Our Geological Wonderland: A trip through the Virgin River Gorge

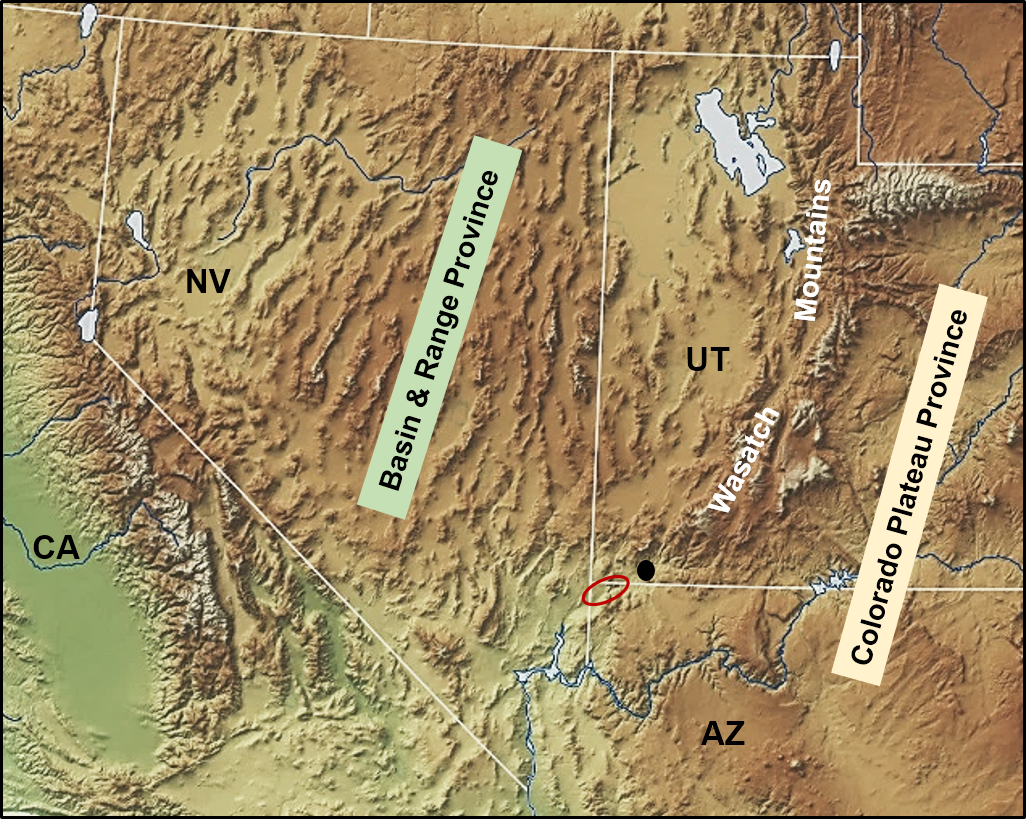

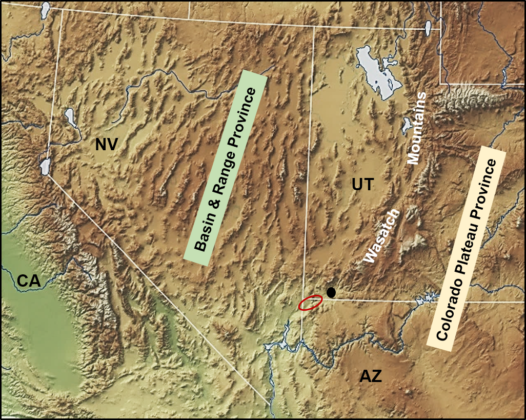

According to the Arizona Department of Transportation, approximately 23,000 vehicles travel through the impressive scenery of the Virgin River Gorge on Interstate 15 daily. Located in the northwestern corner of Arizona, the Virgin River Gorge can be considered with a modest dose of imagination to be a geological example of the rabbit hole in “Alice in Wonderland.” With even a passing interest, it becomes evident that there are major changes in the geography and geology from one end to the other. These changes are due to the fact that hiding in plain sight within the gorge is a major geologic province boundary. This boundary separates the Colorado Plateau Province on the east from the Basin and Range Province on the west (Figure 1). Significant differences in geographic and geologic features are a result of differences in the geologic history and the geologic processes that are operating below the surface of these two provinces. Exposed rocks visible in the gorge, however, provide “forensic” evidence for what is happening.

