Our Geological Wonderland: St. George has its faults

Faults and earthquakes in southern Utah

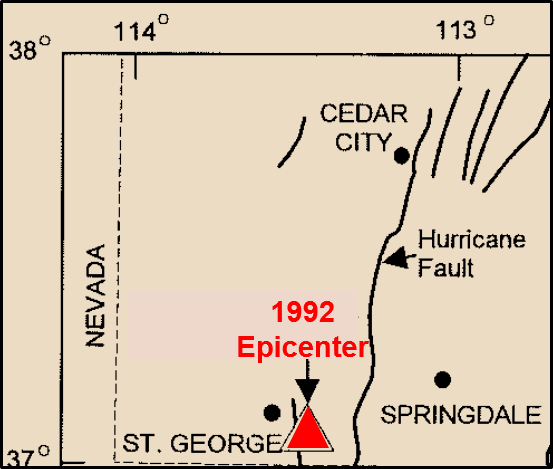

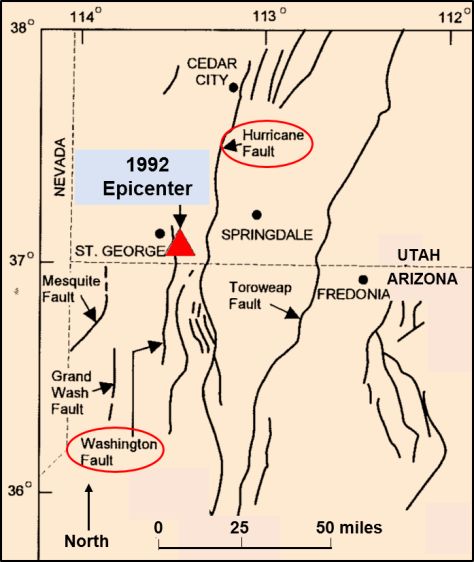

In the early morning hours of Sept. 2, 1992, St. George residents, all 29,000 or so of them, got a small taste of what happens in California. There was a significant earthquake with an epicenter very close to the city (Figure 1). This quake registered a magnitude of between 5.5 and 5.8 on the Richter scale and therefore was classified by seismologists as a “moderate” earthquake — kind of ho-hum by California standards but impressive by southern Utah standards. Some minor structural damage was reported along with some rock falls and landslides. There was no major damage, and there were no fatalities. So how come it happened here? (Optional answer: It’s not because so many retirees from California have moved here.)

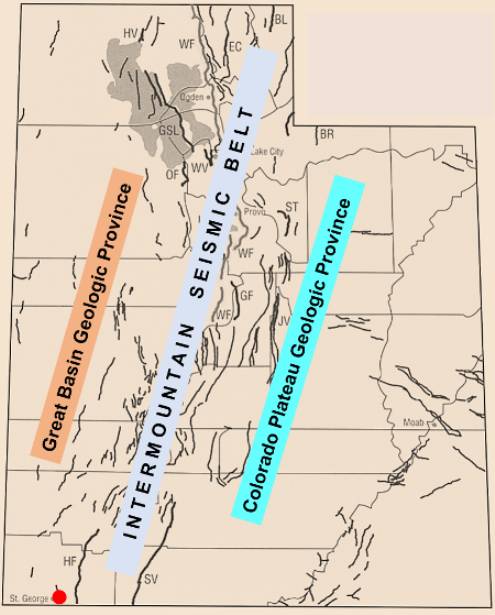

Well, as it turns out, like California, Utah has a lot of faults. Well, besides those faults, what I’m talking about are geological faults, the kind that are associated with earthquakes. There exist a relatively large number of such faults within the state, and as reported by the Utah Geological Survey and the United States Geological Survey, quite a few of those are potentially hazardous in the sense that they have in the past and could again cause significant earthquakes. A seismically active zone that extends diagonally through the state from the Arizona Strip up into Idaho is known as the Intermountain Seismic Belt (Figure 2). The location of this belt pretty much defines a boundary between geologic provinces of the Basin and Range to the west and the Colorado Plateau to the East.

