Our Geological Wonderland: Geologic hazards in St. George and southern Utah

Living within Washington County and the city of St. George in southern Utah, we are blessed with the occurrence and potential occurrence of at least four different and sometimes deadly natural disasters, which are commonly referred to as geologic hazards. These hazards include flooding, mass movements such as landslides and rock falls, volcanic activity, and earthquakes.

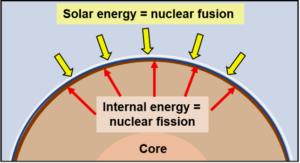

Most people think of natural disasters as events like major hurricanes, catastrophic earthquakes, or lethal volcanic eruptions. These events and others are part of how the Earth functions and are the result of the interplay of two major sources of energy: solar energy from the Sun — nuclear fusion — and heat energy generated within the Earth — nuclear fission (Figure 1).

Hazards that result from the input of solar energy — fusion

Floods

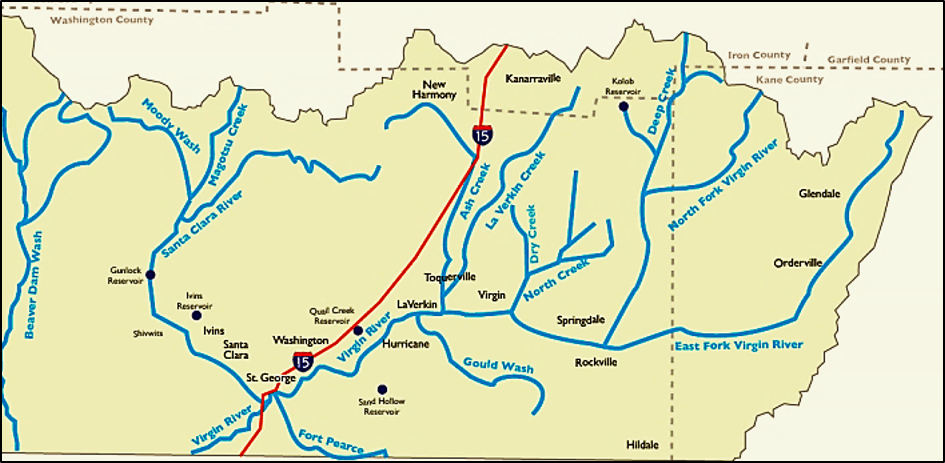

We think of Washington County and surrounding areas as a desert environment. Yet we have a few year-round flowing rivers, two of which flow through the St. George area. They are the Virgin and Santa Clara Rivers, and every so often during significant storms, they reach flood stage. These rivers are part of a regional drainage system, a drainage basin, which eventually flows into the Colorado River at Lake Mead northeast of Las Vegas (Figure 2).

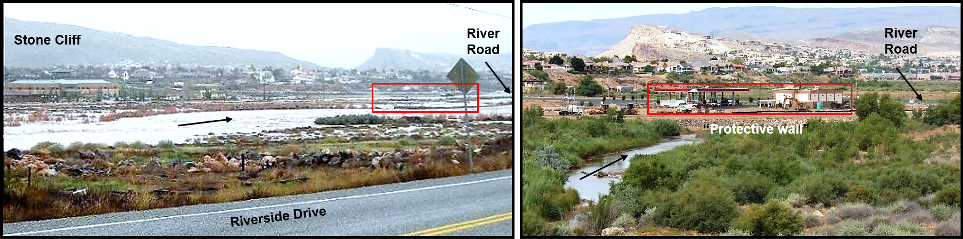

In Washington County and the city of St. George, these two rivers are the main channels draining water from rainstorms and melting snow. When the amount of water entering the system is greater than can be carried in these channels, such as during a major storm, the water overflows its banks and spreads out over land areas within areas appropriately termed “floodplains.” Thus, there are two situations in which a river can become hazardous. First is the possibility of erosion of the riverbanks themselves (Figure 3). Second is the possible flooding of the floodplain area (Figure 4).

A readily observable flood plain can be seen extending from the south end of Foremaster (Middleton) Ridge to the base of Stone Cliff (Figure 4). As this example indicates, floodplains are generally nearly flat, lowland areas and are therefore relatively easy to develop and build structures. This tends to attract developers. When looking to rent, buy, or build a home or business, it is therefore important to consider whether the property is at the edge of a river channel or located within a floodplain.

Flooding of the Virgin River has played havoc periodically with human occupation in southwestern Utah ever since the first settlers arrived in 1861 and began to grow cotton. Can we expect further floods? The answer is yes, without a doubt. Can we determine when? The answer is no.