Overall regional setting

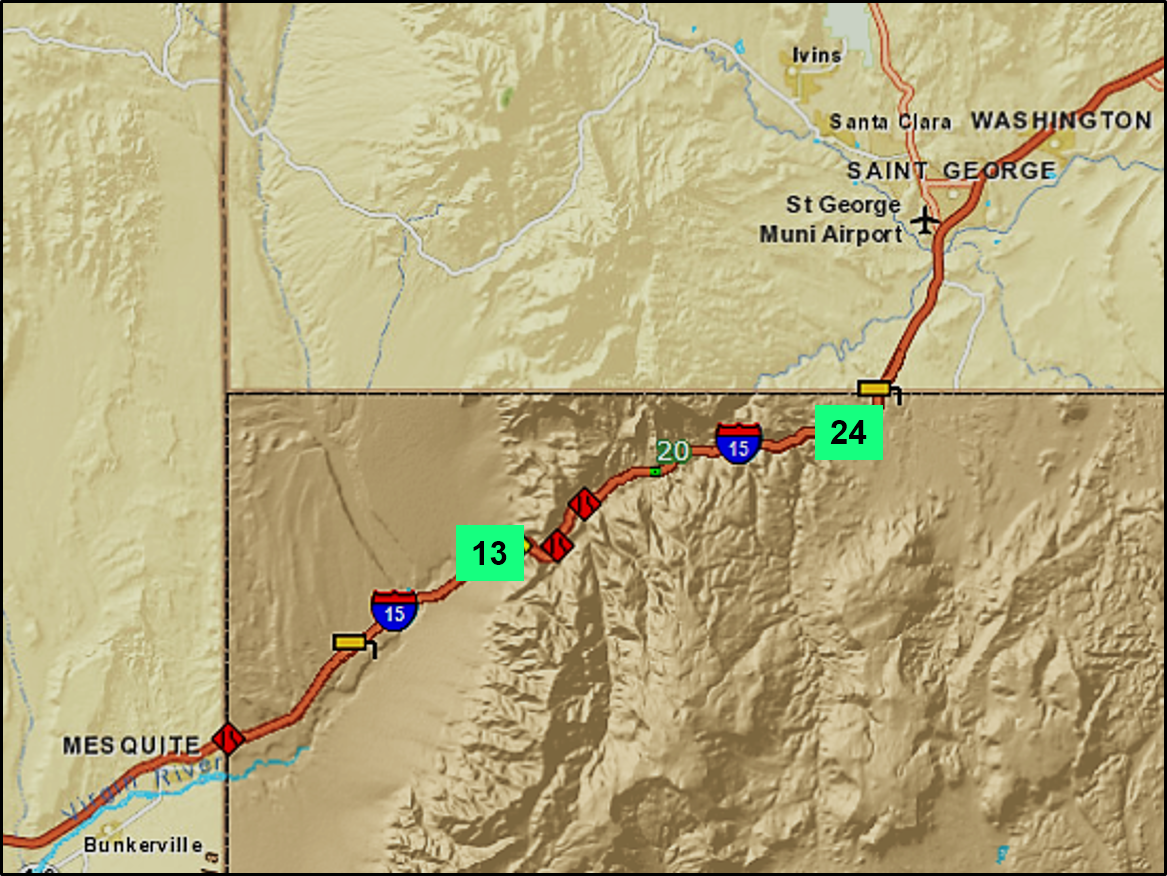

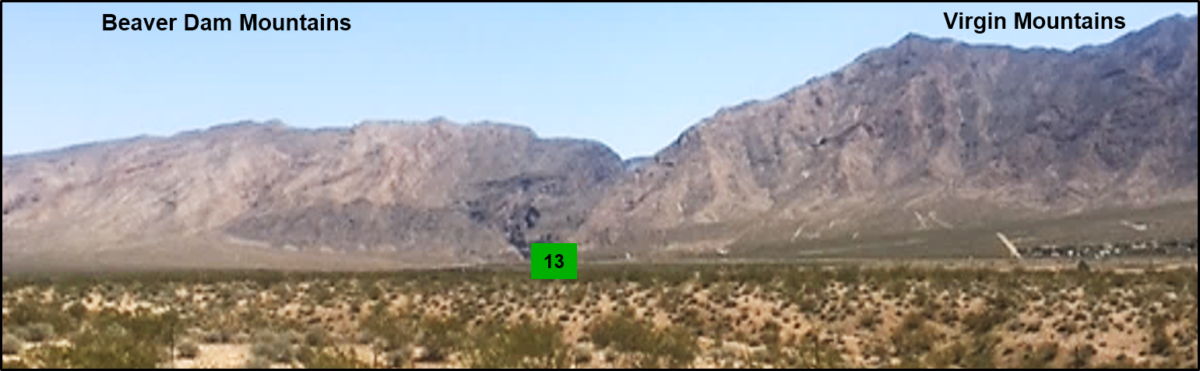

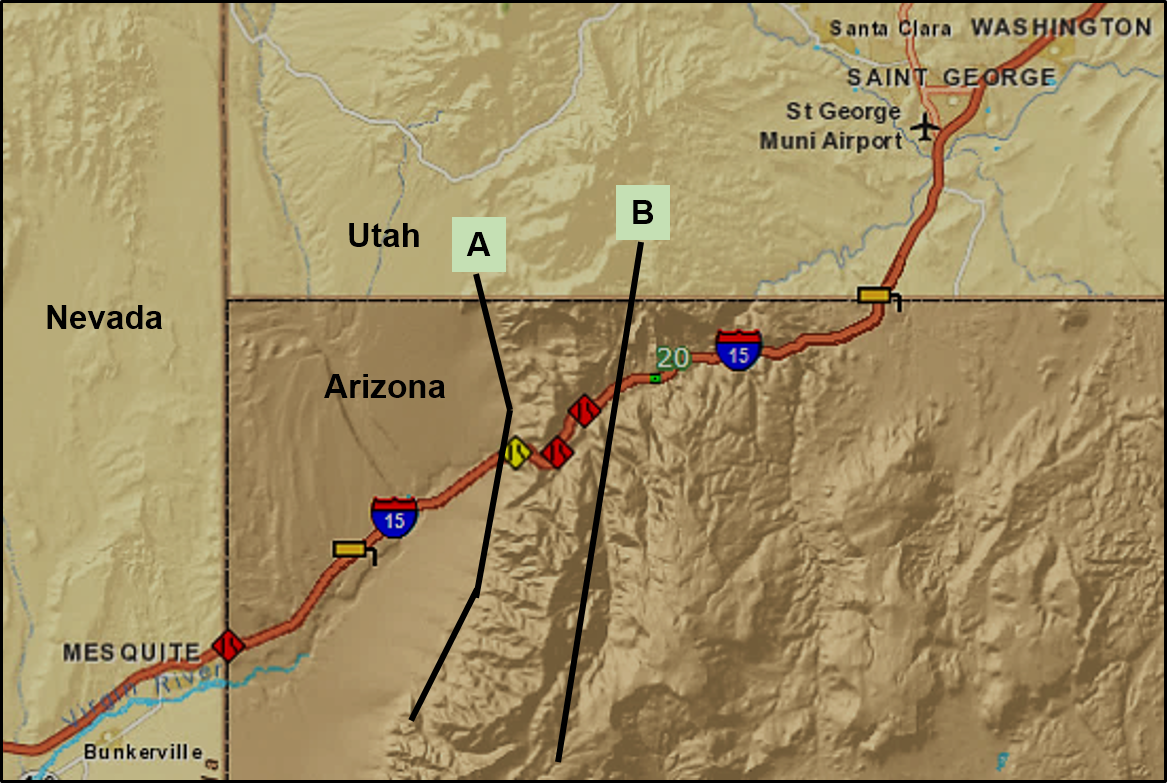

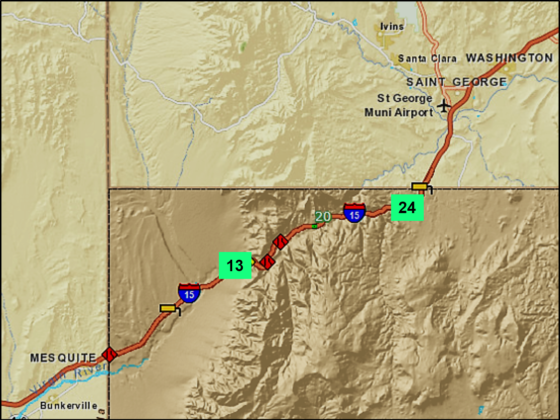

Heading northbound from Las Vegas on Interstate 15, the highway snakes across the desert with mountain ranges in the distance on either side (Basin and Range Province). Passing through Mesquite, the highway crosses mostly flat desert and heads directly towards a wall of mountains. Upon arriving at that wall, a cleft appears, through which the highway enters the Virgin River Gorge at mile marker 13 (Figure 2).

Heading southbound on the interstate through the colorful rocks of southern Utah and crossing into Arizona (Colorado Plateau Province), the highway heads towards the Beaver Dam Mountains and descends into the upper part of the Virgin River Gorge at mile marker 24 (Figure 2).

Some of the differences in the geology can be seen in the following two figures, which illustrate contrasts between the two entrances to the gorge (Figures 3 and 4).