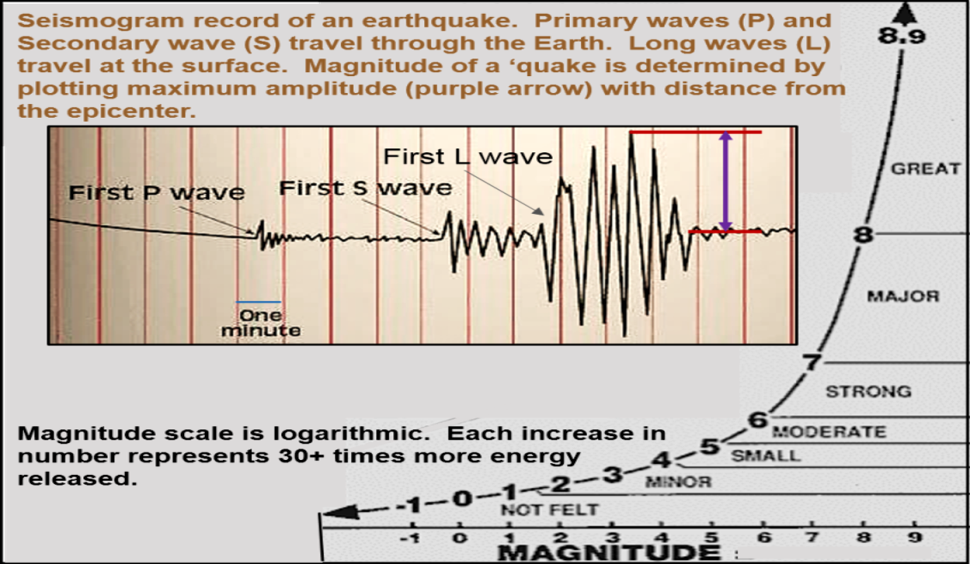

A geologic fault is the result of physical forces (stress) on rocks of the outer rock layers of Earth, which are known as the lithosphere. This stress can be in the form of compression, tension, or shear. When rocks break and shift position, an earthquake is generated, and a fault is formed. For over 100 years, earthquakes have been categorized on the basis of their size and energy (Figure 3).

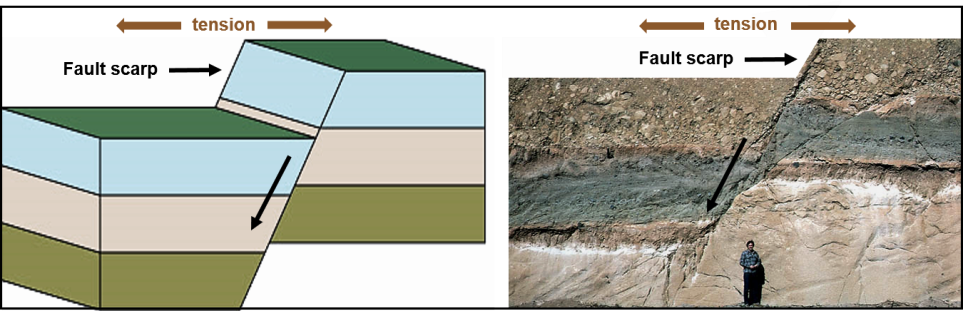

Geologists recognize a variety of different types of faults, which are named on the basis of how rocks shift relative to one another. The most common type of fault in Utah is known as a “normal fault” (Figure 4). Such a fault forms as a result of tension, or forces acting to pull apart rocks, kind of like a tug-of-war. When the rocks break, one side shifts downward relative to the other side.

