 5 months to install new boat ramp monitors for zebra mussels.” And that was back in 2010. How much are they spending now?

Congressional researchers estimated that zebra mussels alone cost the power industry $3.1 billion in the 1993–99 period with their impact on industries, businesses, and communities estimated at more than $5 billion.

A 2010 Quagga-Zebra Mussel Action Plan for Western U.S. Waters warned that increased and immediate action was needed, and if not done, “irreparable ecological damage to western waters and long-term costs will be in the billions.” And that was a 2010 projection. Now, nearly ten years later, the situation has worsened, not improved.

Prior to that, in 2009, the Idaho Aquatic Nuisance Species Taskforce, following extensive research of existing databases and published research, provided cost estimates for mussel control in a variety of water situations, including drinking water intakes and irrigated agriculture. They did not include single-family home water facilities in their estimate, which amounted to $42,000 per water facility for 100 Idaho facilities. And again, that was 10 years ago.

The UDWRe November 2015 Draft Study Report 2 Aquatic Resources made it clear: “They have demonstrated the potential to both damage ecosystems and to require significant and costly, but often fruitless, investment to manage and control their effects on structures and equipment in the water supply industry.”

Utah’s Department of Natural Resources states, “We have been tasked with doing everything possible to keep quagga mussels contained in Lake Powell (as well as other infested waters outside of Utah) and out of the rest of the waters in the state.” In the meantime, Utah’s UDWRe is working feverishly to move water from infested Lake Powell to Sand Hollow. A conundrum, indeed!

The 2018 Strategy to Advance Management of Invasive Zebra and Quagga Mussels reminds us that this mussel battle has been ongoing for 30 years, and most has been reactive and focused on preventing further spread to utilities and industrial facilities. Yet prevention seems to elude us.

With the quagga mussel situation in Lake Powell worsening, as has been acknowledged by Utah Department of Natural Resource, and with our limited knowledge and ongoing efforts to get our arms around this invasive species, we should be very wary of proceeding with the Lake Powell Pipeline Project. The project was conceived in the mid ‘90s, when fears about the spread of mussels were growing but nothing like today. Now leaders know more and should be more concerned about transporting these creatures our way.

It’s interesting to note that the state’s March 2011 Draft Study Report 2 Aquatic Resources to FERC devoted about 10 pages to the quagga mussel issue and the Nov. 2015 Draft Study Report 11 Special Status Aquatic Species and Habitats devoted only one paragraph to the quagga mussel situation while the April 2016 Final Study Report Aquatic Resources devoted extensive coverage to the issue. A third of the 2016 107-page document is devoted to the quagga mussel issue and efforts to control them. Obviously, this has become a much more serious problem since this project began.

My original question was, “Do you want invasive and prolific quagga mussels in your home’s plumbing or would you prefer to use sustainable practices to use our local water resources to grow our area’s economy?”

Again, I don’t know if the mussels would ever make it into our plumbing, but with everything I’ve read about the species and their ability to move across the nation, even with prevention methods employed, I would not want to bet against them — certainly not when we have enough water to grow our area and support over 500,000 people and a multi-billion dollar project facing us.

The viewpoints expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Independent.

How to submit an article, guest opinion piece, or letter to the editor to The Independent

Do you have something to say? Want your voice to be heard by thousands of readers? Send The Independent your letter to the editor or guest opinion piece. All submissions will be considered for publication by our editorial staff. If your letter or editorial is accepted, it will run on suindependent.com, and we’ll promote it through all of our social media channels. We may even decide to include it in our monthly print edition. Just follow our simple submission guidelines and make your voice heard:

—Submissions should be between 300 and 1,500 words.

—Submissions must be sent to editor@infowest.com as a .doc, .docx, .txt, or .rtf file.

—The subject line of the email containing your submission should read “Letter to the editor.”

—Attach your name to both the email and the document file (we don’t run anonymous letters).

—If you have a photo or image you’d like us to use and it’s in .jpg format, at least 1200 X 754 pixels large, and your intellectual property (you own the copyright), feel free to attach it as well, though we reserve the right to choose a different image.

—If you are on Twitter and would like a shout-out when your piece or letter is published, include that in your correspondence and we’ll give you a mention at the time of publication.

Articles related to “Quagga mussels in Lake Powell pose threat to our water supply”

Five additional resources to help in the fight against invasive quagga mussels