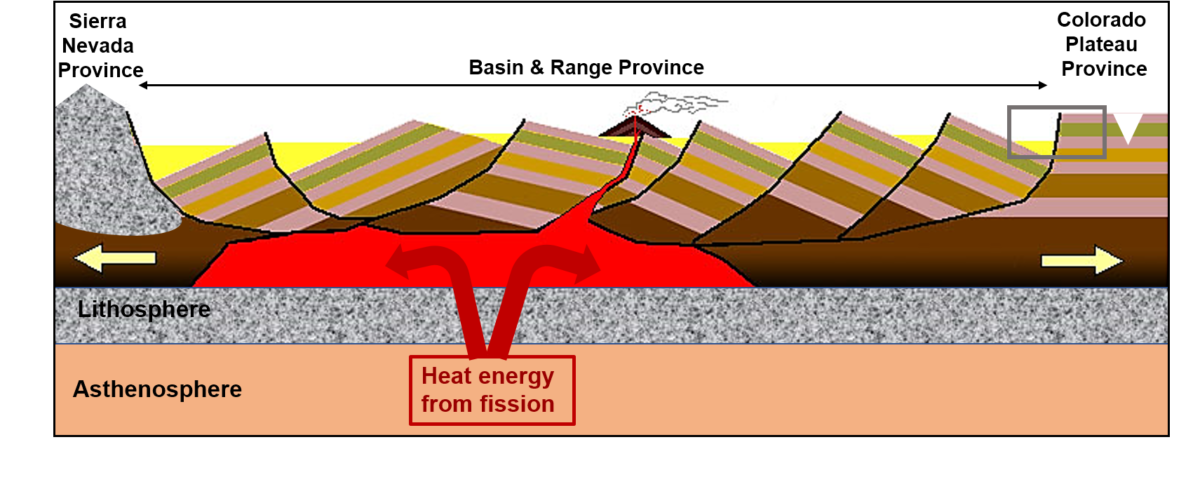

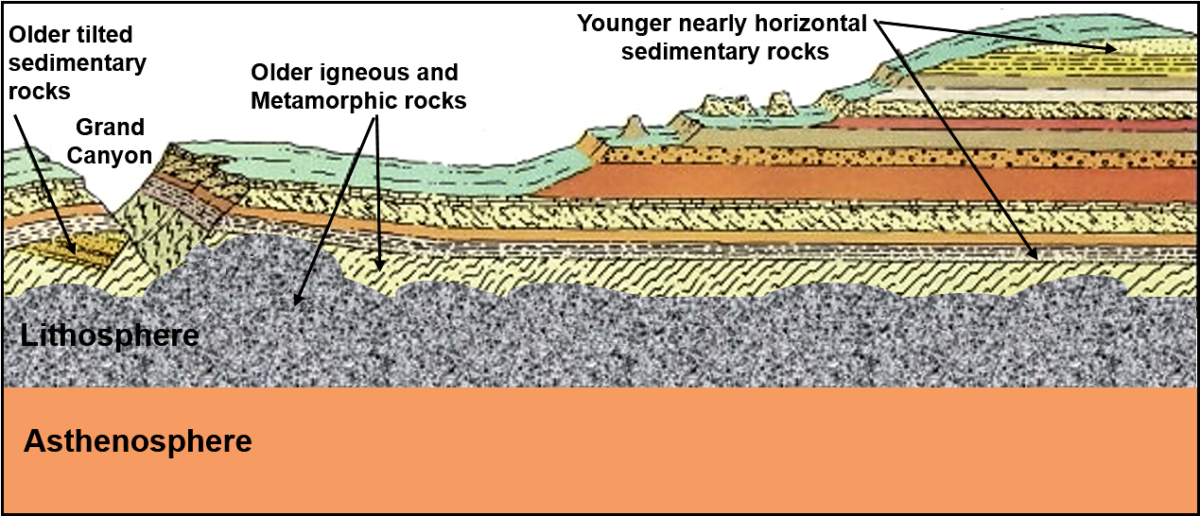

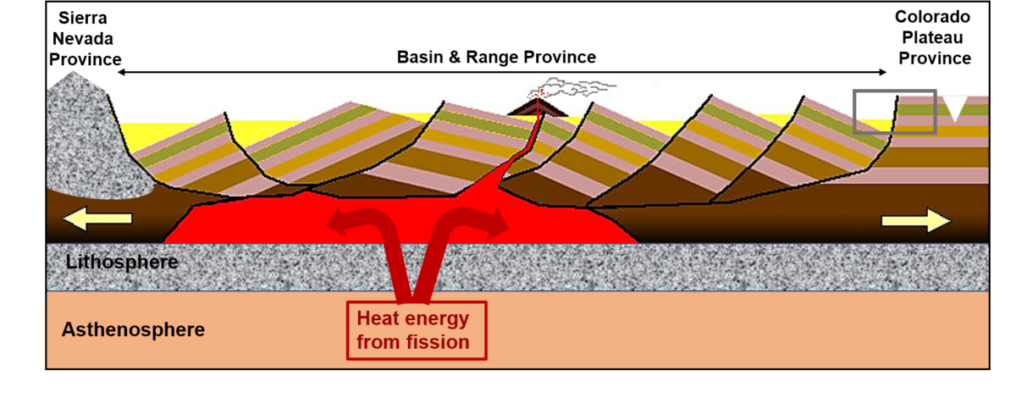

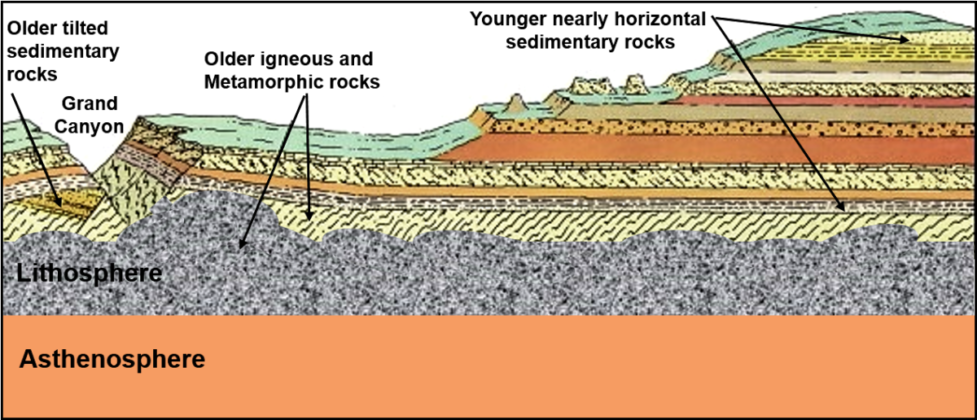

The following two figures illustrate some of the major differences between the Basin and Range Province (Figure 5) and Colorado Plateau Province (Figure 6). Distinct changes in topography, types of rocks, and structural features occur across the boundary, and these changes are what make a drive through the gorge like being in a scenic and geologic wonderland.

This province is literally being split apart by tension resulting from a source of heat energy (from nuclear fission) that exists below the region. Evidence for that heat is provided by numerous volcanoes and lava flows scattered throughout this province. The term “Basin and Range” comes from the generally parallel north-trending mountains (the ranges) separated by valleys (the basins). Rocks in each of these mountain ranges are tilted and bounded by faults and are thus described as fault block mountains. On a map such as Figure 1, these ranges were once