Mass movements

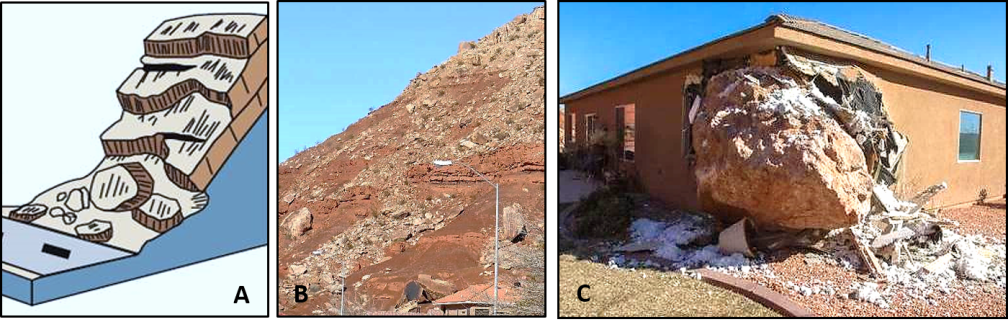

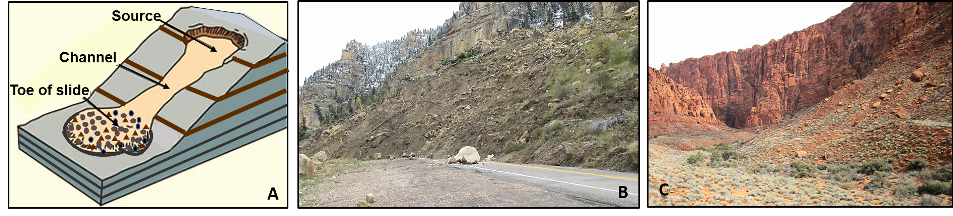

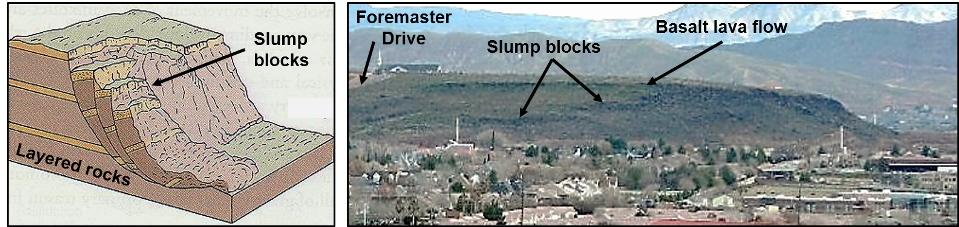

Although given a somewhat fancy name, mass movements in a geologic sense are essentially downslope movement of soil, rocks, and human structures. In the St. George area, we have concerns about rock falls, landslides, slumps, and soil flow (Figure 5). These hazards occur because we have topographic highs, potentially weak rocks and soils, and of course gravity. In contrast, areas such as Iowa are not likely to have much in the way of mass movements because they are topographically nearly flat.

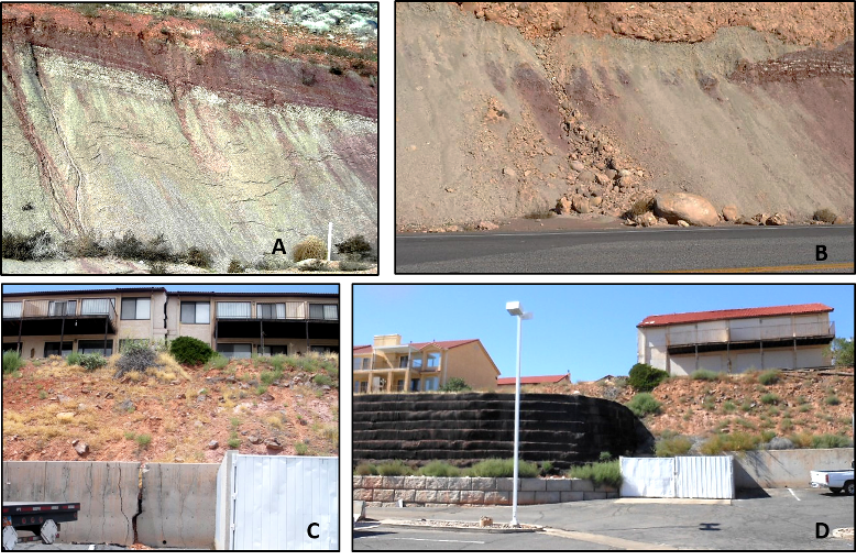

Making things out of clay in a ceramics class is fun and creative. In contrast, “don’t build on blue clay” is a common phrase heard in St. George. And for good reason as this particular clay is unstable and the cause of a number of slumps and slides that have damaged or destroyed roads and buildings around the city and adjoining areas (Figure 6). From a geologic perspective, our blue clay has an interesting history that extends back in geologic time to the Triassic Period a little over 200 million years ago. This clay primarily occurs within the upper member of the Chinle Formation. This member, known as the Petrified Forest Member, received its name from exposures at Petrified Forest National Park in northern Arizona.

Hazards that result from the input of internal energy — fission, radioactive decay

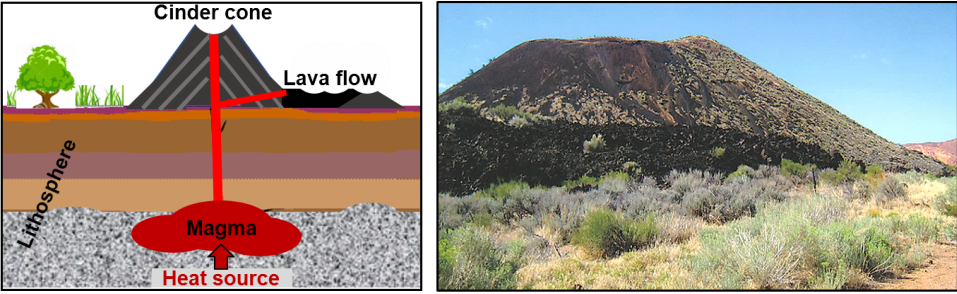

Volcanic eruptions

Along with other areas of southern Utah, northern Arizona, and southern Nevada, Washington County has been a region of significant volcanic activity for over 30 million years. The most recent activity has been eruptions of lava and formation of cinder cones. These volcanic features form abundant and distinctive features in this area (Figure7). Although there is still a source of heat below the surface as indicated by hot springs in the area, current assessment by the Geological Survey indicates a very low probability of an eruption in the near future.

Earthquakes

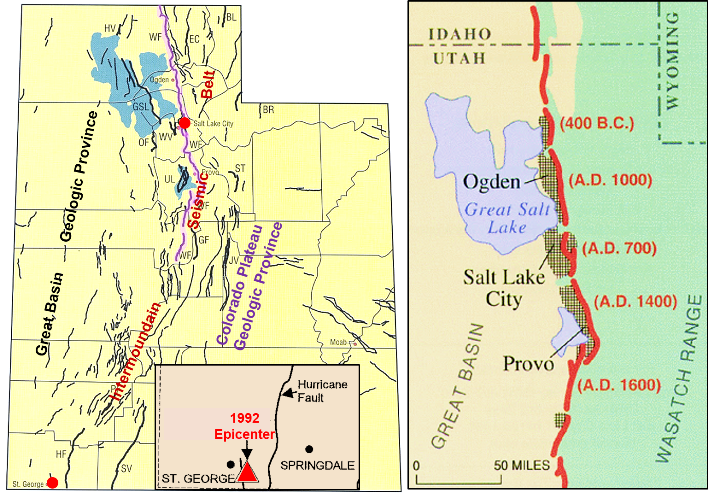

Utah is neatly bisected by numerous faults that form what is known as the Intermountain Seismic Belt (Figure 8). This belt trends northeastward from the southwestern part of the state up into Idaho. It is a region of numerous earthquakes, most of which are relatively small. But occasionally, a larger one occurs. The most recent significant earthquake in the St. George area occurred in 1992 and registered a magnitude of 5.5–5.8 on the old Richter scale. General consensus by the Utah Geologic Survey is that there is a low probability of a large quake in the southern part of the state. Farther north, around Salt Lake City, there could be a strong earthquake within this century.

Other “self-induced” geologic hazards

Some geologic hazards, which may have a low probability of occurring, are frequently exacerbated by human activities — for example, building on an unstable slope or at the base of a slope where there have been previous rock falls or landslides, building on blue clay, or building in a flood zone. In some of these conditions, there is little likelihood of a geologic hazard until one is actually created by construction. One example is provided by the history of the Quail Creek Reservoir and Dam, which was completed in 1985, failed on New Year’s Day in 1989, and created a large but temporary flood along the Virgin River (Figure 9).

A second example is provided by the runway at the St. George Municipal Airport, which was completed in 2011. The runway is scheduled for a complete rebuild, which will require closing the airport from May through August 2019. The problem is the result of original construction on expandable blue clay, lack of deep enough excavation for the runway bed, and lack of installation of barriers to prevent water from seeping into the clay layers below the runway surface (Figure 10).

A third example occurred in Rockville in December 2013 and resulted in the total destruction of a home and the death of the two occupants from a very large rock. Apparent from the following images is the hazardous location of the destroyed home as well as other homes in close proximity (Figure 11). This is an example of poor decision making. Based on the geologic evidence of numerous large rock falls, these homes and others not in the picture are pretty much like bowling pins waiting to be knocked down.

Looking on the positive side, we don’t have hurricanes, tornadoes, major blizzards, or tsunamis. Geologic hazard maps of the St. George area can be accessed here.

Fascinating information. Thank you for publishing!

Unknown is a very scary thing, but not for us. We are one of many families who simply fell in love with the landscape in this area and determined to move to St. George, Utah. We’ve done a lot of research from Utah Government Websites and many articles like yours. Thank you for publishing your knowledge and expertise that re-enforce our decision of where we want to relocated ourselves and to enjoy our lives in such a beautiful City.

Great article. Interesting and informative.