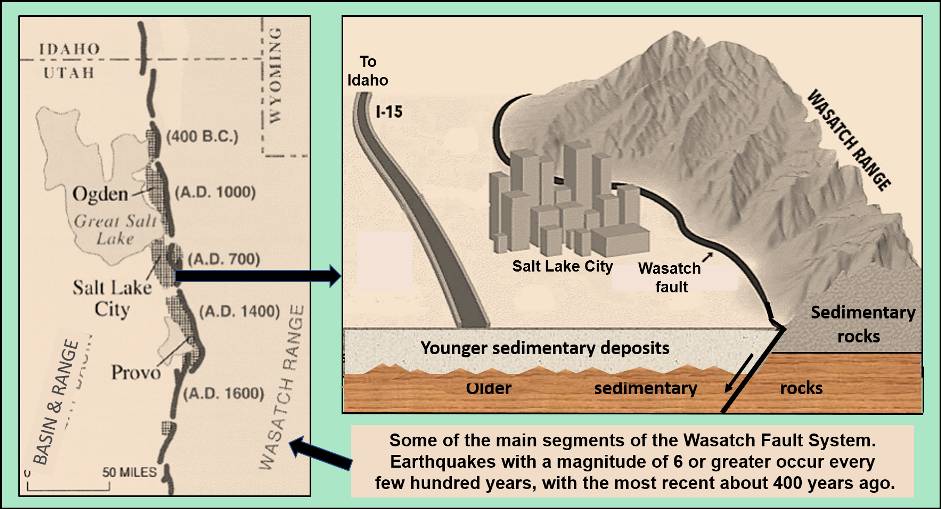

The central and northern portion of the seismic belt is more active and has more faults and earthquakes then the southern part. One major fault is well known as the Wasatch Fault, which is actually a number of fault segments that have been active for at least over 2.5 million years (Figures 5). Viewed from the Salt Lake Valley, the west side of the Wasatch Range shows a distinctive fault scarp and also how erosion has subsequently modified the scarp (Figure 6).

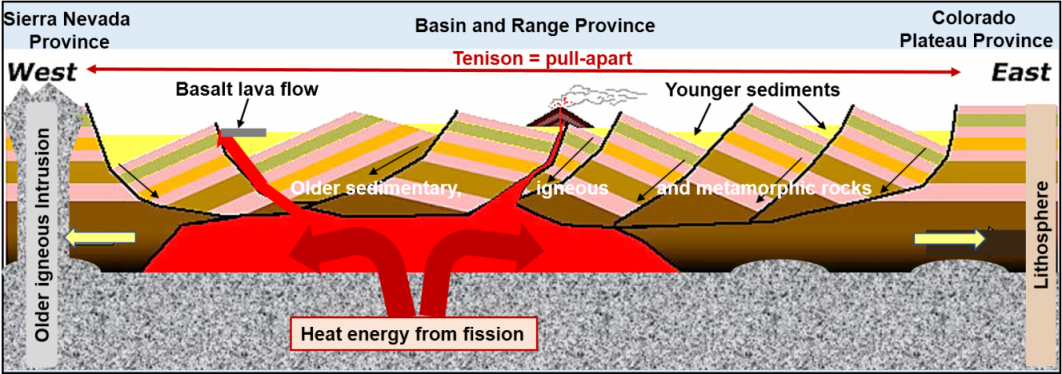

West of the Wasatch Range is the Basin and Range Province (Figure 7). This province represents a series of mostly north-trending mountain ranges separated by down-dropped valleys along normal faults. Because of tension pulling apart the rocks inn this area, the lithosphere has become thinner and faulted, allowing volcanic activity and hot spring (geothermal) areas to rise to the surface.