aptly described by geologist Clarence Dutton as resembling “an army of caterpillars crawling northward.” Exposed rocks represent a wide range of geologic ages and rock types, and they are generally also distinctly tilted and faulted. These rocks can be seen in the lower, narrower, and steep-sided portions of the gorge (mile markers 13–18) and generally appear as tilted gray and brown weathering rocks.

In contrast, the Colorado Plateau consists of a broad, uplifted region with elevations reaching 11,000 feet. This plateau is dissected by rivers such as the Virgin River, the Green River, the Colorado River, and others. Within the upper portions of the gorge (mile markers 18–24), these rocks are generally only slightly tilted or nearly horizontal and appear gray, light brown, and red. As with the Basin and Range, exposed rocks represent a wide range of geologic ages and rock types, but they are generally less deformed or faulted.

On a regional scale, the relatively high elevation of the plateau, the generally horizontal nature of the rock layers, and downward erosion by various rivers have produced a wealth of scenic beauty that has been recognized by the establishment of many national parks and monuments such as the Grand Canyon, Zion Canyon, Bryce Canyon, Monument Valley, and others.

The boundary between these two provinces occurs as part of a major fault. This system is part of the Wasatch Fault System, and it is represented by a series of faults extending from Arizona up through Utah (along the Wasatch Front) and into Idaho. The province boundary itself is nicely exposed in the walls of the narrow gorge,

Taking the drive

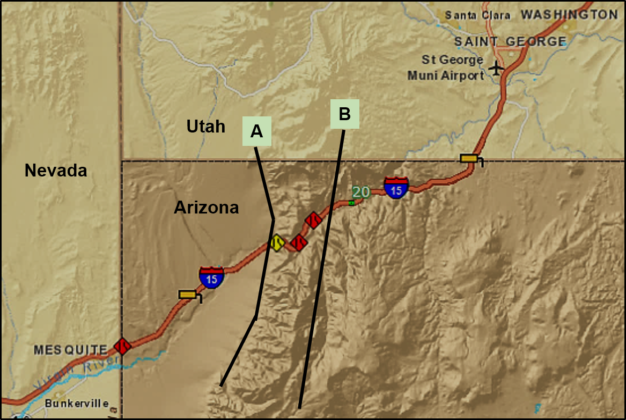

From the Arizona desert, the highway crosses a fault at the base of the mountains (Fault “A” on Figure 7), enters the Virgin River Gorge at mile marker 13, and then climbs to about mile marker 24. Abrupt changes in color, orientation, and geologic age of the rocks occurs along a fault (Fault “B” on Figure 7) that crosses the interstate between mile markers 17 and 19 (including Cedar Pocket, Exit 18). This fault marks the boundary between the Basin and Range and Colorado Plateau Provinces.

