|

| “Manual Conjuring” |

Written by Don Gilman

|

| “Red Hare” and “White Hare” |

The big jackrabbit stepped out from the sage, its nose sniffing, whiskers twitching. Its eyes darted nervously. The critter seemed ready to zip back into the sheltering bush, but it was too late. The boy had it squarely in the gunsight of the Remington .22. His grip was steady, and his aim was true.

He pulled the trigger.

Russell Wrankle was that boy, scrambling around in the California desert near Palm Springs, a hunter of rabbits, a harvester of furs. He spent countless hours stalking the lagomorphs, collecting their pelts, intending to sell them to a furrier.

“I’d kill these rabbits and then skin them, because I wanted to be an ethical killer,” Wrankle said. “In my youthful naiveté I thought I could sell the rabbits to a fur trader for the pelts.”

His father was a gardener, and his client list read like a Hollywood who’s who: Steve McQueen, Ally McGraw, Barry Manilow, and Liberace. Wrankle often mowed the lawns of these famous clients, and he had an assumption that he, too, would end up in a blue-collar career. He was raised to believe that masculinity and manual labor were intimately intertwined.

|

| “Dangling Amphibian” |

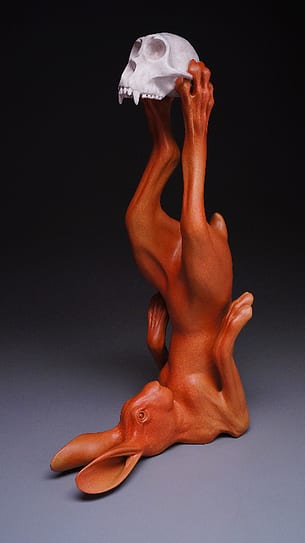

These days, Wrankle, 51, does work with his hands as a professional sculptor, bringing those rabbits to life in strange and surreal ways. There are rabbits reclining, looking relaxed and poised. A rabbit in a yogic shoulder stand, a monkey’s skull balanced on its feet. Rabbits partially skinned, their fur stretched over human hands and other objects.

Wrankle is also a full-time assistant professor of art at Southern Utah University.

A class in ceramics changed his viewpoint forever. From that point, college beckoned, and the transformation from the blue-collar boy into the educated man began, something that his parents did not fully understand.

“They didn’t really get it,” Wrankle recalls. “That’s fine. [My father] was of that thought that education was elitist. I remember coming home being an elitist. You go to school your first year and you come home and think you know everything, and your parents don’t know anything.”

His parents did not fully comprehend his art.

“My parents don’t get it,” Wrankle said. “I didn’t work too hard to make them get it. My dad came here a few times before he died, and he would say ‘Why don’t you make something happy?’”

Wrankle does not limit himself to rabbits. There are dogs, frogs, and masks. Dogs with crabs coming out of their mouths, a crab claw pinching a brain. It is a dreamlike world that Wrankle creates—beautiful and occasionally disturbing. His work does not appeal to everyone, but for some, his work approaches genius.

Susan Harris, professor of art and design in ceramics at Southern Utah University, believes that Wrankle’s work is unique.

|

“I think his work is splendidly crafted and can be appreciated on many levels, although some pieces may seem enigmatic to the average viewer,” Harris said. “I can’t think of anyone whose work resembles Russell’s. [I have] admiration for his willingness to take risks in his work and to continually work in new directions with difficult ideas.”

Wrankle recalls a lunch with Harris. His father had died the week before, and he and Harris were discussing the loss of a parent.

“She said, ‘What do those rabbits mean anyway?’ and I replied, ‘Sex.’ I was referring back to the cross-cultural meanings of fertility, cycles of the moon, and without missing a beat, she said, ‘Sex is a good anecdote for death.’”

“It’s true, and I’ve started thinking about that more,” Wrankle said. “There’s an artist named Joe Bova [who said] ‘Sex and art are the two things that create immortality’ because sex creates another person and art lives on, makes you immortal. Hopefully.”

|

| “Hare With Monkey Skull” |

The path to becoming a sculptor was a long and winding road. Wrankle attended Southern Illinois University, where he received his Master’s in Fine Arts. Eventually, the course of his life brought him to Toquerville, where he began selling pottery. While this decision was financially successful, it ultimately left him feeling unsatisfied.

“The pottery was just to make a living,” Wrankle said. “That’s easier to market. I decided my heart wasn’t in it. I just didn’t have time to do both. The one thing that keeps me up at night, excited about the next day, was sculpture.”

He has never looked back.

Wrankle’s process for creation is multi-faceted. He creates his work in a dusty studio behind his house in Toquerville.

“Well, I stress over it for a couple of months first, trying to figure out how to do it,” Wrankle said, laughing. “But in the end it’s just brute strength and ignorance. I just throw clay together and respond to it.”

A single sculpture can take up to 150 hours to create.

His work has been featured in galleries and art studios across the United States, and has sold many pieces to private art collectors. One local fan of his work is Shawn Ekker of Ekker Design and Build in Cedar City. As a designer of award-winning homes, Ekker has an appreciation for the form and beauty of Wrankle’s work. He recently purchased a piece and plans on displaying it prominently in his home.

“There was one I had my eye on for quite some time and the opportunity came up to buy it so I did,” Ekker said. “I wanted to get at least one of his pieces. It’s a dog’s head and it’s got a crab in its mouth. Artistically it’s really original which is important for art.”

|

| “Hold It” |

Ekker feels that Wrankle’s approach to art is unique and uncensored.

“It comes right from his brain. No filter. He just crafts what his brain conjures,” Ekker said. “[The] first time I saw it, I knew it was something special, it had some character, some personality. The more pieces of Russell’s work I saw, I understood his style. You can understand the context of his work. I like that about it. There a narrative that goes along with it.”

Ekker says the piece will have a special spot in his home.

“I’m building a showcase for sculptures in my home, and I’m going to construct a showcase for it. I’ve got a lot of art. I pick my favorites and display them in my house … Russell is one of my favorites right now.”

As a teacher, it is important for Wrankle that he continues to create art.

“Being an active artist, I have something to tell the students,” Wrankle said. “I’m not just a professor who shows up and teaches and gets a paycheck. I actually work as an artist. My colleagues are the same as me. You hear stories about teachers who start teach and stop making art. I didn’t want to be that guy.”

The road for Wrankle has been a long and winding one, from the desert of California to university in the Midwest and finally to the desert of southern Utah. From a blue-collar upbringing to college professor, from potter to sculptor, he has undergone a transformation from the hunter of rabbits to a creator of art. For Wrankle, however, one consistent factor will continue in his life: “The rabbit will remain, in one context or another.”