Faults and earthquakes in southern Utah

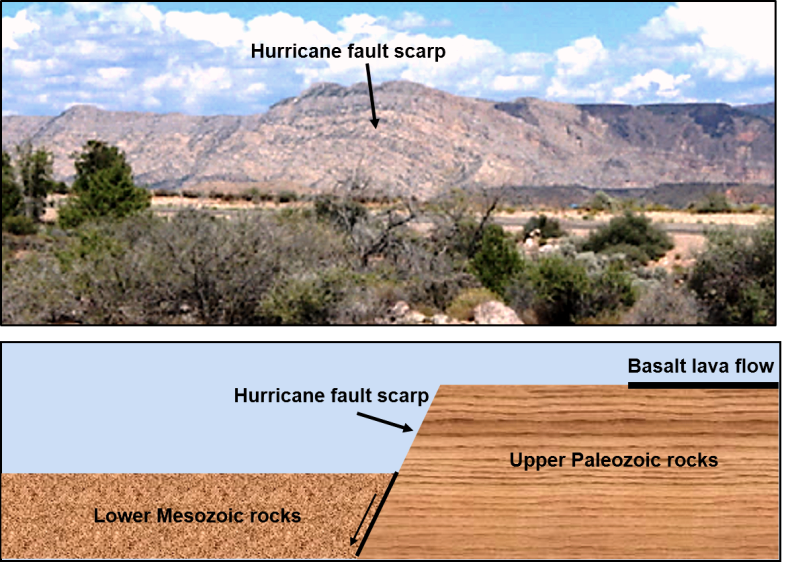

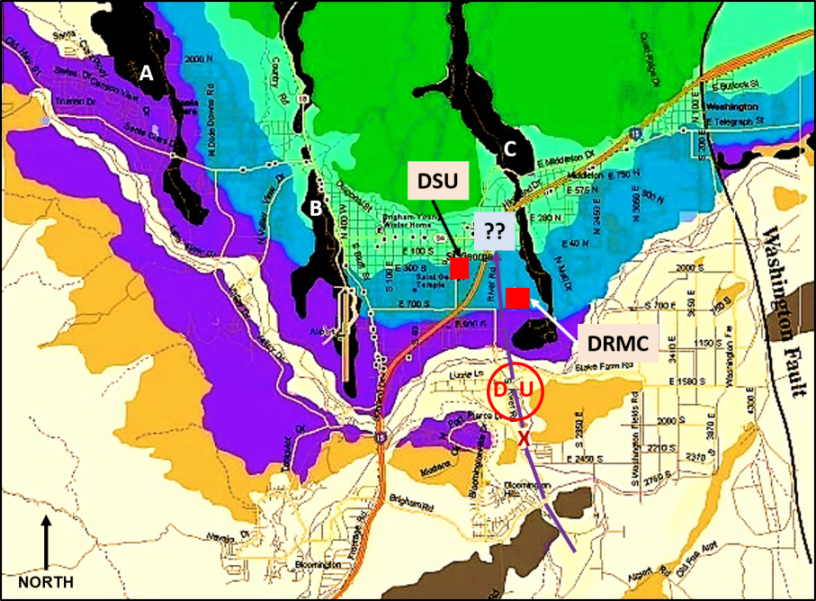

Of course, Washington County also has its faults (Figure 8). These faults represent the southern portion of the Intermountain Seismic Belt and represent a transition region between the Colorado Plateau Province to the east and the Basin and Range Province to the west. Two main mapped faults near St. George are the very long Hurricane Fault and the shorter Washington Fault, which runs through the city. The most distinctive is the Hurricane Fault, which is well exposed along the base of the Hurricane Cliffs (Figure 9). As indicated, it is a normal fault, and it can be traced from northern Arizona generally northward to just past Cedar City.