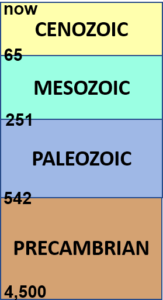

From mile marker 13 to mile marker 18, the narrow canyon of the gorge has steep walls that consist of Lower to Middle Paleozoic rocks (Figure 8). Rocks exposed in this part of the gorge are mostly limestone and dolostone deposited in warm, shallow seas that were widespread in this region during Early and Medial Paleozoic time. They are similar in lithology and age to rocks in the Death Valley region of California. Some layers have fossils of marine-dwelling invertebrates embedded within.

A very distinct change occurs at around mile marker 18. A good location to view this change would be on the overpass at the Cedar Pocket Exit 18. At this location, eroded canyons cut almost perpendicularly across the highway and are the result of another fault (fault “B” on Figure 7) that has allowed more distinct weathering and erosion of the rocks. The distinct changes in color and orientation of the rocks are evident in Figure 9.

From mile marker 18–24 — the upper portion of the gorge — the gorge becomes wider with less imposing cliffs. Exposed rocks include a variety of nearly horizontal and more colorful brown, grayish-brown, and red weathering rocks. These rocks include a variety of mudstone, sandstone, and limestone that were deposited in a variety of different environments such as flood plains, river systems, lakes, and shallow seas that existed during Medial and Late Paleozoic time (Figure 10). There are fossils of marine organisms and various terrestrial plants and animals.

Around mile marker 24, the gorge widens out, and the interstate climbs up onto a plateau. At exit 27, only a couple of miles before the Arizona/Utah border, geologically young black volcanic rocks can be seen forming a ridge top at a distance east of the highway (Black Rock Road exit). If you view the gorge from the Black Rock Road exit, you can see where the road starts to descend and enter the northern end of the gorge (Figure 4).

Just past that is the Arizona/Utah border where the scenic beauty of southern Utah becomes visible with a portion of the City of St. George ahead, Pine Valley Mountain, to the northwest, and in the distance the red cliffs of Navajo Sandstone around Zion Canyon National Park.

A final comment about Interstate 15

The construction cost for this section of highway in the late 1960s and 1970s was approximately $10 million per mile, or $49 million per mile in 2007 dollars. It was fully completed and opened in 1973 (Figure 11). At that time, it was the most expensive portion of the Interstate Highway System per mile. In the last few years, needed repairs and retrofitting of this portion of the interstate has occurred on an irregular basis, which sometimes makes the drive through the gorge even more entertaining.

Articles related to “Our Geological Wonderland: A trip through the Virgin River Gorge”

The famous inverted topography of basalt lava ridges of St. George

Thanks to Rick Miller for this series, and special thanks for this article on the Virgin River Gorge. Figure 5 is a virtual epiphany for me, explaining things I have seen and not understood.

Rick.

Your articles are an amazing addition to life in Ivins. The explanations you give are so well written. I finally know where the Colorado plateau and Great Basin meet! I love the geology of our region.

Is there a possibility of a trip through the gorge in a DSU bus (maybe through Road Scholar) with stops and mini lectures with you as the guide? As I read again your article on the gorge I wanted to be standing at those particular mile markers or on the overpasses. Going through at 65 mph doesn’t do it!

I’ve taken your class twice but there’s so much to learn that I still feel like a novice.

Many thanks for writing and sharing.

Peggy Lambert