U.S. Congressman John F. Lacey said in 1901, “The immensity of man’s power to destroy imposes a responsibility to preserve.” This was the prelude to the Antiquities Act that the Iowa congressman sponsored and put before Congress and ultimately saw enacted into law in 1906. Lacey was a Civil War veteran who had seen firsthand the destruction perpetrated by man against man, but he also lived during the heyday of man against nature, when wildlife such as bison and the passenger pigeon were being hunted to extinction and the West was not only open to expansion but to wanton greed for resources such as timber and minerals, but also for ancient artifacts of American antiquity.

While these places and artifacts belonged to native tribes and peoples, they had no voice in the discussion taking place between the European-American factions discussing their fate. The landscapes that held their stories, sacred sites, histories, and surviving culture would be determined by greedy businessmen, hungry ranchers, worried anthropologists, determined educators, and warring politicians. What was happening across the Southwest, whether intentionally or not, was the whitewashing or cultural cleansing of pre-settlement history as sites and artifacts were looted and sold to the highest bidder.

Regimes throughout history have sought to wipe out the memory, beliefs, and histories of opposing cultures and ethnicities through book burnings or destruction of cultural and historical sites, thereby making the destruction of their opposition complete. To destroy places, writings, and texts not only destroyed the physical existence of these cultures but also their cultural knowledge. German Nazis and the Taliban in the Middle East offer a couple of examples. It became such a problem during World War II that in 1954 the U.N. adopted the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict to protect cultural heritage. They explain that cultural heritage reflects the life of the community, its history, and its identity. Its preservation helps to rebuild broken communities, re-establish their identities, and link their past with their present and future.

While no one here in America is engaging in intentional cultural cleansing, our history with Native Americans is well-known and documented. Our actions have bespoken an arrogance and preference for our own history over theirs, or even worse, the seizure and ownership of their history as our own, using it for prestige or profit. Like putting a new coat of paint across a mural, we have been writing over the rich history of those who came before us, and thereby in small measure erasing their presence and cultural identity.

Despite the reality of the spoils of conquest, where we said, “This is now mine,” we eventually embraced a more communal view of natural resources and lands with the designation of public lands for the use and enjoyment of all Americans as a national heritage and birthright.

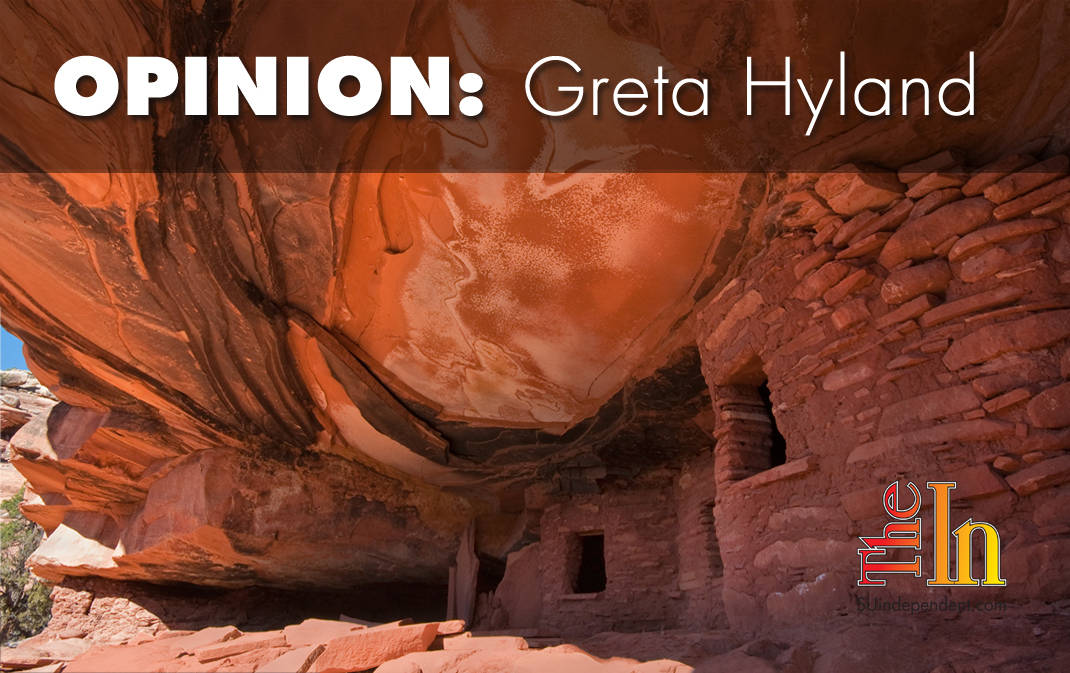

The designation of Bears Ears National Monument was an historic event, not just in terms of designating the monument but in terms of healing broken relationships and a scattered and broken past. Allowing Native Americans to co-manage the monument and have a say in the destiny of their homeland and history not only enables them to reconnect to their past but in a significant way allows them to join in the present and move into the future with the rest of Americans as equals.

With a reconvening Congress meeting under new leadership and power, the ever insidious threats to the Antiquities Act and the rich heritage public lands provide is as imperiled as ever. If Congress succeeds in disposing of public lands or undoing the designation of Bears Ears National Monument, it will not only be a slap in the face to Native Americans who have long been waiting to be treated with dignity and respect but a slap in the face to all of us who share in the communal access public lands afford. Those landscapes now hold our shared cultural heritage and our identity as well.

Despite his valiant efforts and success at getting the Antiquities Act passed, Lacey’s game and bird law came too late to save the passenger pigeon, with the death of the last bird marking the species extinction in 1914. It was a stunning symbol of the squandering of America’s natural bounty. In a speech to the League of American Sportsmen in 1901, Lacey revealed the depth of his concerns about such waste and misuse of natural resources — about, as he put it, mankind’s “omnidestructive” ways — wherein he warned that if the destruction was allowed to continue, the world would “become as useless as a sucked orange.”

If we are not vigilant, we may live to see the extinction not only of the Antiquities Act, but the extinction of our access to public lands and the natural bounty they still hold in wildlife, recreation, solitude, beauty, healing, and history. We may also let the opportunity pass to lock arms with our Native American brothers and sisters and create a shared future.

Greta Hyland has a master’s degree in environmental policy and management and is an advocate for public lands, smart and sustainable use of resources, and people most impacted by the effects of industrialization in the global market. She lives in the Southwest and is an avid reader, trail runner, and beer drinker.

Articles related to “Between uncertainty and fragility: The imperiled Antiquities Act”

Black Diamond and Patagonia take a stand on Utah public lands