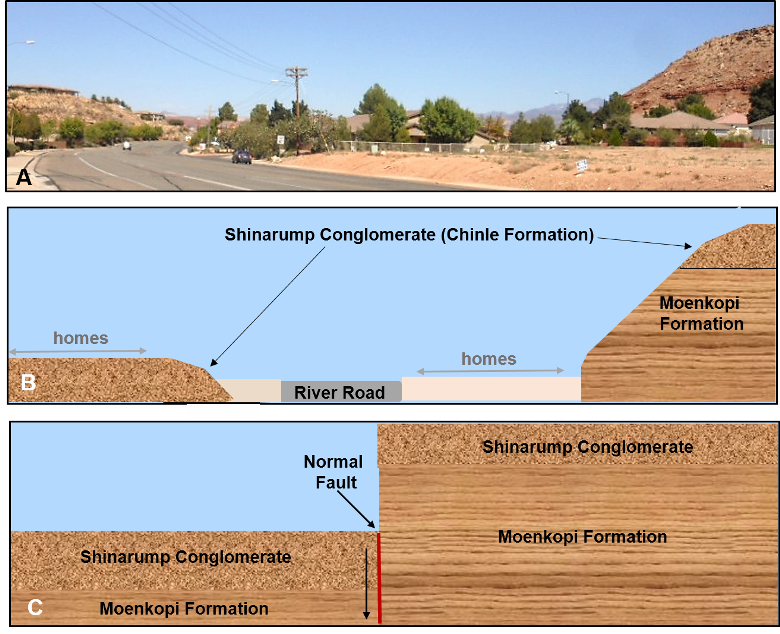

Two faults occur within St. George and Washington Cities (Figure 10). Distinct evidence of this fault can be seen on River Road, looking north from near the intersection with 2450 S, and it appears to also be a normal fault (Figure 11), but I do not have evidence from below the surface.

Be prepared

The Utah Geological Survey has published an earthquake preparedness report that provides very useful information, especially for the central and northeastern parts of Utah. These areas, which are within the Intermountain Seismic Belt and especially in close proximity to the Wasatch Fault system, are more likely to experience a large-scale earthquake than the southern part of Utah. Recently published estimates from the USGS (2016) suggest about a 43 percent chance of a magnitude 6.5 or greater earthquake along the Wasatch Fault within the next 50 years. This estimate is based on detailed studies of the recurrence history along various segments of the fault. The Utah Geological Survey has also prepared some publications on this topic, including tips on earthquake preparedness, which can be accessed online here and here.

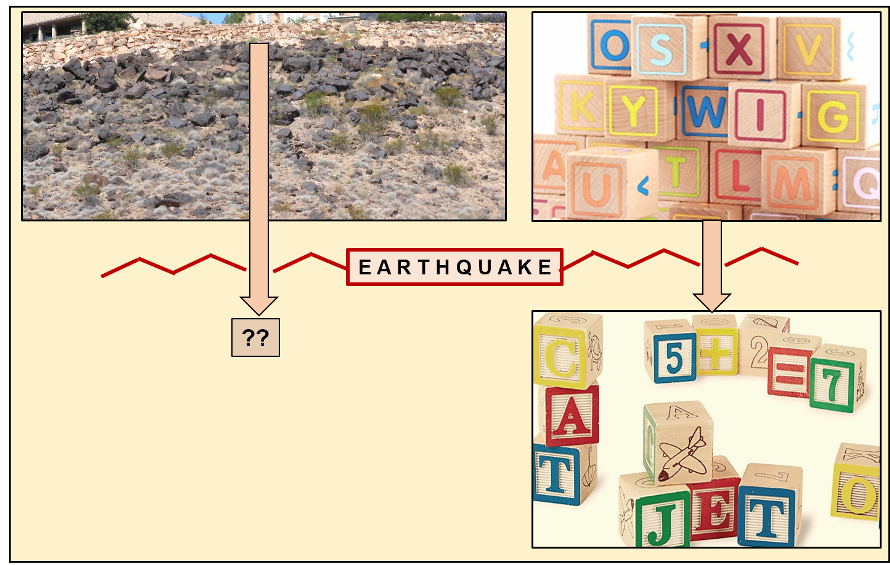

The structural faults in the St. George area have been active in the past and are also likely to generate an earthquake in the future. However, it is much less likely that any of them will generate a strong or a major earthquake with a magnitude greater than 6 as is likely in the northern part of the state. Nonetheless, considering the significant increase in population and various hilltop “scenic” building sites that have been developed since 1992, even a moderate quake will create damage, particularly rock falls and landslides (Figure 12). Roads, homes, and other structures built on blue clay and other unstable soils are likely to suffer some damage.

Articles related to “Our Geological Wonderland: St. George has its faults”

Our Geological Wonderland: Quail Lake and the Virgin Anticline

Our Geological Wonderland: Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm